02 March 2021: Original Paper

Kidney Transplant Evaluation and Listing: Development and Preliminary Evaluation of Multimedia Education for Patients

Liise K. Kayler12ABCDE*, Beth Dolph1E, Molly Ranahan2CE, Maria Keller3CE, Renee Cadzow4E, Thomas H. Feeley5CEDOI: 10.12659/AOT.929839

Ann Transplant 2021; 26:e929839

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Patient knowledge gaps about the evaluation and waitlisting process for kidney transplantation lead to delayed and incomplete testing, which compromise transplant access. We aimed to develop and evaluate a novel video education approach to empower patients to proceed with the transplant evaluation and listing process and to increase their knowledge and motivation.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: We developed 2 theory-informed educational animations about the kidney transplantation evaluation and listing process with input from experts in transplantation and communication, 20 candidates/recipients, 5 caregivers, 1 anthropologist, 3 community advocates, and 36 dialysis or transplant providers. We then conducted an online pre-post study with 28 kidney transplantation candidates to measure the acceptability and feasibility of the 2 videos to improve patients’ evaluation and listing knowledge, understanding, and concerns.

RESULTS: Compared with before intervention, the mean knowledge score increased after intervention by 38% (5.7 to 7.9; P<0.001). Increases in knowledge effect size were large across age group, health literacy, education, technology access, and duration of pretransplant dialysis. The proportion of positive responses increased from before to after animation viewing for understanding the evaluation process (25% to 61%; P=0.002) and waitlist placement (32% to 86%; P<0.001). Concerns about list placement decreased (32% to 7%; P=0.039). After viewing the animations, >90% of responses indicated positive ratings on trusting the information, comfort level with learning, and engagement.

CONCLUSIONS: In partnership with stakeholders, we developed 2 educational animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing that were positively received by patients and have the potential to improve patient knowledge and understanding and reduce patient concerns.

Keywords: Kidney Transplantation, Patient Education as Topic, waiting list, Motivation, Multimedia, Renal Dialysis, Waiting Lists

Background

Kidney transplantation improves patient quality and length of life better than does dialysis treatment [1]. Yet, less than 20% of the 501 466 patients in the United States receiving long-term dialysis [2] are on the waiting list for a kidney transplant, and, of those on the list, 40% are ineligible to receive kidney offers owing to an inactive waitlisting status [3]. The low rates of progression to listing placement and maintenance of eligibility while waiting are due, in large part, to patient attrition caused by testing delays and the failure to complete testing. Potential recipients may take as long as a year to complete the transplant evaluation [4], and 50% fail to complete the evaluation stage, despite not having clear contraindications [5,6].

Many research studies have shown that patients are confused about the transplant evaluation and listing process and that these knowledge deficits contribute to testing delays and aborted medical evaluations [7–10]. Knowledge gaps reported by patients include a lack of clarity about where they are in the listing process [9], belief they are already on the list [11,12], lack of awareness that tests need to be repeated [13], and misunderstanding of an inactive status on the list [14]. In addition to difficulties navigating the healthcare system, knowledge gaps may lead to negative perceptions of the transplant process and reduce patient motivation to complete testing [14,15].

Patient education about the kidney transplantation evaluation and listing process typically occurs at transplant centers through educational classes, followed by consultations with multidisciplinary providers, which give patients the opportunity to ask questions. In-person education is supplemented with take-home materials and telephone conversations with transplant coordinators [16]. Patients characterize routine transplant education classes as being lengthy and presenting too much information at once [14,17]. Also, they forget to ask questions while meeting with providers [14], find the take-home print materials overwhelming [14], and do not recognize telephone conversations with coordinators as opportunities for education [14]. Some patients turn to websites to learn about kidney transplantation; however, patients have described publicly available websites as being confusing [18].

To impact the evaluation and listing process through patient education, interventions over the past decade have employed various combinations of trained educators, navigators, videos, and pamphlets [6, 19–23], with some interventions demonstrating effectiveness at increasing transplant evaluations or listings over those that are attained with standard care [6,19–21]. However, the adoption of interventions that require human educators is limited by health system resources and already burdened healthcare staff. One of these interventions resulted in a higher rate of evaluation completion with the use of a video DVD and pamphlet alone than with the use of a video and pamphlet plus an educator [19], highlighting the potential value of stand-alone educational materials. However, the video and pamphlet education had been originally designed to encourage living-donor kidney transplantation and may lack meaningful content about the evaluation and listing process.

There remains a need for effective educational tools that can be efficiently used by healthcare providers to present information to patients or that patients can access independently to learn about the evaluation and listing process. To address this need, we developed 2 animated videos about the kidney transplant evaluation and waiting list process, which were targeted to kidney transplant candidates and their caregivers. The animation format offers efficient learning owing to the enhanced cognitive processing of the medium [24], and it has been found to be accessible across age, culture, and literacy level [25,26].

In this study, we (1) cover the development process of the 2 educational animations about evaluation and listing for kidney transplantation and (2) report preliminary acceptability and feasibility evidence from a pilot test of the animations in an online study that was conducted with potential kidney recipients. The results of the report will contribute to a comprehensive animation-based educational intervention to enhance access to kidney transplantation. This educational intervention will undergo formal program evaluation in the future.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN:

Qualitative methods were employed to develop 2 animations about the process of (1) evaluation and (2) listing for kidney transplantation. These methods were informed by health communication best practices and behavior theories [24,27,28]. We also developed surveys aligned with the animations to test patients’ evaluation and listing knowledge, understanding, and concerns. Next, we performed a preliminary evaluation of both animations with an uncontrolled, single-group, quasi-experimental, pre-post study conducted online. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University at Buffalo, and the protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANIMATIONS:

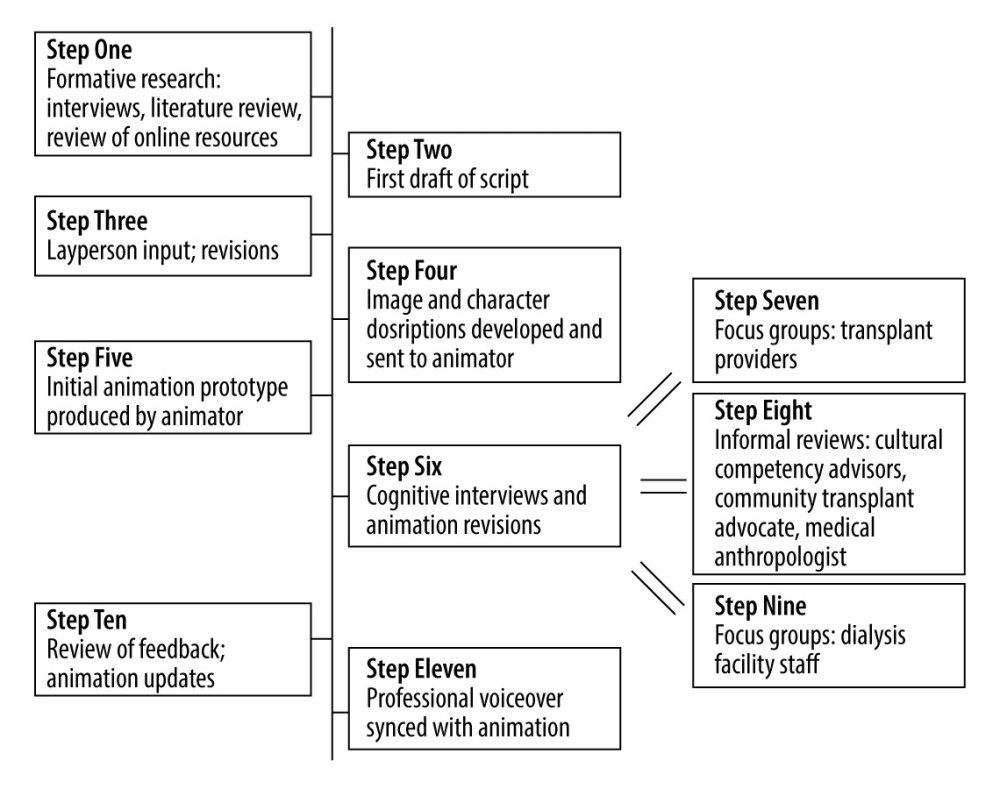

The animations were developed between October 2018 and August 2019 through an 11-step process to gather input to iteratively develop the videos (Figure 1).

