15 February 2022: Original Paper

Carbohydrate Metabolism Disorders in Relation to Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy (CAV) Intensification in Heart Transplant Patients According to the Grading Scheme Developed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT)

Katarzyna Zielińska1ABCDEF*, Leszek KukulskiDOI: 10.12659/AOT.933420

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e933420

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) is the leading complication limiting the long-term survival of heart transplant (HTx) patients. The goal of this study was to assess carbohydrate metabolism disorders in relation to CAV intensification in heart transplant patients according to the ISHLT grading scheme.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: This retrospective study involved 477 HTx recipients undergoing angiographic observation for up to 20 years after transplantation. The patients were assigned to 4 groups on the basis of their carbohydrate metabolism status: without diabetes, with type 2 diabetes prior to HTx, with new-onset diabetes after transplantation, and with transient hyperglycemia.

RESULTS: In the study, 62.7% (n=299) of the patients manifested no diabetes after HTx, while 14.3% (n=68) of patients had type II diabetes prior to HTx and 18.4% (n=88) developed new-onset diabetes after transplantation. In total, 1442 coronary angiograms were taken in the specified control periods. CAV incidence increased over time after transplantation, reaching 11% after 1 year, 57% after 10 years, and 50% after 20 years. The longest survival time was observed for patients who had developed type II diabetes prior to HTx, but the difference was not statistically significant. The multivariate analysis failed to identify an independent risk factor for developing cardiac allograft vasculopathy.

CONCLUSIONS: Despite the relatively high rates of CAV and carbohydrate metabolism disorders in heart transplant patients, our retrospective analysis revealed no statistically significant link between these 2 diseases.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Metabolism, Diabetes Complications, Heart Transplantation, Allografts, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2, Humans, Lung Transplantation

Background

The second half of the 20th century was a time of major developments in transplant medicine. With the advancement in surgical procedures, the new challenge was to overcome the immune response of the recipient’s body. Effective immunosuppressive protocols were developed as a result of many years of observations and research, which significantly improved postoperative care. However, the incidence of long-term complications, such as cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) and post-transplantation diabetes mellitus (PTDM), must be reduced further as much as possible to increase patients’ life expectancy and quality of life [1,2].

The carbohydrate metabolism disorders, such as post-transplantation diabetes mellitus (PTDM), are a major issue, not only after heart transplantation (HTx), but also after other solid organ transplantations. It occurs in 10% to 20% of kidney transplant recipients [3]. It is well established that PTDM and carbohydrate metabolic disorders are associated with increased mortality due to cardiovascular events [3–6].

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is one of the 3 most common causes of death, together with cancer and renal failure, in the first 3 years following transplantation [7]. The development of vasculopathy after transplantation is a complex process. It is primarily influenced by immunologic factors, such as the infiltration of the vascular intima by inflammatory cell populations, including lymphocytes and macrophages. The significance of specific antibodies produced by activated B lymphocytes is emphasized as well [8–10]. It is believed that commonly known risk factors for atherosclerosis have a major role in the development of the disease in extended time periods. This results in overlap of typical atherosclerosis with vasculopathic lesions.

The risk factors for CAV development identified thus far include donor age of over 50 years, dyslipidemia in the recipient, nicotinism, type II diabetes, episodes of acute cellular rejection, and donor-specific antibodies binding to human leukocyte antigens. Statins and mTOR kinase inhibitors reduce the risk of onset of cardiac allograft vasculopathy [11–18].

CAV may result in arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death, since typical stenocardial problems do not occur because of cardiac denervation. This is why it is so essential to perform routine recommended coronary angiography, which is the criterion standard in CAV diagnostics according to the current ISHLT guidelines of 2010 [19].

It is recommended to perform angiography once a year or every 2 years. Less frequent monitoring can be performed in patients with no abnormalities found over a period of 3–5 years [20]. However, angiography-based CAV diagnosis can be extremely difficult due to the diffuse and distal location of concentric stenoses in CAV, which is unlike the focal and eccentric proliferation in coronary artery disease.

The goal of this study was to measure the incidence and determine the risk factors for cardiac allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant patients, and to analyze their long-term outcomes depending on the occurrence of carbohydrate metabolism disorders.

Material and Methods

SAMPLE GROUP:

The analysis encompassed 477 patients hospitalized at the Severe Circulatory and Respiratory Insufficiency and Mechanical Circulatory Support Ward of the Silesian Center for Heart Diseases in Zabrze, who had undergone heart transplantation and coronary angiography during observation in the years 2001–2018. The patients were divided into 4 groups: patients without diagnosed diabetes, patients with type II diabetes diagnosed prior to transplantation, patients with transient hyperglycemia, and patients with diabetes after transplantation.

Diabetes mellitus was classified according to the guidelines created by the WHO. Temporary hyperglycemia in the early post-transplant period was identified as a significant clinical problem; however, due to the lack of clear diagnostic criteria, these data were not analyzed.

Different publications have their own, varied definitions of post-transplant diabetes. We have adopted the principle that each new diagnosis of diabetes following heart transplantation is defined as NODAT.

“New-Onset Diabetes After Transplantation” (NODAT) refers to patients whose diabetes was only diagnosed after organ transplantation (this term does not refer to hyperglycemia found shortly after the procedure) [21].

Post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM) includes patients with persistent hyperglycemia (possibly due to pre-existing diabetes that had not been diagnosed before transplantation), NODAT patients, and those with temporary post-transplant hyperglycemia that resolves within 1 year of transplantation [22].

