16 May 2023: Original Paper

Breaking Antimicrobial Resistance: High-Dose Amoxicillin with Clavulanic Acid for Urinary Tract Infections Due to Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing

Piotr Wilkowski1ABCDEF, Ewa HryniewieckaDOI: 10.12659/AOT.939258

Ann Transplant 2023; 28:e939258

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Carbapenems are the primary treatment for urinary tract infections (UTIs) caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. However, the recurrence rate is high, and patients often require rehospitalization. We present the results of an observational study on patients with recurrent UTIs who were treated in an outpatient setting with maximal therapeutic oral doses of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid.

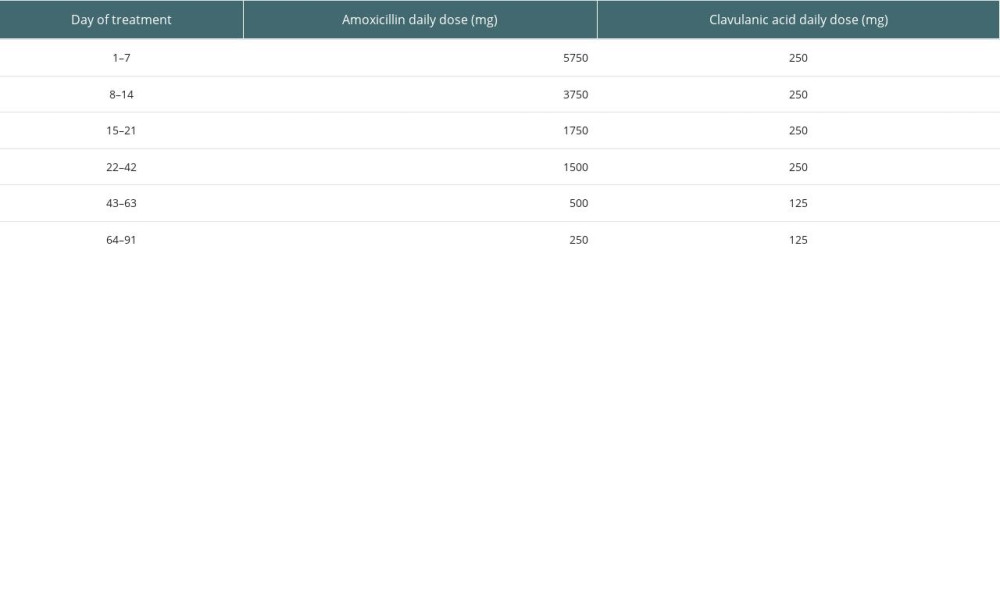

MATERIAL AND METHODS: All patients had pyuria and ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in urine culture. The starting dosage was 2875 g of amoxicillin twice daily and 125 mg of clavulanic acid twice daily. We down-titrated the doses every 7-14 days and continued prophylactic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid at 250/125 mg for up to 3 months. We defined therapeutic failure as ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae in urine culture during therapy and recurrence as positive urine culture with the same strain within 1 month after the end of treatment.

RESULTS: We included 9 patients: 7 kidney graft recipients, 1 liver graft recipient, and 1 patient with chronic kidney disease. We observed no therapeutic failures and no recurrences in the study group during the study period. In 1 case, the patient experienced a subsequent UTI caused by ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae 4 months after completing the therapy.

CONCLUSIONS: In conclusion, it is possible to break the resistance of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains with high doses of oral amoxicillin with clavulanic acid. Such treatment could be an alternative to carbapenems in select cases.

Keywords: Amoxicillin, beta-Lactamases, Clavulanic Acid, Kidney Transplantation, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Urinary Tract Infections, Humans, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Klebsiella Infections, Microbial Sensitivity Tests, Drug Resistance, Bacterial, Carbapenems

Background

Infections with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains are a growing therapeutic problem worldwide [1,2]. The spread of these bacteria makes it a significant etiological factor for urinary tract infections (UTIs) among patients after kidney transplantation [3]. UTIs caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae are diagnosed in approximately 10% of kidney graft recipients within the first year after transplantation [3]. They are among the most important risk factors for poor kidney graft survival [4,5]. ESBL-producing

This report presents the treatment results with maximal therapeutic oral doses of amoxicillin combined with average doses of clavulanic acid in a cohort of patients with UTIs caused by ESBL-producing

Material and Methods

This observational cohort study included patients with UTIs caused by ESBL-producing