In Step 1, we conducted formative research through interviews [14,29] and a review of the published literature [8,11–13,30] and existing online resources to inform our outline for animation content. Key content (Table 1) was considered to be practical (applicable to real-life situations), facilitative (examples of behaviors and solutions), and inclusive of support network roles (friends, family members, and healthcare providers).

In Step 2, a first draft script was created using plain language, conversational style, and active voice. Information was organized following the elaboration theory [27]. Messages were also gain-framed and guided by the self-efficacy theory [28] to incorporate cognitive and emotional processing of health-relevant information [31].

In Step 3, a layperson gave input, and subsequent script revisions were made by the researchers. In Step 4, the researchers developed descriptions for images and characters for each scene or main point. Characters, which were chosen from those produced for videos on different transplant topics [32], were diverse in age, race, and ethnicity. During Step 5, an initial prototype of the animation was produced using line drawings, which were synchronized to a temporary voice over.

Step 6 consisted of cognitive interviews [33] and animation revisions done iteratively following feedback [34], with specific emphasis on providing the information in an emotionally reassuring way. Through convenience sampling, 10 potential kidney transplant recipients, 10 recipients of deceased donor kidneys, and 5 caregivers were approached in the Erie County Medical Center transplant clinic and outpatient dialysis facility to participate in the cognitive interviews, resulting in 7 focus groups and 14 individual interviews. Feedback was solicited immediately after watching the animations (Table 2). We obtained information about the animations’ suitability, acceptability, and anticipated usability and feasibility using an interview guide. Black patients (purposively approached to achieve a minimum of 40% of the sample) were interviewed separately from non-Black patients to promote a range in perspective. These sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Steps 7, 8, and 9 occurred in parallel with Step 6 and consisted of focus groups (Steps 7 and 9) and informal reviews with stakeholders and experts (Step 8, email or in-person reviews). The participants included 12 transplant practitioners, 2 focus groups, 2 hospital-based experts on cultural competency, a local kidney advocate from the Kidney Foundation of Western New York, a medical anthropologist, and 24 dialysis unit staff. The informal reviews were documented with field notes. The focus groups were audio recorded.

In Step 10, two researchers listened to and read the transcripts for each audio recording, consulted researcher notes, and selected messages reflective of each interview’s context to capture meaningful feedback. Findings were promptly reported to the research team for consideration in the refinement of the animations. Updates to the narration, scripts, graphics, pacing, and animation were made based on ongoing feedback until the animations were finalized. Animation design was based on animation multimedia learning theory [24], which describes the method of synchronizing audio and visual information to enhance message comprehension. In Step 11, a professional voice over was set to the animations.

DEVELOPMENT OF SURVEYS:

An interdisciplinary team of transplant practitioners and researchers designed questions that were aligned with animation content and written using simple language to measure kidney evaluation and listing knowledge, understanding, and concerns. Research staff conducted cognitive interviews with 7 deceased donor kidney transplantation (DDKT) recipients regarding question clarity. Participants identified questions that were confusing and words that needed clarification.

FINAL ANIMATION TESTING FOR FEASIBILITY AND ACCEPTABILITY:

The animations were evaluated with patients who were referred for kidney transplantation to Erie County Medical Center in New York between May 2020 and July 2020. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, English-speaking, non-incarcerated, email available in the administrative record, and no previous attendance at a kidney transplant evaluation at the medical center. Some patients had already attended standard transplant education consisting of a 2-h oral and PowerPoint lecture presented in a group setting by a transplant nurse, which covered the kidney transplantation process, benefits, and risks. Others had not attended because the group education session had been replaced by one-on-one education administered on the same day as the transplant evaluation because of the cessation of group-based activities in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

To recruit participants, consecutive kidney transplant candidates that had been referred to the transplant center and completed the clinical intake telephone call were emailed letters of invitation to the study. Those that did not opt out received a maximum of 2 telephone calls (and additional concurrent text and email invitations if nonresponsive to calls) 1 week apart. After patients gave their consent verbally or by email or text, the patient received an email containing a link to the study. The study link was valid until their transplant medical evaluation visit at the hospital or until the end of the study, whichever came first. The link opened to the study and included an electronic consent, all survey instruments, and both videos back-to-back on a SurveyGizmo platform (Boulder, CO, USA). We developed the features of the study platform based on usability feedback that we received from transplant candidates at our center, which had led to a simple context-sensitive interface [35].

Participants opened the study link on the device of their choice and completed the following: electronic consent, 31 questions including sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race, education, employment, total annual household income, and marital status), pretransplant dialysis duration, health literacy [36], technology access [37], and measures of evaluation and listing knowledge (9 items, true/false/I don’t know), understanding (3 items, 5-point Likert scale), and concerns (2 items, 5-point Likert scale). After survey completion, the participants were routed to a page with the first animation (about evaluation), which started automatically after a 3 s lag. After the video reached the end, a “next” button would appear. When the “next” button was pushed, a page with the second animation (about listing) would appear and play automatically. Both videos could be paused and replayed an unlimited number of times. After video viewing was complete, participants answered 1 question about whether they watched the videos and the device used, followed by survey questions identical to the pre-tests, with the sociodemographic questions replaced by animation acceptability questions (11 items, 5-point Likert scale), which was developed by the researchers (α=0.92) [38]. All survey questions were required and posed sequentially without the option of going backward. Participants were compensated with a $25.00 check.

SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION:

We determined that patient-level changes in evaluation and listing knowledge, understanding, and concerns before and after study with 24 participants would provide 80% power to detect at least a 0.60 standardized effect size using a 1-group

DATA ANALYSIS:

Parallel to the collection of the qualitative data, the data were analyzed. Transcripts were reviewed and manually coded by a single investigator. All utterances were assigned to as many different concepts as they fit and then were grouped into similar themes related to the study aims. The findings were discussed with a second investigator with expertise in qualitative analyses.

SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform quantitative statistical analyses. Frequencies were computed for all categorical variables and compared using the McNemar’s test. As a measure of effect sizes, point biserial correlation [39] was calculated with 0.1, 0.2, and 0.32 representing small, medium, and large effects, respectively. Knowledge scores (with unsure and unanswered questions considered as false) were calculated by adding the number of correct answers. All Likert scales, which were previously bounded by strongly agree and strongly disagree, were dichotomized for ease of interpretation. Higher scores reflected greater understanding and concerns. Animation acceptability data were categorized and presented in a histogram. A 2-tailed alpha of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

VIDEO DEVELOPMENT:

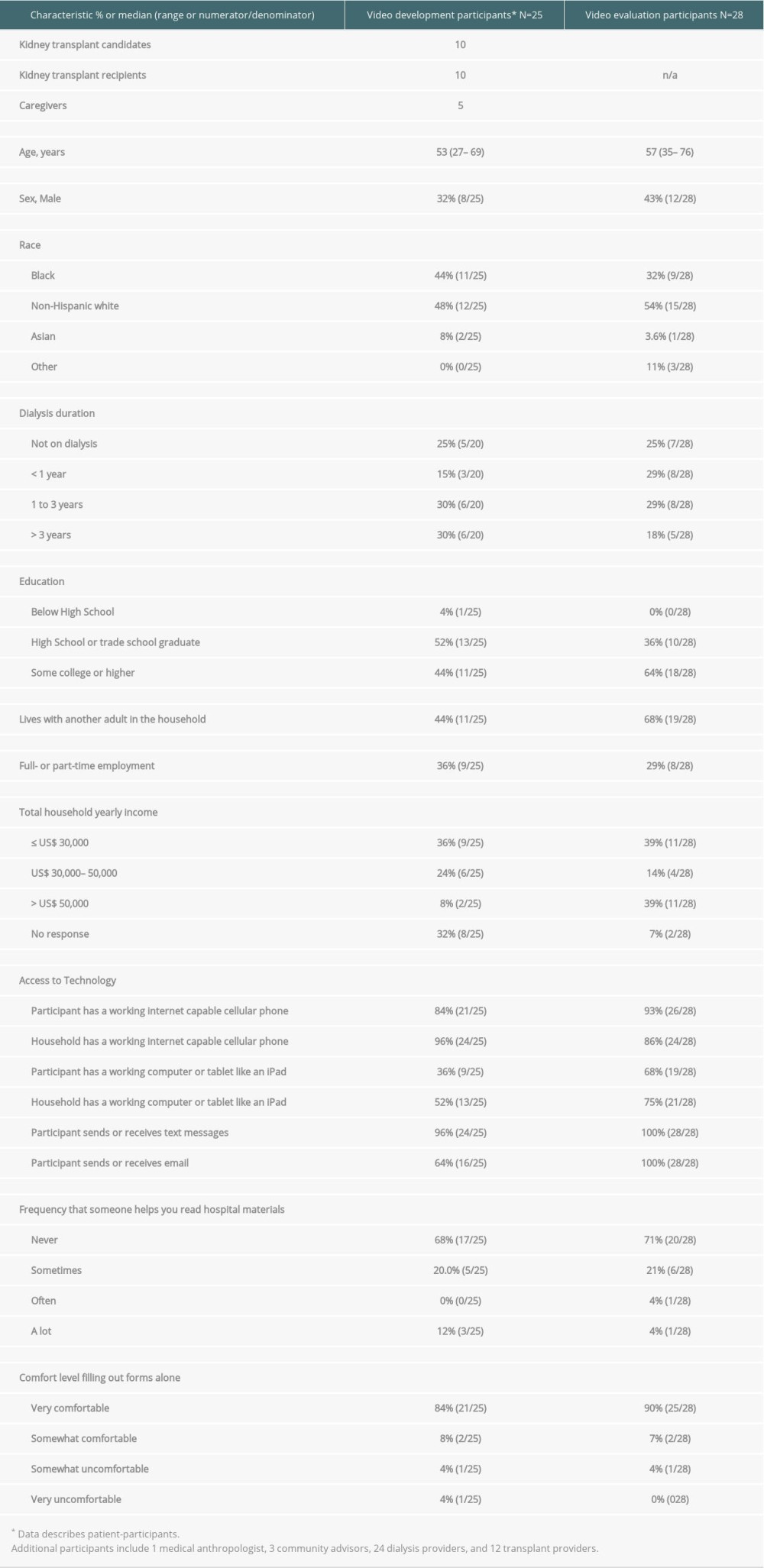

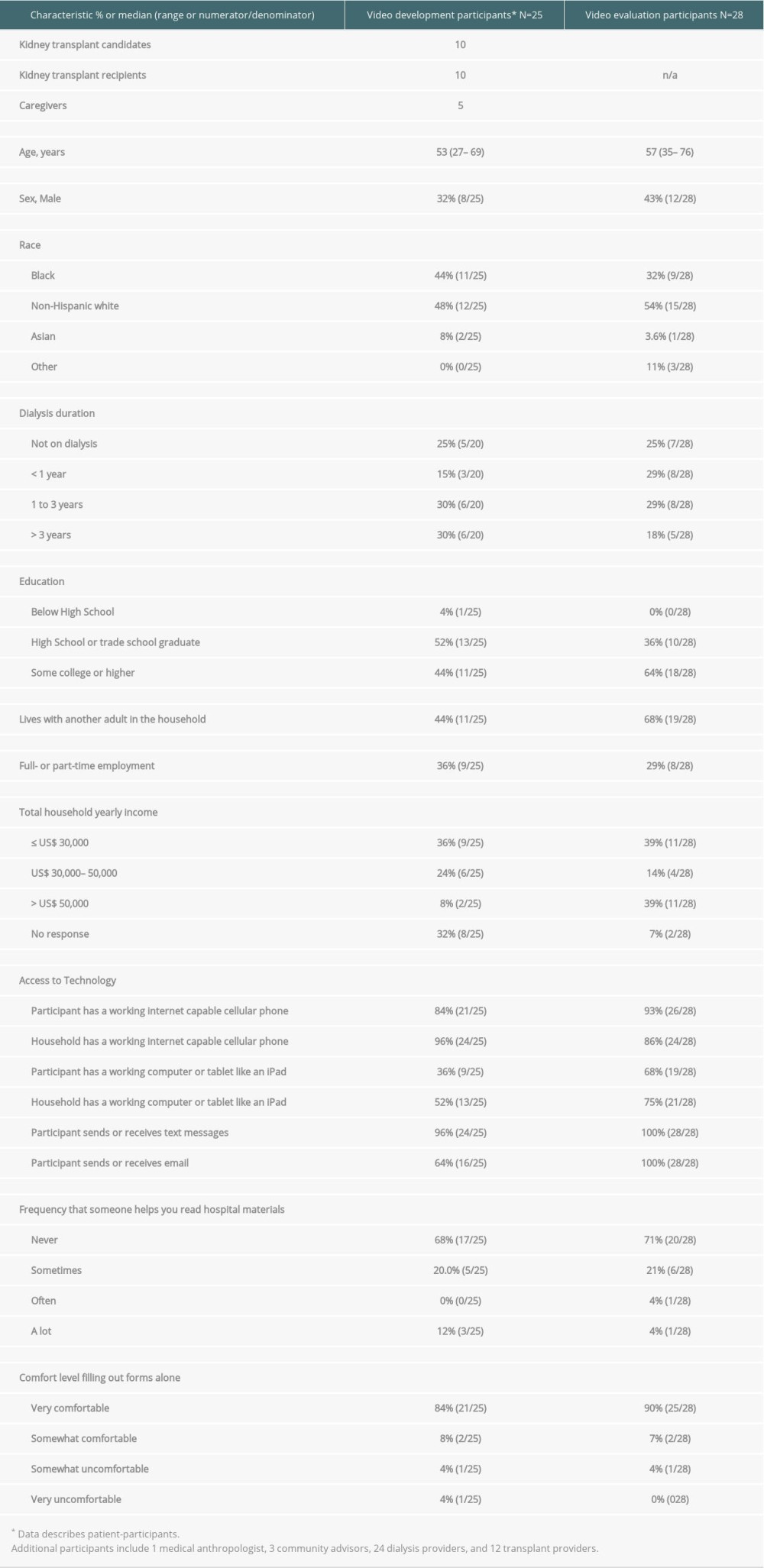

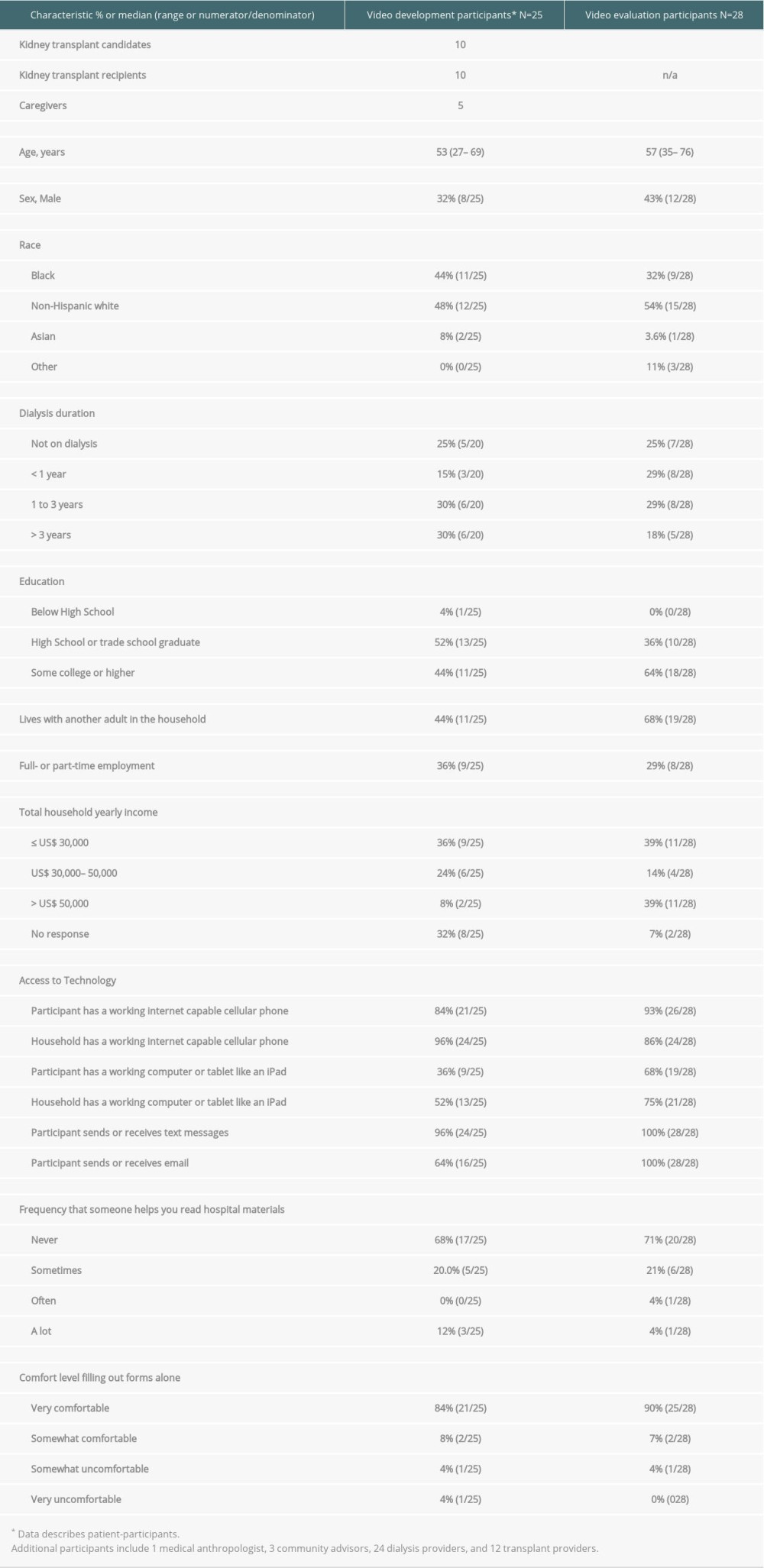

A total of 25 participants completed the cognitive interviews to help direct the development of the videos. Their ages ranged between 27 to 69 years; 8 were men; 11 were Black, 12 White, and 2 Asian; 11 had completed some college; most had annual household incomes between $30 000 and $50 000 or less; 10 were potential kidney transplant recipients, 5 were caregivers; and 10 had received DDKTs (Table 3). The roles of the experts and stakeholders, who also provided input, are shown in Table 3.

The process of video development (Table 2) began with an early prototype of a single video that covered topics about both the medical evaluation and kidney transplant waiting list. Some participants were confused by the extensive content and stated the video was too long and had too much information. Therefore, the video was split into 2 separate videos. Subsequent interviews included viewing of both animations.

Feedback regarding the evaluation animation noted the following: the video did not show the specific tests that needed to be obtained; the person who schedules the appointments was not shown; the procedure when there are “problematic” test results was not