The CAV grading was based on angiocardiography, according to the criteria proposed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). The cardiac angiography results were analyzed and ISHLT CAV grades were given retrospectively. The need for revascularization resulted in the highest grade. The institutional follow-up protocol consisted of angiocardiography performed 15 months after transplantation (when there were no other indications). When coronary artery disease was observed during the exam, angiography was done every 1–2 years. However, when percutaneous coronary intervention was performed, the controlled catheterization was scheduled after 6 months.

The nature of the lesions largely suggests their type: donor-transferred ones are short, eccentric, and occur in large vessels. In our study, CAV classification was developed based on the result of the first coronary angiography.

DATABASE:

A retrospective study was carried out by analyzing the patient database. The database included the following clinical parameters from the discharge report, concerning the donor: sex, age, cause of death; and the recipient: sex, age, body mass, height, clinical diagnoses, treatment, presence of diabetes, arterial hypertension, renal failure, and cytomegalovirus infection (CMV)- patients with IgG- and IgM-positive results of serology tests. The database also contained information regarding NODAT treatment and occurrence of acute graft rejection (date of rejection control, rejection grade per ISHLT, rejection treatment). Additionally, it also included data concerning coronary vessel angiograms, which made it possible to classify them according to the CAV categories defined by ISHLT.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

For quantitative variables, the data are presented as average values±standard deviation, whereas qualitative variables are presented in the form of numbers and percentages. Data regarding the time until the occurrence of an event (patient death) was visualized by means of the Kaplan-Meier method; the occurrence of differences between the studied groups was determined by means of the χ2 test.