Results

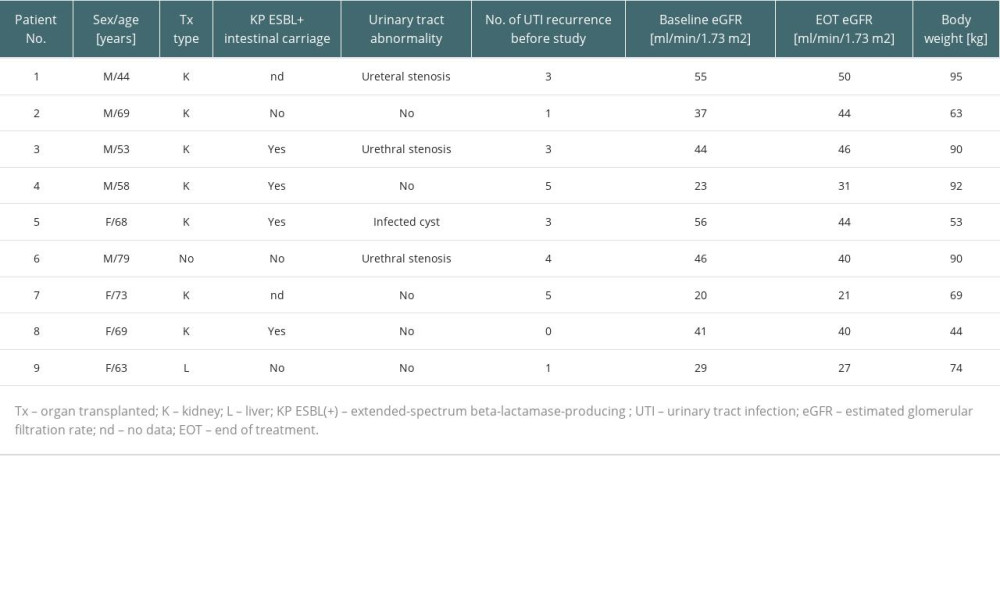

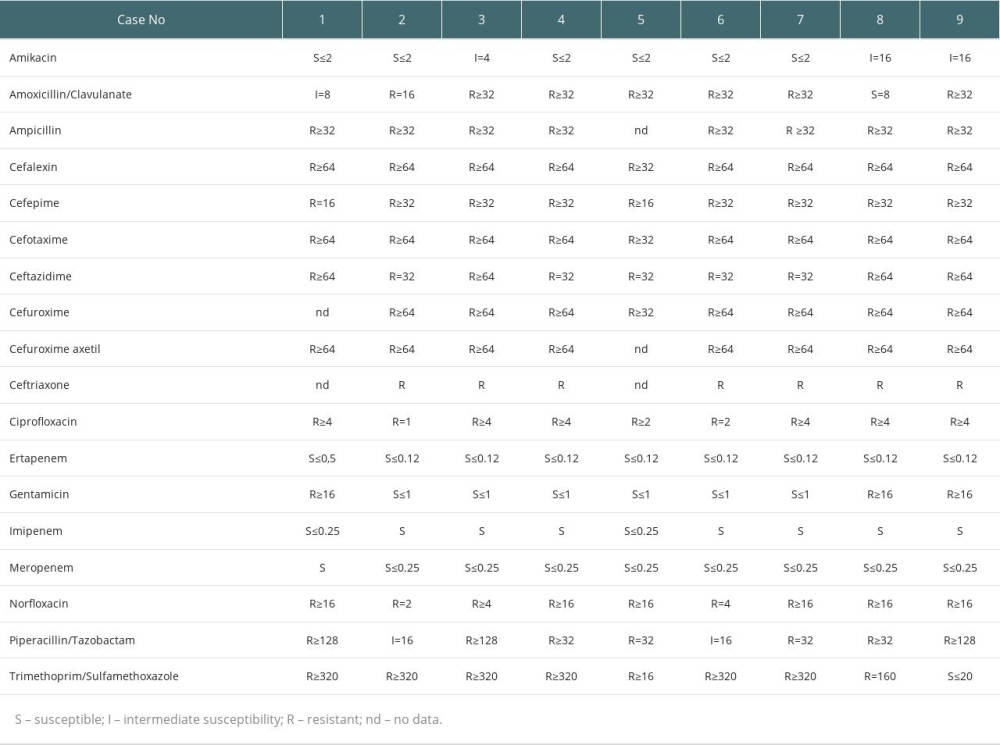

The study included 9 patients (4 women, 5 men), including 7 kidney graft recipients, 1 liver graft recipient, and 1 patient with chronic kidney disease. Seven patients had a previous history of UTIs caused by ESBL-producing