addressed; and how the committee decision is conveyed to the patient was not addressed. Patients also recommended that the candidate should be told to bring a snack to the evaluation and that the video should describe the medical background of the transplant coordinator. The dialysis staff members said there should be an explanation that some test results lead to the requirement of other tests. These aspects were added.

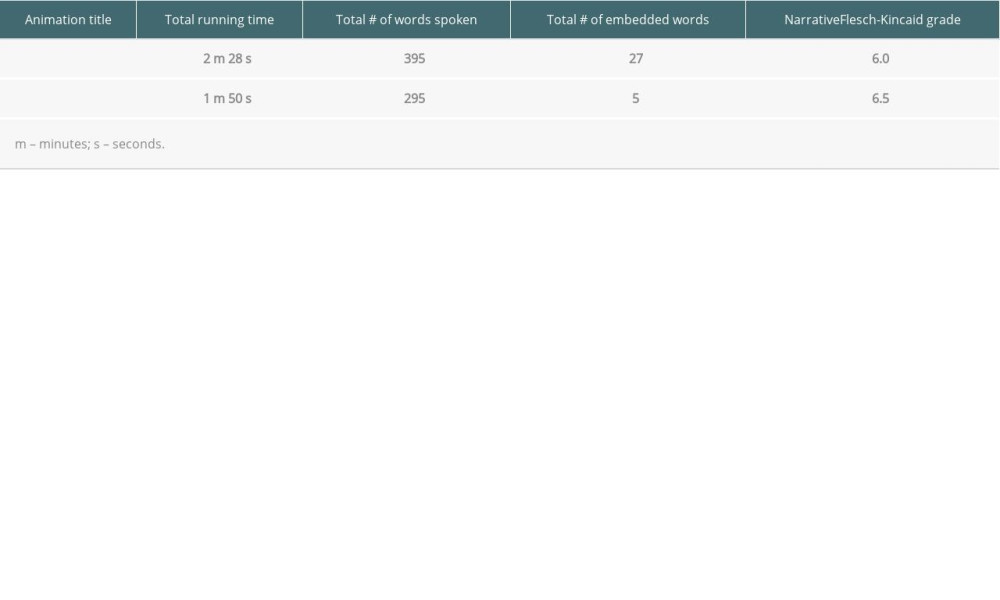

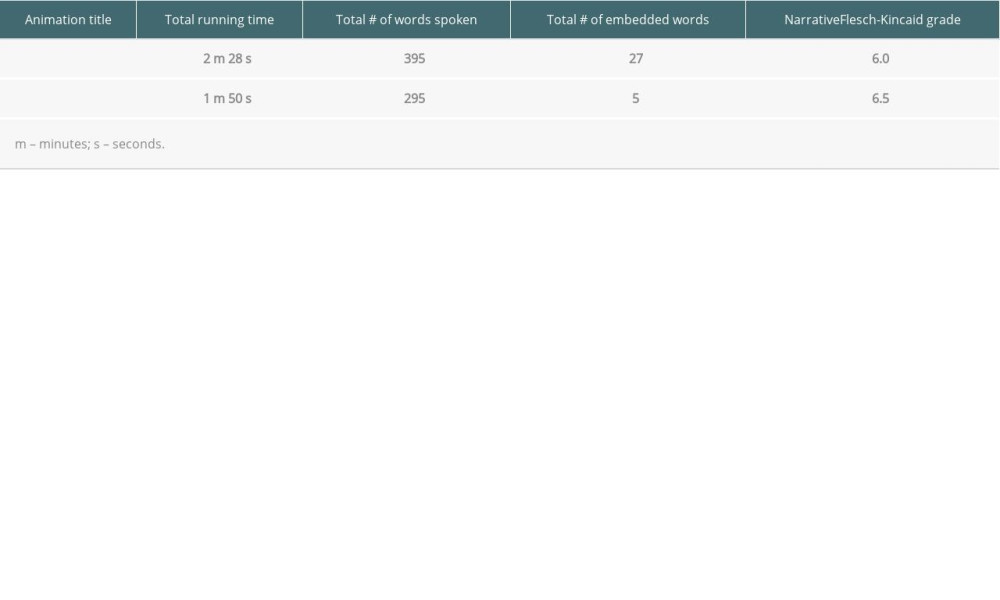

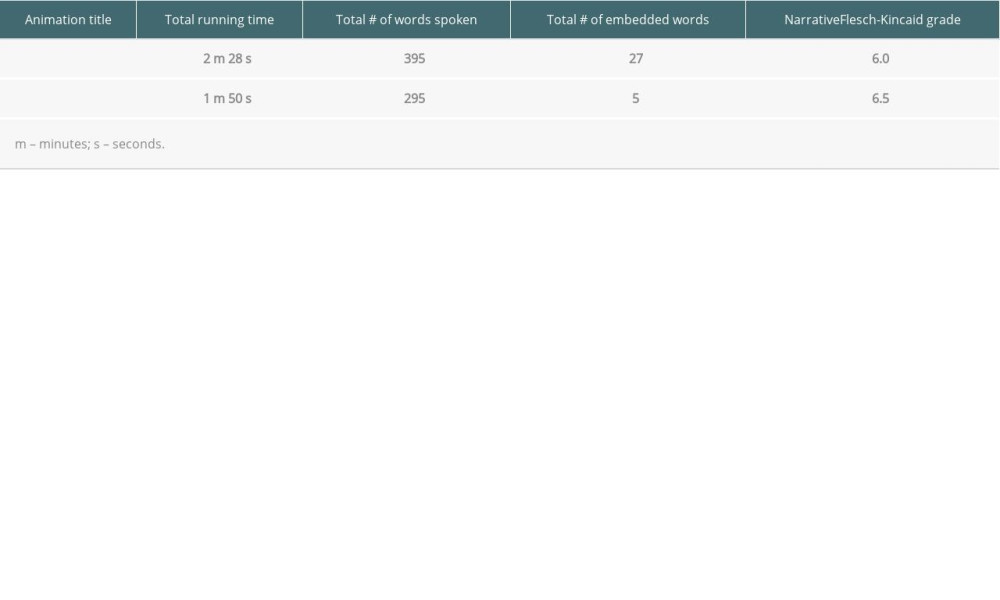

Feedback from the dialysis staff members and patients regarding the video about the waiting list included that the explanations of active and inactive status were confusing. Extensive revisions were made in response to their comments until the content was understood as intended. We also received feedback suggesting the inclusion of a summary statement. An epilogue of the major educational topics in each video was created and retained for the waitlisting video, but was not retained in the evaluation video because it caused confusion. Two animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing were produced, each approximately 2 min in duration. The content of the videos is described in Table 1, and their titles and data are depicted in Table 4.