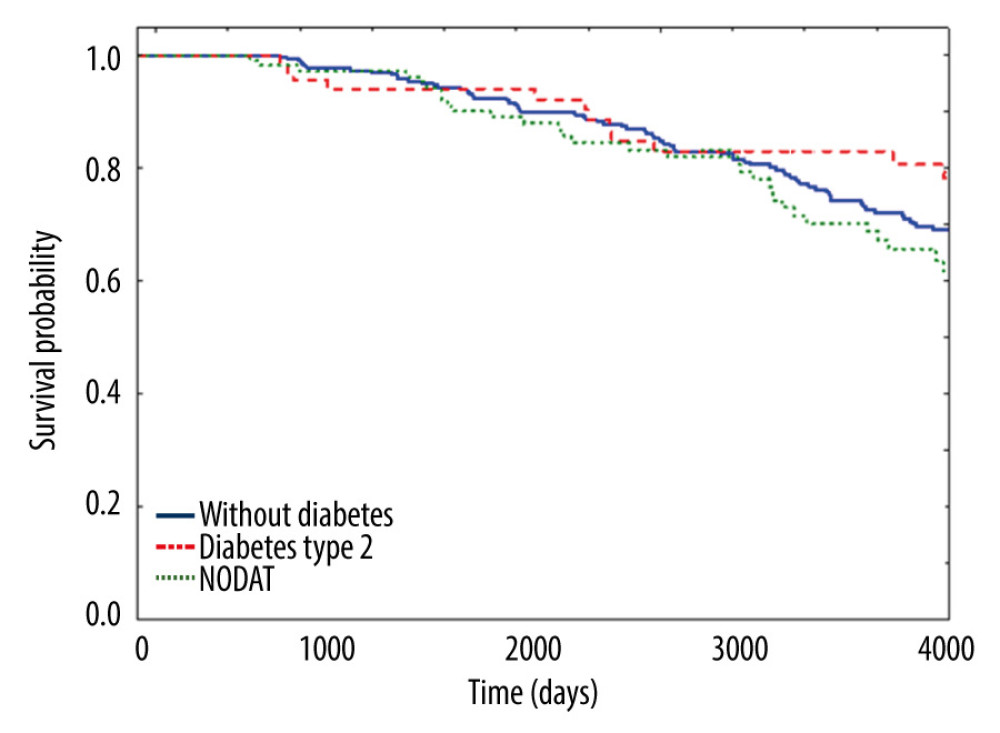

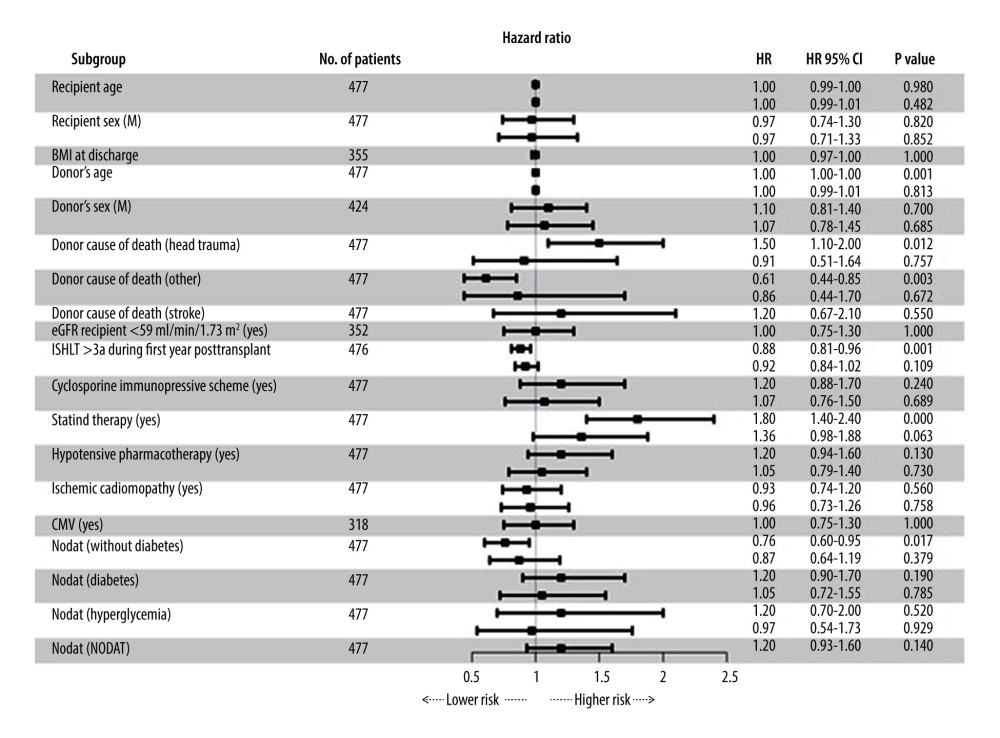

The results of the survival and risk analysis were presented using Cox proportional-hazards models. A univariate analysis was performed for all the risk factors. The multivariate model only contains variables with a sufficient number of observations. For risk factors with 2 types of regression, univariate and uncorrected HR values are presented above, whereas corrected HR values with multiple variables can be found below. In the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, the CAV grades were evaluated as variables dependent on time and adapted to the date of transplantation, the age and the sex of the recipient, the incidence of ischemic cardiomyopathy prior to transplantation, arterial hypertension, and the estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The global level of significance in the conducted analysis was defined as

Results

GROUP CHARACTERISTICS:

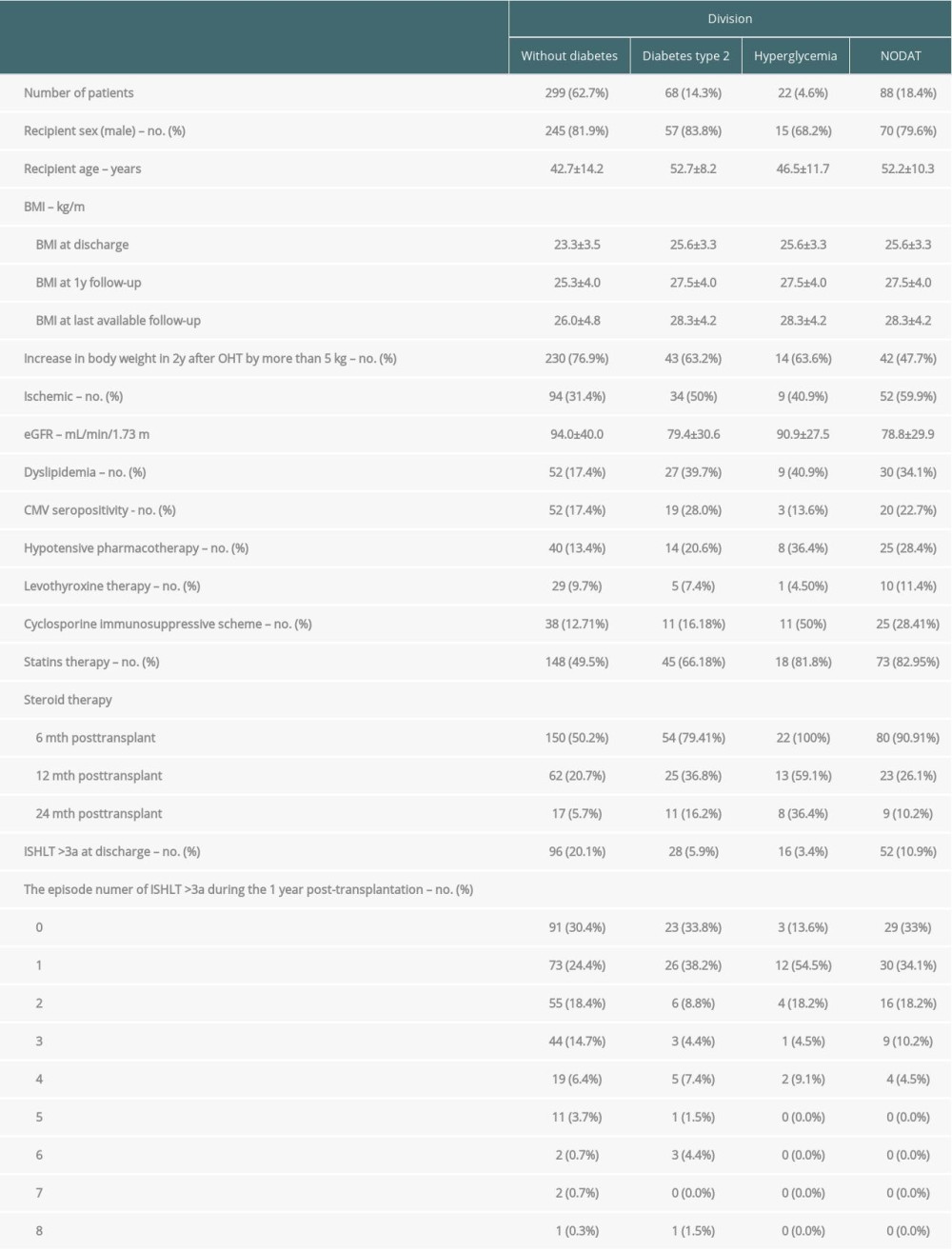

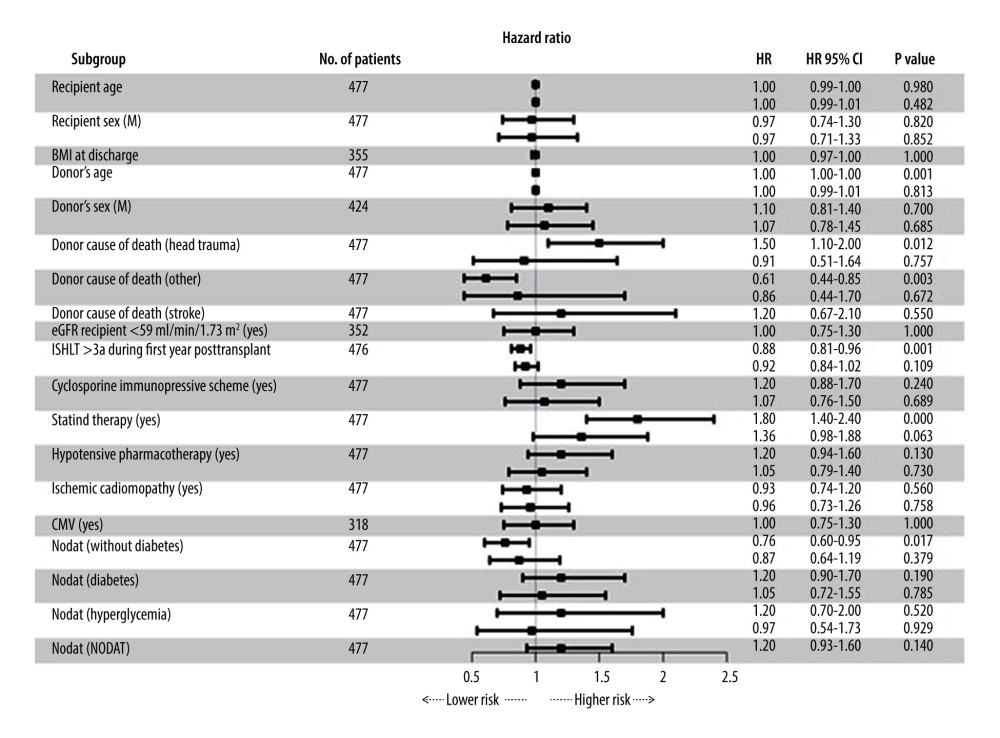

The analyzed data set encompasses 477 heart transplant patients with an average observation time of 13.56±6.92 years. Figure 1 presents the study population and the total number of angiograms taken during the post-transplantation observation. In total, 1442 coronary angiograms were performed in the specified control periods. The clinical characteristics, with a division into 4 sample groups, are presented in Table 1.

A significant majority of patients without diabetes diagnosed during the observation period were male, and they were also younger than the patients with type II diabetes and NODAT. Furthermore, the increase in body mass after 2 years of post-transplantation observation was significantly higher in patients without diagnosed diabetes. Patients with diabetes diagnosed prior to and after transplantation were characterized by decreased renal function, expressed in eGFR. In patients with type II diabetes there was a lower incidence of dyslipidemia and less need for hypotensive pharmacotherapy. On the other hand, patients without diabetes diagnosed during observation were more frequently treated with levothyroxine and statins at the point of discharge from the hospital following HTx. The coronary angiograms performed on patients without diabetes were significantly more likely to exhibit cardiac allograft vasculopathy, expressed in grades >0 per ISHLT.

INCIDENCE OF CAV:

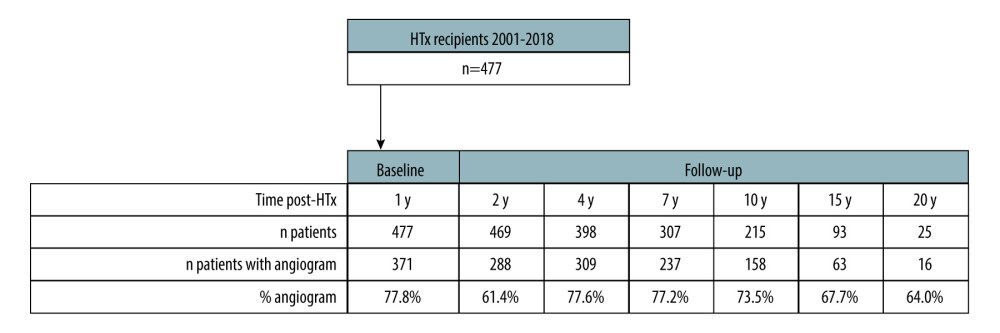

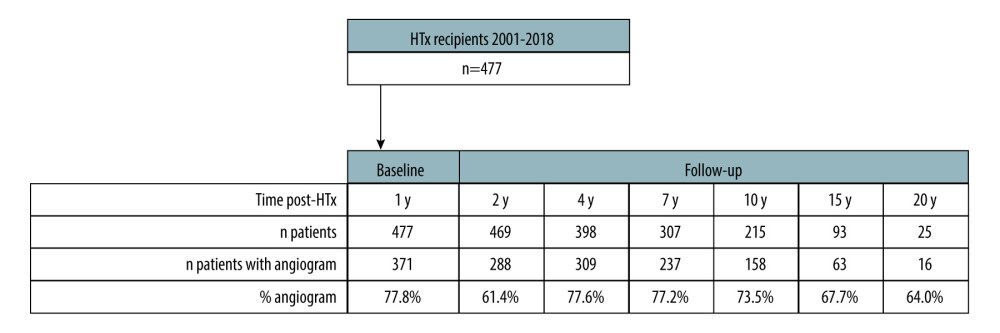

Figure 2 presents the distribution of CAV in heart transplant patients after 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15, and 20 years. The incidence of CAV >0 increased with time after transplantation, reaching 11% after 1 year, 23% after 2 years, 29% after 4 years, 41% after 7 years, 57% after 10 years, 66% after 15 years, and 50% after 20 years following heart transplantation.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SURVIVAL TIME AND THE INCIDENCE OF DIABETES:

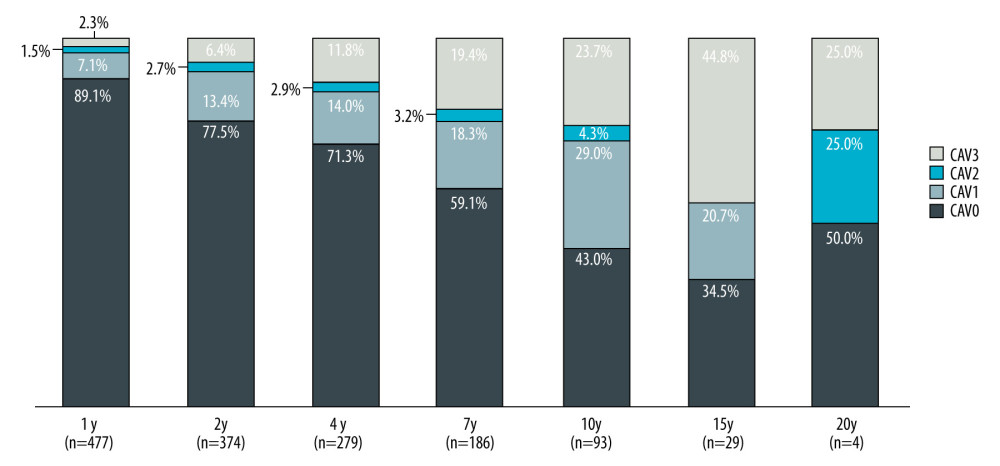

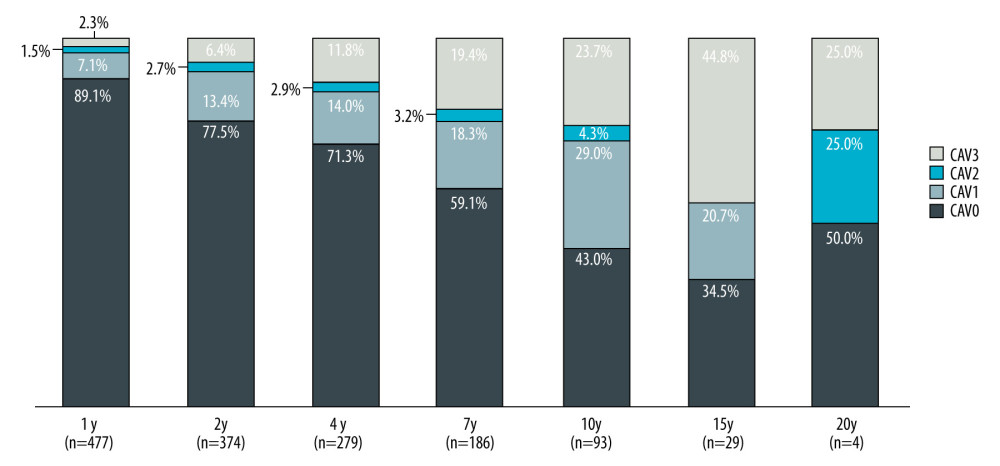

Figure 3 presents survival analysis with a division into 3 groups (patients without diabetes, patients with type II diabetes, and patients with NODAT). The survival of patients with diabetes after transplantation is depicted by the least favorable curve, yet no statistical significance was determined. A deviation of the curve at an extended point in time following transplantation is particularly visible. The longest survival time was observed for patients who had developed type II diabetes prior to heart transplantation.