Table 3 shows the urine culture results. The UTI symptoms of all patients resolved within the first week of therapy. The urine cultures became negative after 7 days and remained negative for all patients throughout the treatment period and 1-month follow-up period, during which we observed no recurrence of the infection. All patients were followed-up for 6 months after the antibiotic therapy. In 1 case, the patient experienced a subsequent UTI caused by ESBL-producing

Discussion

Our study showed that prolonged therapy with large starting doses of oral amoxicillin with clavulanic acid is a highly effective and safe alternative therapy for cases of UTIs caused by ESBL-producing

Oral fosfomycin might also be a successful treatment for UTIs caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria in kidney transplant recipients. In a multicenter study from Spain, therapy with oral fosfomycin resulted in microbiological cure in 70% of cases 1 month after the therapy. However, only 14% of the isolates were ESBL-producing bacteria [15]. Moreover, oral fosfomycin is not recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing to treat complicated UTIs. Most of our patients were kidney transplant recipients with urinary tract abnormalities.

A group from Spain recently published a multicenter study showing that therapy with beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors is as effective as carbapenem-based therapy in bacteremia secondary to UTI in kidney transplant recipients. However, these results are only applicable to piperacillin-tazobactam because only 2 patients in the study group underwent therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid [16]. Amoxicillin, like most penicillins, can be used in large doses without significantly increasing the risk of adverse effects. The use of large doses of amoxicillin in treating otitis media was not associated with more frequent adverse effects, including diarrhea, compared with standard doses [17]. The results of a prospective study with 51 pediatric patients at a poison control center suggest that doses smaller than 250 mg/kg of amoxicillin are not associated with significant clinical symptoms [10]. Large doses of amoxicillin are effective in treating drug-resistant strains of pneumococcal carriage and community-acquired pneumonia and even as dual therapy with esomeprazole to eradicate

There has also been concern that conventional doses of beta-lactams might not always achieve adequate pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic indices [18]. Dose adjustment is necessary for chronic kidney disease with an eGFR <30 mL/min. Patients should maintain adequate fluid intake and urinary output to reduce the possibility of amoxicillin crystalluria. Cases of hepatoxicity with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid have been reported, but these were attributed to the adverse effects of the beta-lactamase inhibitor and not to the antibiotic itself [19]. Amoxicillin is well tolerated; the maximal recommended therapeutic dose is 6.0 g/day in adults and children with body weight ≥40 kg and 3.0 g/day in subjects with body weight <40 kg. The maximal recommended therapeutic dose in this subgroup is 100 mg/kg body weight/day.

Overuse of carbapenems has led to a growing problem of increasing numbers of carbapenem-resistant

The long-term use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in prophylactic doses in our study might be controversial due to the previously observed recurrence of infection despite 2–3 weeks of therapy with intravenous antibiotics, which might indicate this bacterium’s extensive ability to survive despite the use of potentially effective therapy. The high recurrence rate in kidney transplant patients might be caused by immunosuppressive therapy and concomitant urinary outflow disorders resulting from the kidney graft itself [23]. However, it appears that certain properties of

In recent years, an increase has been observed in the frequency of infections caused by hypervirulent strains of K.

Our study has certain limitations, given that we studied a small group of patients and that a control group was not included. An additional limitation is the lack of data on the sensitivity of

Conclusions

It is possible to break the resistance of ESBL-producing

References

1. Chong Y, Shimonda S, Shimono N: Infect Genet Evol, 2018; 61; 185-88

2. Padmini N, Ajilda AAK, Sivakumar N, Selvakumar G: J Basic Microbiol, 2017; 57; 460-70

3. Alevizakos M, Nasioudis D, Mylonakis E, Urinary tract infections caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in renal transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Transpl Infect Dis, 2017; 19; e12759

4. Fiorentino M, Pesce F, Schena A, Updates on urinary tract infections in kidney transplantation: J Nephrol, 2019; 32; 751-61

5. Ooms L, IJzermans J, Voor In ‘t Holt A, Urinary tract infections after kidney transplantation: A risk factor analysis of 417 patients: Ann Transplant, 2017; 22; 402-8

6. Rodríguez-Baño J, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Machuca I, Pascual A, Treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-, ampC-, and carbapenemase-producing Treatment of Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-, AmpC-, and Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Clin Microbiol Rev, 2018; 31; e00079-e00117

7. Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Rodríguez-Baño J, Current options for the treatment of infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in different groups of patients: Clin Microbiol Infect, 2019; 25; 932-42