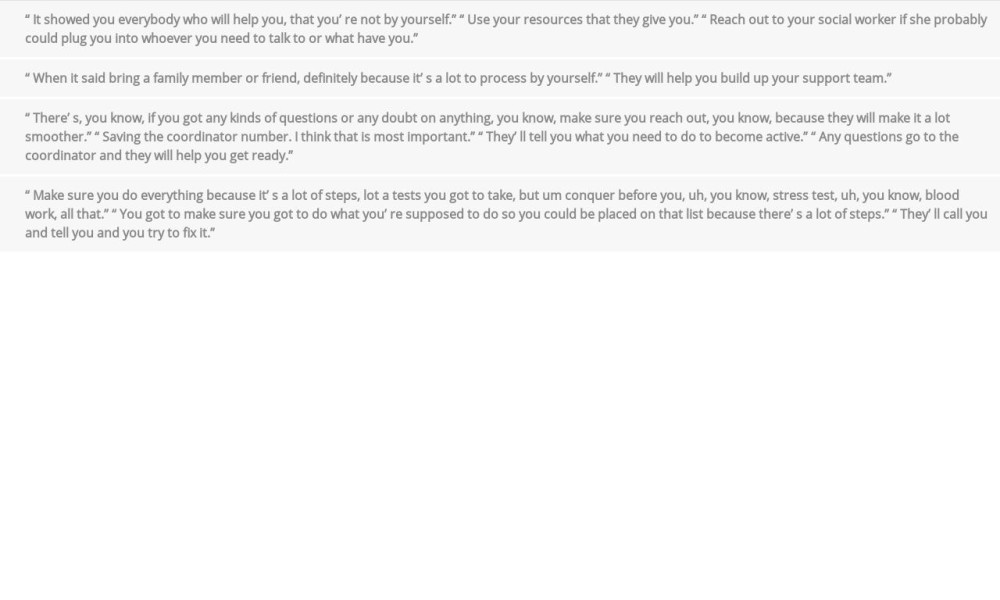

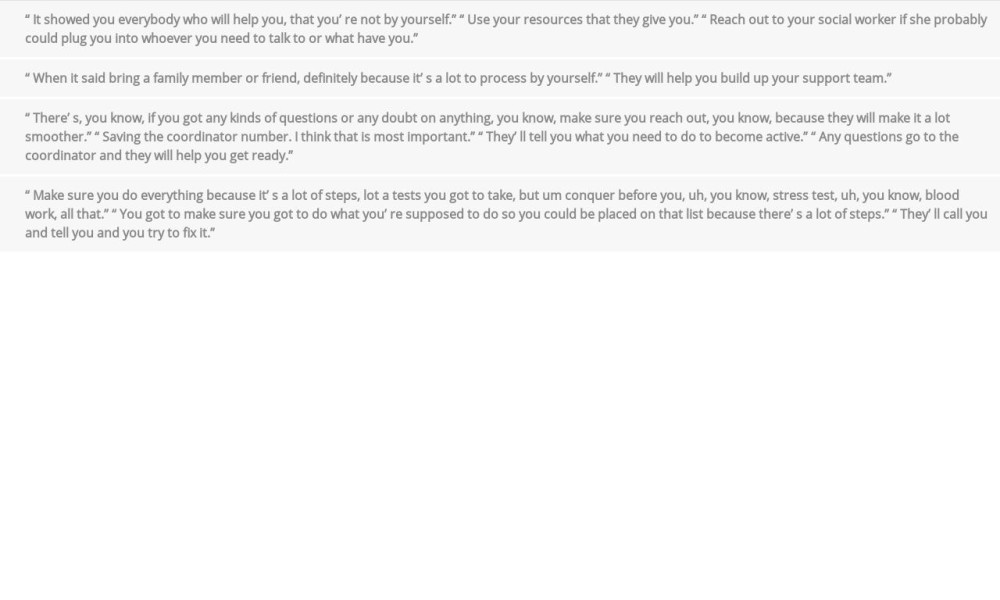

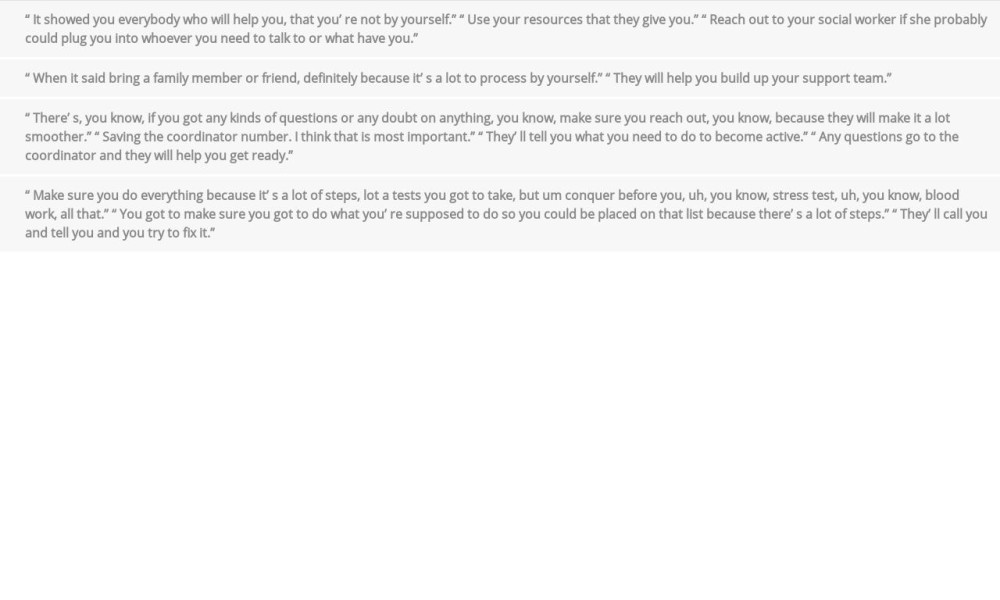

The following 4 themes were identified from patient feedback about the videos: resources and support, caregiving, communication, and follow-through (Table 5). (1) Patients identified messages about the availability of resources and providers being there “to help you”. (2) Caregivers were described as helping patients remember information and provide support. (3) Feedback within the communication theme included knowing the coordinator’s contact information, reaching out, asking questions, and learning what to do. (4) Follow-through was described as “conquering” test completion and addressing results that required further testing to “get on the list”.

VIDEO EVALUATION PILOT STUDY:

Of the 164 patients referred to the transplant center during the study time period, email addresses were available for 107 patients, who were invited to participate, and 32 patients provided consent (30% recruitment). Reasons given for nonparticipation were lack of availability, feeling sick, visual or motor impairment, poor Internet, and reason not given. Of the 32 consenting participants, 28 completed the study. Table 3 depicts the demographic data of the 28 participants included in the final analytic sample. The patients’ median age was 57 years; 43% were men; 32% were Black, 54% White, and 11% Asian; 36% completed secondary education or less. The total household income was <$30 000 annually among 39%, and the proportion that was unemployed was 29%. The majority (93%) owned a cell phone with Internet capability, and 100% used text messages. The device used to complete the study was computer/tablet for 25%, cell phone for 71%, and unknown for 4%.