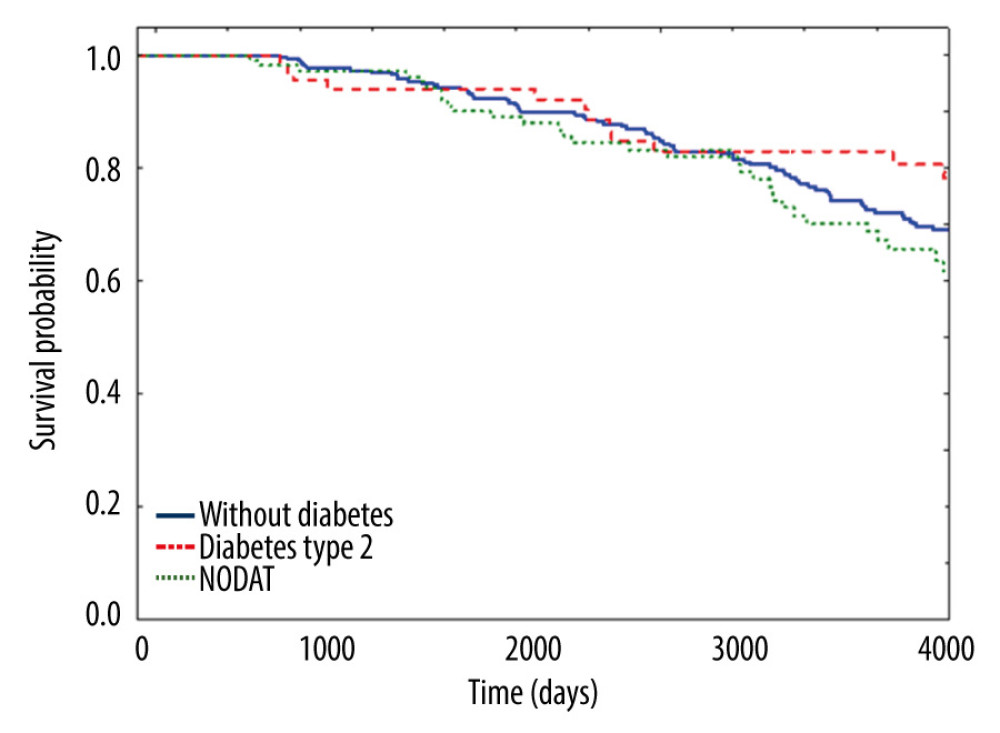

Clinical data were additionally analyzed from the perspective of the risks of developing vasculopathy (Figure 4). In the univariate analysis, significant CAV risk factors included the age of the donor (HR 1.00, P=0.001), head trauma as the donor’s cause of death (HR 1.5, P=0.012), as well as other causes of death, excluding stroke and central nervous system injury (HR 0.61, P=0.003). Additional significant factors included the results of biopsy according to the ISHLT grading scheme signifying cellular rejection (>3a) (HR 1.8, P=0.000) as well as the absence of diabetes over the entire observation period (HR 0.76, P=0.017). The administration of statins during treatment of heart transplant patients exhibited a statistically significant influence in the univariate analysis (HR 1.80, P=0.000). The multivariate analysis failed to identify an independent risk factor for developing cardiac allograft vasculopathy.

Discussion

The source of cardiac allograft vasculopathy may lie in endothelial dysfunctions or atheromatous plaques present in the coronary vessels of both the donor and the recipient. Allograft vasculopathy is a term that describes a process that differs from standard atherosclerosis in a physiological and pathophysiological manner. Some transplanted hearts exhibit classic atheromatous plaques, which were transferred together with the organ, and are referred to as “passenger atherosclerosis.”

There is a clear increase in the incidence of CAV in older men who are transplant recipients [23–25]. CAV develops more often in hearts obtained from older donors, but is less frequent in female donors, but this was not confirmed in our study group.

Currently, the primary risk factor influencing the development of CAV is acute cellular rejection (ACR) during the first year after transplantation, expressed in the present study as ISHLT >3a. Acute cellular rejection occurs most frequently during the first 6 months after heart transplantation, and HTx recipients typically experience an average of 1 ACR episode during the first year [24]. In our study, 69% of follow-up patients had at least 1 ACR during the first year after HTx.

Efforts to standardize the definition of rejection were attempted for a long time, but it was only made possible with the introduction of the biopsy-based grading scheme proposed in 1990 (and modified in 2004) by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Most medical centers do not perform coronary angiography in the first year after transplantation, which is why histopathologic findings are primarily taken into consideration.

The conclusions of research concerning acute rejection from before the biopsy-based ISHLT grading scheme was developed should be approached with caution, as the lack of standardized criteria led to significant discrepancies in the obtained results.

It is reasonable to assume that immunologic activation can result in vasculitis and lead to a heightened risk of CAV. Numerous studies have proven that the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy is dependent on both immunologic and non-immunologic factors (eg, cold ischemia time).

Patel and Kobashigawa demonstrated that performing a cardiac muscle biopsy after the first year following surgery does not have a significant influence on survival time [26]. Up to 20% of the cases exhibit a false-negative rejection result during biopsy. The use of non-invasive monitoring should be considered in the future, including troponin measurements, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and imaging with the use of radiolabeled lymphocytes and anti-myosin antibodies or annexin V [27,28].

The cytomegalovirus (CMV) is one of the most common and clinically significant causes of post-transplant infection, affecting up to 80% of heart and lung transplant recipients. Despite having an available and effective antiviral medication for the prevention and treatment of CMV infections, due to the immunosuppressive burden and the particular characteristics of transplantation, CMV infection remains the primary clinical issue in heart and lung transplant recipients [29,30]. It is suggested that the significant relationship between a CMV infection and early CAV is most likely associated with direct endothelial injury or more frequent rejections. Prophylaxis for reducing asymptomatic CMV infections is additionally associated with lower CAV development [31].

The role of CMV in the development of CAV has been extensively analyzed, but a positive relationship was not confirmed in our study. The discrepancy in the results suggests the need to conduct further research and perform prospective assessment of heart transplant patient therapy.

Tramblay-Gravelet et al, using univariate analysis, indicated that post-transplant diabetes was related to higher mortality among 298 patients who underwent a heart transplantation between 1983 and 2011 at the Montreal Heart Institute. However, this finding has never been confirmed in multivariate analysis, nor has it been proved to be linked with disease progression [32]. Also, among the patients analyzed in our research, the presence of the diabetes did not have any significant impact on developing the allograft vasculopathy and, as a result, on the mortality in this particular patient sample. These conclusions confirm the earlier observations that the risk factors of CAV are slightly different than those related to development and complications of CAD in patients who had never undergone a heart transplant [33].