8. Bodro M, Sabé N, Tubau F, Risk factors and outcomes of bacteremia caused by drug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens in solid-organ transplant recipients: Transplantation, 2013; 96; 843-49

9. Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis: Lancet Infect Dis, 2018; 18; 318-27

10. Rajapakse NS, Vayalumkal JV, Vanderkooi OG, Time to reconsider routine high-dose amoxicillin for community-acquired pneumonia in all Canadian children: Paediatr Child Health, 2016; 2; 65-66

11. Zullo A, Ridola L, De Francesco V, High-doses omeprazole and amoxicillin dual therapy for first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication: A proof of concept study: Ann Gastroenterol, 2015; 28; 448-51

12. Swanson-Biearman B, Dean BS, Lopez G, Krenzelok EP, The effects of penicillin and cephalosporin ingestions in children less than six years of age: Vet Hum Toxicol, 1988; 30; 66-67

13. Pilmis B, Scemla A, Join-Lambert O, ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae-related urinary tract infections in kidney transplant recipients: Incidence and risk factors for recurrence: Infect Dis (Lond), 2015; 47; 714-18

14. Pouch S, Kubin CJ, Satlin MJ: Transpl Infect Dis, 2015; 17; 800-9

15. López-Medrano F, Silva JT, Fernández-Ruiz M, Oral fosfomycin for the treatment of lower urinary tract infections among kidney transplant recipients – results of a Spanish multicenter cohort: Am J Transplant, 2020; 20; 451-62

16. Pierrotti LC, Pérez-Nadales E, Fernández-Ruiz M, Efficacy of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors to treat extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection in kidney transplant recipients (INCREMENT-SOT Project): Transpl Infect Dis, 2021; 23; e13520

17. Lahiry S, Dalal K, Pawar A, Kotak B, High-dose amoxicillin supported with clavulanic acid as empirical therapy in acute otitis media: Asian J Med Sci, 2021; 12; 134-44

18. Harris PN, Tambyah PA, Paterson DL, β-lactam and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae: Time for a reappraisal in the era of few antibiotic options?: Lancet Infect Dis, 2015; 15; 475-85

19. deLemos A, Ghabril M, Rockey DC, Drug-induced liver injury network (DILIN). amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced liver injury: Dig Dis Sci, 2016; 61; 2406-16

20. Tamma PD, Rodriguez-Baňo J, The use of noncarbapenem β-lactams for the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase infections: Clin Infect Dis, 2017; 64; 972-80

21. Ding Y, Wang H, Pu S: Infect Drug Resist, 2021; 14; 475-81

22. Kachalov VN, Nguyen H, Balakrishna S: PLoS Comput Biol, 2021; 17; e1008446

23. Ariza-Heredia EJ, Beam EN, Lesnick TG, Urinary tract infections in kidney transplant recipients: Role of gender, urologic abnormalities, and antimicrobial prophylaxis: Ann Transplant, 2013; 18; 195-204

24. Prokesch BC, TeKippe M, Kim J: Lancet Infect Dis, 2016; 16; e190-95

25. Paczosa MK, Mecsas J: Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 2016; 80; 629-61

26. Lee CR, Lee JH, Park KS: Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2017; 7; 483

27. Gorrie CL, Mirčeta M, Wick RR: Clin Infect Dis, 2017; 65; 208-15

In Press

15 Mar 2024 : Review article

Approaches and Challenges in the Current Management of Cytomegalovirus in Transplant Recipients: Highlighti...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.941185

18 Mar 2024 : Original article

Does Antibiotic Use Increase the Risk of Post-Transplantation Diabetes Mellitus? A Retrospective Study of R...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943282

20 Mar 2024 : Original article

Transplant Nephrectomy: A Comparative Study of Timing and Techniques in a Single InstitutionAnn Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942252

28 Mar 2024 : Original article

Association Between FEV₁ Decline Rate and Mortality in Long-Term Follow-Up of a 21-Patient Pilot Clinical T...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942823

Most Viewed Current Articles

05 Apr 2022 : Original article

Impact of Statins on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Living-Donor Liver TransplantationDOI :10.12659/AOT.935604

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935604

12 Jan 2022 : Original article

Risk Factors for Developing BK Virus-Associated Nephropathy: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study of ...DOI :10.12659/AOT.934738

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e934738

22 Nov 2022 : Original article

Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipient...DOI :10.12659/AOT.937988

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e937988

15 Mar 2022 : Case report

Combined Liver, Pancreas-Duodenum, and Kidney Transplantation for Patients with Hepatitis B Cirrhosis, Urem...DOI :10.12659/AOT.935860

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935860