The present single-center cohort study described in this paper contains a review of the incidence of CAV and the risk factors and survival prognosis depending on the presence of type II diabetes and diabetes after transplantation in the observed patients. The incidence of CAV after 1 year was comparable to the incidence in the ISHLT register and the Leuven single-center study [34], although in subsequent control periods the incidence was slightly higher, but with a stable falling tendency.

Nevertheless, the present study has a number of limitations. First of all, it was a single-center study, whereas the subject of study itself is of an extremely pioneering character in Europe. The issue was approached only by the research center in Leuven [34], but the influence of glucose metabolism disorders was not evaluated. Secondly, given the subclinical coronary incidents, events occurring between the planned angiograms listed in the protocol must not be excluded. Thirdly, the intensification of CAV was assessed only by means of angiography, which is less sensitive to the early stages of CAV than intravascular USG or optical coherence tomography. Due to the observational character of the study, the authors were unable to assess the influence of therapeutic interventions after CAV detection and treatment. The primary advantage of this cohort study is the long observation period (up to 20 years after HTx) and relatively strict follow-up schedule, which enabled a low rate of follow-up loss.

Conclusions

To conclude, the incidence of CAV remains high. Considering the lack of risk factors identified in the multivariate analysis, diagnosing CAV will most likely continue to pose a major challenge in the future. It is therefore necessary to conduct further research to determine other factors that influence the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy during long-term observation.

Figures

Figure 1. Selection of the studied population and the total number of angiograms taken 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15, and 20 years after heart transplantation (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 1. Selection of the studied population and the total number of angiograms taken 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15, and 20 years after heart transplantation (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).  Figure 2. Incidence of CAV over time (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 2. Incidence of CAV over time (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).  Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with division into 3 groups (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with division into 3 groups (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).  Figure 4. Chart presenting the results of the analysis of risk factors for developing CAV, using Cox proportional-hazards models. A univariate analysis was performed for all the risk factors. The multivariate model only contains variables with a sufficient number of observations. For risk factors with both types of regression, univariate and uncorrected HR values are presented above, whereas corrected HR values with multiple variables can be found below (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 4. Chart presenting the results of the analysis of risk factors for developing CAV, using Cox proportional-hazards models. A univariate analysis was performed for all the risk factors. The multivariate model only contains variables with a sufficient number of observations. For risk factors with both types of regression, univariate and uncorrected HR values are presented above, whereas corrected HR values with multiple variables can be found below (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft). References

1. Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, The international thoracic organ transplant registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: Thirty-fifth adult heart transplantation report – 2018; focus theme: Multiorgan transplantation: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2018; 37; 1155-68

2. Milczarek M, Wojciechowska M, Mamcarz A, Cardiac allograft vasculopathy – new trends in diagnostics and treatment: Folia Cardiol, 2017; 12; 50-54

3. Valderhaug TG, Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, The association of early post-transplant glucose levels with long-term mortality: Diabetologia, 2011; 54; 1341

4. Eide IA, Halden TA, Hartmann A, Mortality risk in post- transplantation diabetes mellitus based on glucose and HbA1c diagnostic criteria: Transpl Int, 2016; 29; 568

5. Cosio FG, Kudva Y, van der Velde M, New onset hyperglycemia and diabetes are associated with increased cardiovascular risk after kidney transplantation: Kidney Int, 2005; 67; 2415

6. Wauters RP, Cosio FG, Suarez Fernandez ML, Cardiovascular consequences of new-onset hyperglycemia after kidney transplantation: Transplantation, 2012; 94; 377

7. Yusen RD, Christie JD, Edwards LB, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirtieth Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Report – 2013; Focus theme: Age: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2013; 32(10); 965-78

8. Zimmer RJ, Lee MS, Transplant coronary artery disease: JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2010; 3(4); 367-77

9. Mallah SI, Atallah B, Moustafa F, Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for prevention and management of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: Prog Cardiovasc Dis, 2020; 63(3); 194-209

10. Chih S, Chong AY, Mielniczuk LM, Allograft vasculopathy: The Achilles’ heel of heart transplantation: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016; 68; 80-91

11. Sato T, Seguchi O, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Risk stratification for cardiac allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant recipients – annual intravascular ultrasound evaluation: Circ J, 2016; 80(2); 395-403

12. Chamorro CI, Almenar L, Martínez-Dolz L, Do cardiovascular risk factors influence cardiac allograft vasculopathy?: Transplant Proc, 2006; 38(8); 2572-74

13. Rickenbacher PR, Pinto FJ, Lewis NP, Correlation of donor characteristics with transplant coronary artery disease as assessed by intracoronary ultrasound and coronary angiography: Am J Cardiol, 1995; 76(5); 340-45

14. Spitaleri G, Farrero Torres M, Sabatino M, Potena L, The pharmaceutical management of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation: Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2020; 21(11); 1367-76

15. Das BB, Lacelle C, Zhang S, Gao A, Fixler D, Complement (C1q) binding de novo donor-specific antibodies and cardiac-allograft vasculopathy in pediatric heart transplant recipients: Transplantation, 2018; 102; 502-9

16. Kapadia SR, Nissen SE, Ziada KM, Impact of lipid abnormalities in development and progression of transplant coronary disease: A serial intravascular ultrasound study: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2001; 38; 206-13

17. Stoica SC, Cafferty F, Pauriah M, The cumulative effect of acute rejection on development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2006; 25; 420-25

18. Peled Y, Klempfner R, Kassif Y, Preoperative statin therapy and heart transplantation outcomes: Ann Thorac Surg, 2020; 110; 1280-85

19. Costanzo MR, Dipchand A, Starling RInternational Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines, The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2010; 29(8); 914-56

20. Mehra MR, Crespo-Leiro MG, Dipchand A, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation working formulation of a standardized nomenclature for cardiac allograft vasculopathy – 2010: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2010; 29; 717-27

21. Bergrem HA, Valderhaug TG, Hartmann A, Undiagnosed diabetes in kidney transplant candidates: A case-finding strategy, Clin J Am So: Nephrol, 2010; 5; 616-22

22. Sharif A, Hecking M, De Vries APJ, Proceedings from an international consensus meeting on posttransplantation diabetes mellitus: Recommendations and future directions: Am J Transplant, 2014; 14; 1992-2000

23. Prieto D, Correia P, Baptista M, Antunes MJ, Outcome after heart transplantation from older donor age: Expanding the donor pool: Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2015; 47; 672-78

24. Kransdorf EP, Loghmanpour NA, Kanwar MK, Prediction model for cardiac allograft vasculopathy: comparison of three multivariable methods: Clin Transpl, 2017; 31; ctr12925

25. Galli G, Caliskan K, Balk AH, Cardiac allograft vasculopathy in Dutch heart transplant recipients: Neth Heart J, 2016; 24; 748-57

26. Patel JK, Kobashigawa JA, Should we be doing routine biopsy after heart transplantation in a new era of antirejection?: Curr Opin Cardiol, 2006; 21(2); 127-31

27. Hesse B, Mortensen SA, Folke M, Brodersen AK, Ability of antimyosin scintigraphy monitoring to exclude acute rejection during the first year after heart transplantation: J Heart Lung Transplant, 1995; 14(1 Pt 1); 23-31

28. Narula J, Acio ER, Narula N, Annexin-V imaging for noninvasive detection of cardiac allograft rejection: Nat Med, 2001; 7(12); 1347-52

29. Potena L, Solidoro P, Patrucco F, Treatment and prevention of cytomegalovirus infection in heart and lung transplantation: An update: Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2016; 17(12); 1611-22

30. Potena L, Grigioni F, Magnani G, Prophylaxis versus preemptive anti-cytomegalovirus approach for prevention of allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant recipients: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2009; 28(5); 461-67

31. Valantine H, Gao S, Menon S, Impact of prophylactic immediate posttransplant ganciclovir on development of transplant atherosclerosis. A post hoc analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled study: Circulation, 1999; 100(1); 61-66

32. Tremblay-Gravel M, Racine N, de Denus S, Changes in outcomes of cardiac allograft vasculopathy over 30 years following heart transplantation: JACC Heart Fail, 2017; 5(12); 891-901

33. Schmauss D, Weis M, Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: Recent developments: Circulation, 2008; 117; 2131-41

34. Van Keer JM, Van Aelst LNL, Rega F, Long-term outcome of cardiac allograft vasculopathy: Importance of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation angiographic grading scale: J Heart Lung Transplant, 2019; 38(11); 1189-96

Figures

Figure 1. Selection of the studied population and the total number of angiograms taken 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15, and 20 years after heart transplantation (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 1. Selection of the studied population and the total number of angiograms taken 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 15, and 20 years after heart transplantation (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft). Figure 2. Incidence of CAV over time (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 2. Incidence of CAV over time (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft). Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with division into 3 groups (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with division into 3 groups (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft). Figure 4. Chart presenting the results of the analysis of risk factors for developing CAV, using Cox proportional-hazards models. A univariate analysis was performed for all the risk factors. The multivariate model only contains variables with a sufficient number of observations. For risk factors with both types of regression, univariate and uncorrected HR values are presented above, whereas corrected HR values with multiple variables can be found below (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft).

Figure 4. Chart presenting the results of the analysis of risk factors for developing CAV, using Cox proportional-hazards models. A univariate analysis was performed for all the risk factors. The multivariate model only contains variables with a sufficient number of observations. For risk factors with both types of regression, univariate and uncorrected HR values are presented above, whereas corrected HR values with multiple variables can be found below (STATISTICA 13.3 by StatSoft). In Press

18 Mar 2024 : Original article

Does Antibiotic Use Increase the Risk of Post-Transplantation Diabetes Mellitus? A Retrospective Study of R...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943282

20 Mar 2024 : Original article

Transplant Nephrectomy: A Comparative Study of Timing and Techniques in a Single InstitutionAnn Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942252

28 Mar 2024 : Original article

Association Between FEV₁ Decline Rate and Mortality in Long-Term Follow-Up of a 21-Patient Pilot Clinical T...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942823

02 Apr 2024 : Original article

Liver Transplantation from Brain-Dead Donors with Hepatitis B or C in South Korea: A 2014-2020 Korean Organ...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943588

Most Viewed Current Articles

05 Apr 2022 : Original article

Impact of Statins on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Living-Donor Liver TransplantationDOI :10.12659/AOT.935604

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935604

12 Jan 2022 : Original article

Risk Factors for Developing BK Virus-Associated Nephropathy: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study of ...DOI :10.12659/AOT.934738

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e934738

22 Nov 2022 : Original article

Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipient...DOI :10.12659/AOT.937988

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e937988

15 Mar 2022 : Case report

Combined Liver, Pancreas-Duodenum, and Kidney Transplantation for Patients with Hepatitis B Cirrhosis, Urem...DOI :10.12659/AOT.935860

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935860