KNOWLEDGE:

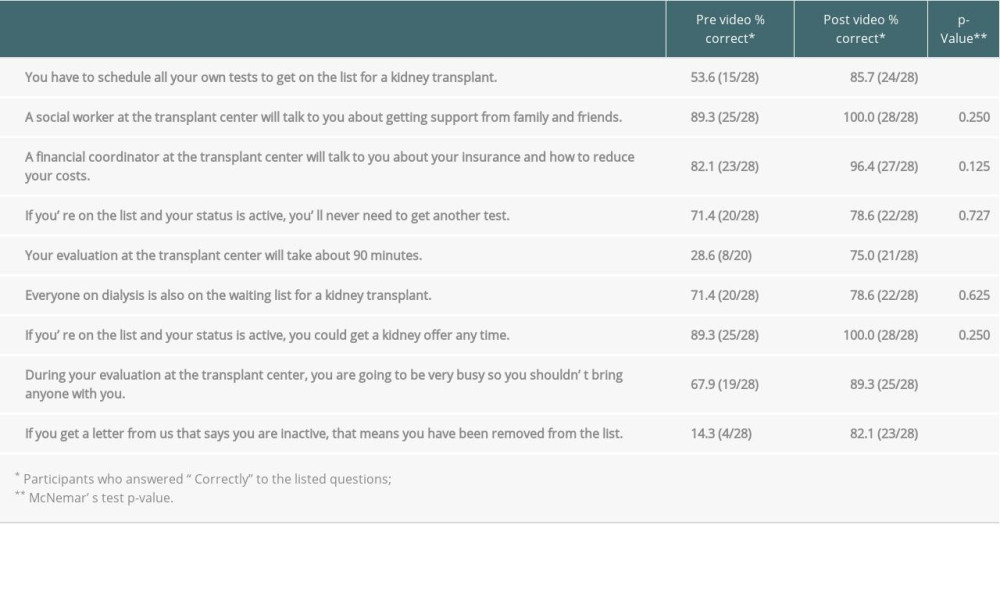

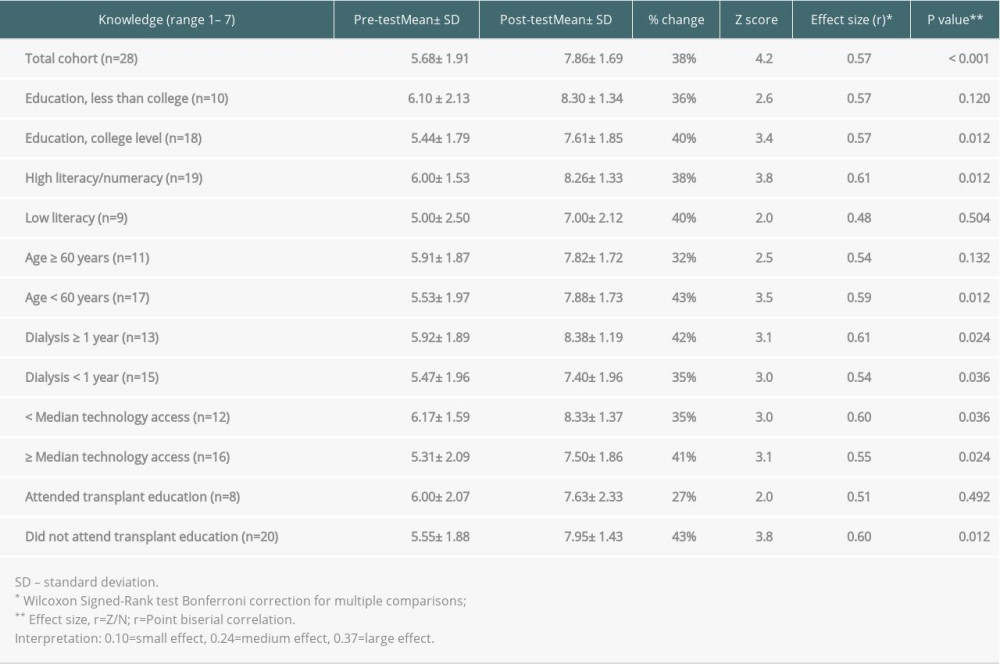

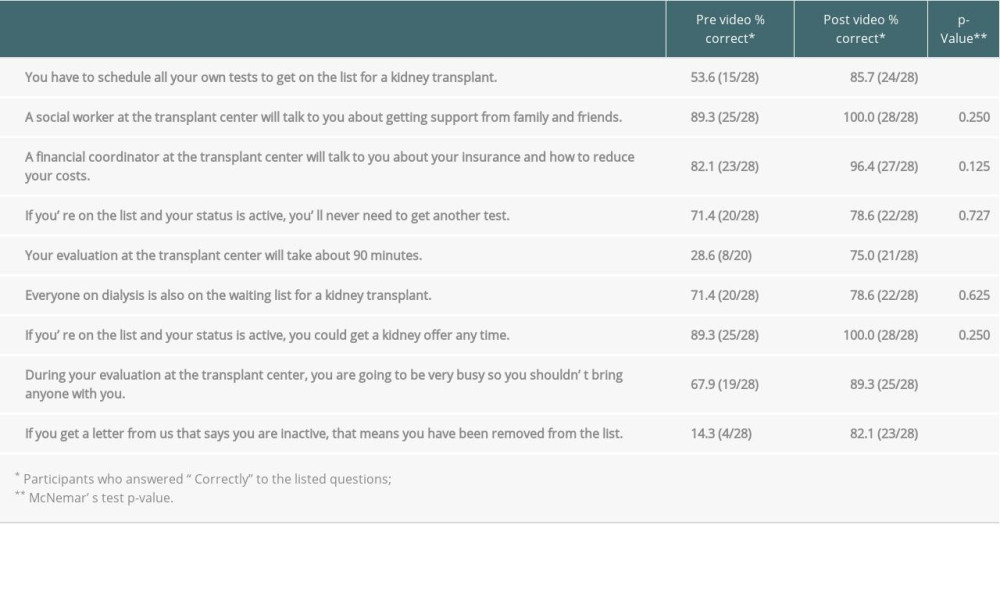

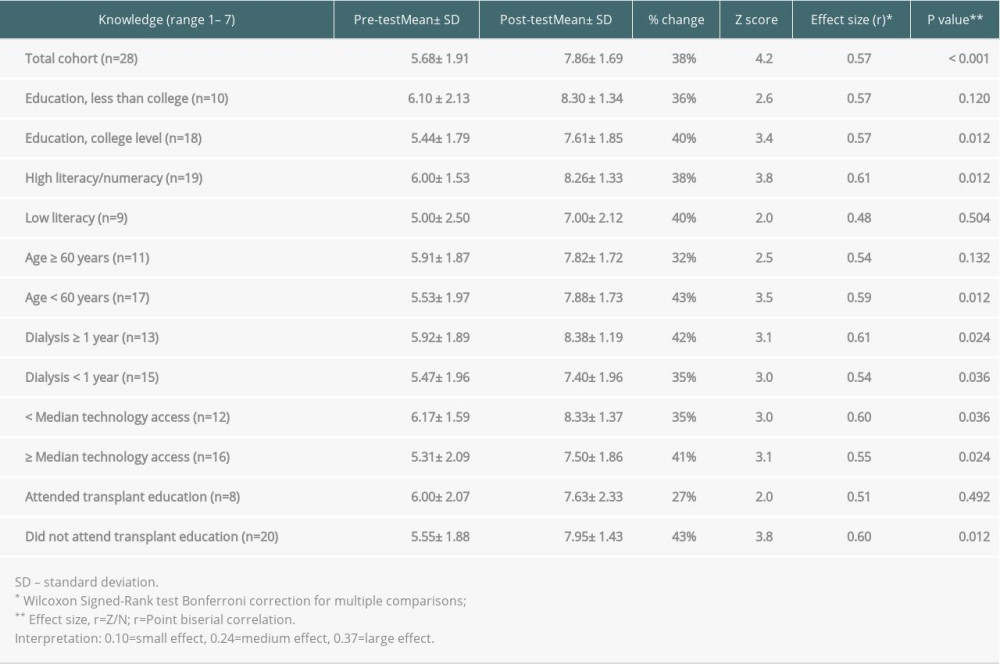

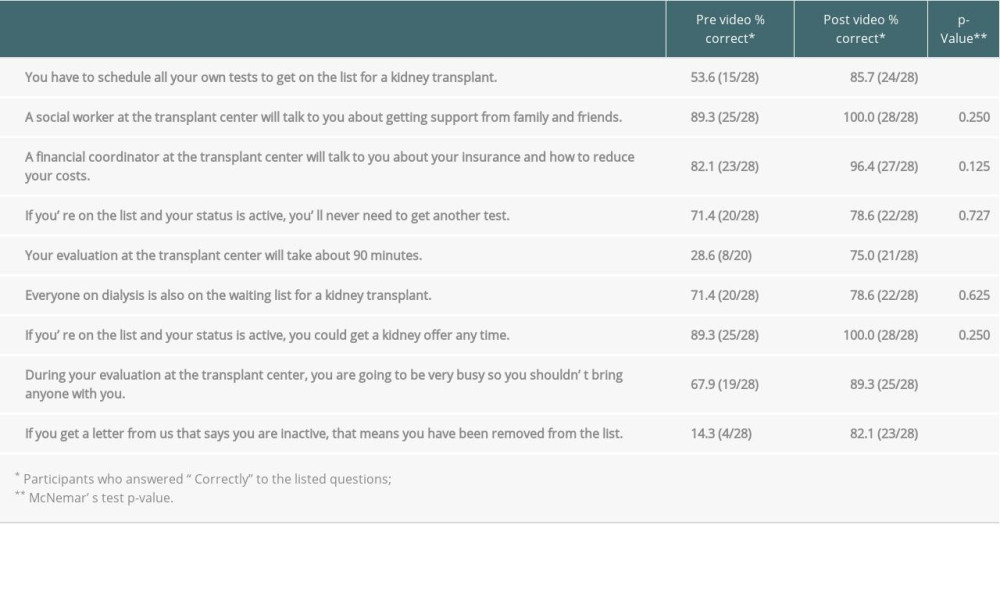

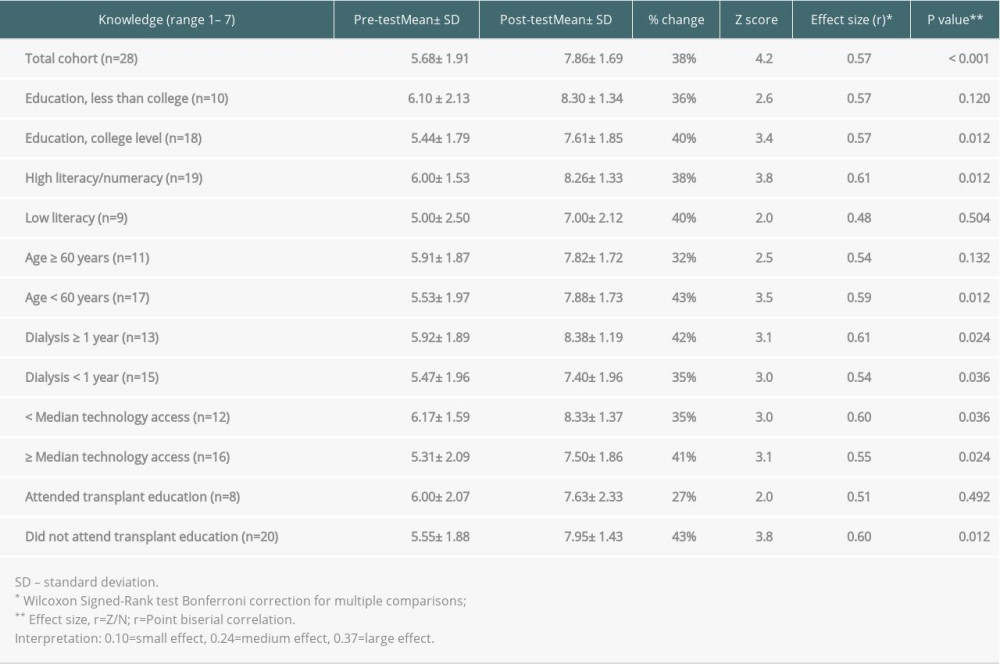

Patient knowledge gains on content about test scheduling, evaluation duration, caregiver attendance at evaluation, and inactive list status were significant (Table 6). Compared with before intervention, the mean knowledge score increased after intervention by 38% (5.7 to 7.9, P<0.001) (Table 7). For knowledge, large effect sizes were seen for the whole cohort (r=0.57) and those with age ≥60 years (r=0.54), lower educational attainment (r=0.57), lower health literacy (r=0.48), dialysis duration ≥1 year (r=0.61), less technology access (r=0.60), and absence of transplant center formal education (r=0.60).

UNDERSTANDING AND CONCERNS:

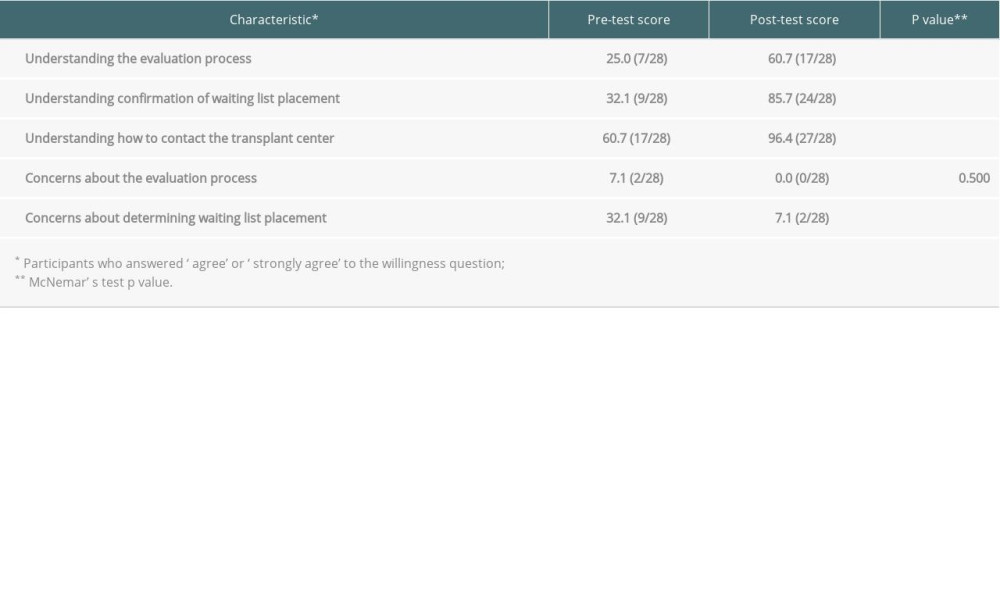

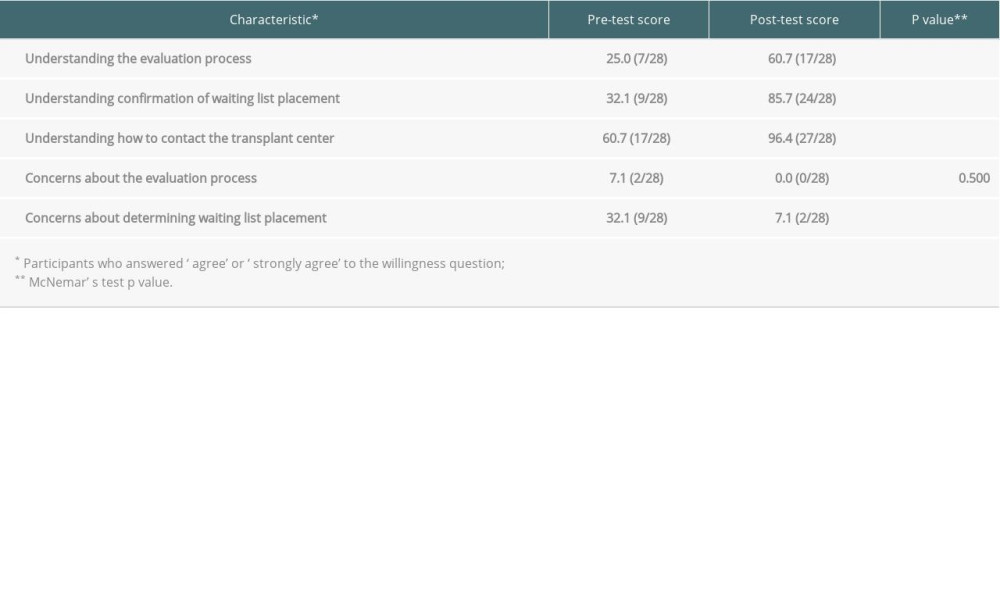

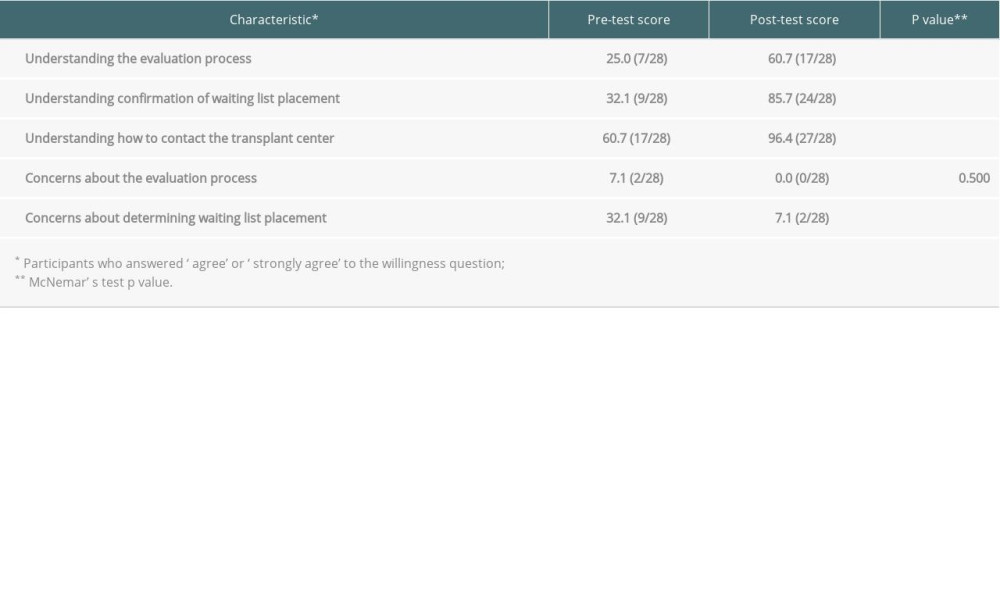

Participants reported increased understanding after video exposure about the evaluation process (25% before video to 61% after video; P=0.002), confirming waiting list placement (32% to 86%; P<0.001), and method of contacting the transplant center (61% to 96%; P=0.002). The proportion of patients who reported being concerned about the evaluation process was 7% before and 0% after (P=0.5) watching the videos. Concerns about determining waiting list placement decreased from 32% before the video to 7% after the video (P=0.039) (Table 8).

ACCEPTABILITY:

The majority of participants agreed that they felt comfortable learning from the animations (96%); the animations were easy to understand (96%) and watch (89%); the animations were interesting/engaging (93%); they could trust the information in the animations (96%); and they would personally use the animations in the future (89%) and recommend them to a friend (93%).

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

Our study has the limitation of being a single-arm, nonrandomized study with a small sample size; therefore, efficacy was not evaluated. We did not assess knowledge retention since we expect participants in the future trial to have online access with repeated viewing options. Generalizability of our results are limited in this single-center study that employed the use of email and included patients who were English-speaking and largely a non-Hispanic and White sample; however, the study population was heterogeneous in terms of sex and education level.

Conclusions

INSTITUTION WHERE WORK WAS DONE:

Work was performed at the Transplant and Kidney Care Regional Center of Excellence at Erie County Medical Center in Buffalo, NY, U.S.A.

STATEMENT:

The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit

Tables

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants. Table 2. Animation revisions based on patient input from patients, experts, and stakeholders*.

Table 2. Animation revisions based on patient input from patients, experts, and stakeholders*. Table 3. Animation title and corresponding content.

Table 3. Animation title and corresponding content. Table 4. Video title, running time, number of narrated words, number of words embedded as text, and reading level.

Table 4. Video title, running time, number of narrated words, number of words embedded as text, and reading level. Table 5. Themes and representative quotes of messages received from the animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing.

Table 5. Themes and representative quotes of messages received from the animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing. Table 6. Knowledge survey, completed by participants before and after animation viewing.

Table 6. Knowledge survey, completed by participants before and after animation viewing. Table 7. Comparison of participant knowledge scores before and after video viewing.

Table 7. Comparison of participant knowledge scores before and after video viewing. Table 8. Comparison of participant evaluation-listing understanding and concerns before and after viewing the videos.

Table 8. Comparison of participant evaluation-listing understanding and concerns before and after viewing the videos.

References

1. Neipp M, Karavul B, Jackobs S, Quality of life in adult transplant recipients more than 15 years after kidney transplantation: Transplantation, 2006; 81(12); 1640-44

2. : United States Renal Data System https://usrds.org/

3. : Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/

4. Monson RS, Kemerley P, Walczak D, Disparities in completion rates of the medical prerenal transplant evaluation by race or ethnicity and gender: Transplantation, 2015; 99(1); 236-42

5. Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting: J Am Soc Nephrol, 2009; 20(6); 1333-40

6. Sullivan C, Leon JB, Sayre SS, Impact of navigators on completion of steps in the kidney transplant process: A randomized, controlled trial: Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2012; 7(10); 1639-45

7. Kazley AS, Hund JJ, Simpson KN, Health literacy and kidney transplant outcomes: Prog Transplant, 2015; 25(1); 85-90

8. Browne T, Amamoo A, Patzer RE, Everybody needs a cheerleader to get a kidney transplant: A qualitative study of the patient barriers and facilitators to kidney transplantation in the southeastern United States: BMC Nephrol, 2016; 17(1); 108

9. Kazley AS, Simpson KN, Chavin KD, Baliga P, Barriers facing patients referred for kidney transplant cause loss to follow-up: Kidney Int, 2012; 82(9); 1018-23

10. Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Pastan S, Impact of a patient education program on disparities in kidney transplant evaluation: Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2012; 7(4); 648-55

11. Klassen AC, Hall AG, Saksvig B, Relationship between patients’ perceptions of disadvantage and discrimination and listing for kidney transplantation: Am J Public Health, 2002; 92(5); 811-17

12. Gillespie A, Hammer H, Lee J, Lack of listing status awareness: Results of a single-center survey of hemodialysis patients: Am J Transplant, 2011; 11(7); 1522-26

13. Trivedi P, Rosaasen N, Mansell H, The health-care provider’s perspective of education before kidney transplantation: Prog Transplant, 2016; 26(4); 322-27

14. Crenesse-Cozien N, Dolph B, Said M, Kidney transplant evaluation: Inferences from qualitative interviews with African American patients and their providers: J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 2019; 6(5); 917-25

15. Salter ML, Kumar K, Law AH, Perceptions about hemodialysis and transplantation among African American adults with end-stage renal disease. Inferences from focus groups: BMC Nephrol, 2015; 16; 49

16. LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: Recommendations to optimize education, access, and care: Am J Transplant, 2015; 15(4); 914-22

17. Gerity SL, Silva SG, Reynolds JM, Multimedia education reduces anxiety in lung transplant patients: Prog Transplant, 2018; 28(1); 83-86

18. Hart A, Bruin M, Chu S, Decision support needs of kidney transplant candidates regarding the deceased donor waiting list: A qualitative study and conceptual framework: Clin Transplant, 2019; 33(5); e13530

19. Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial: Am J Kidney Dis, 2013; 61(3); 476-86

20. Waterman AD, Peipert JD, An explore transplant group randomized controlled education trial to increase dialysis patients’ decision-making and pursuit of transplantation: Prog Transplant, 2018; 28(2); 174-83

21. Patzer RE, Paul S, Plantinga L, A randomized trial to reduce disparities in referral for transplant evaluation: J Am Soc Nephrol, 2017; 28(3); 935-42

22. Patzer RE, McPherson L, Basu M, Effect of the iChoose Kidney decision aid in improving knowledge about treatment options among transplant candidates: A randomized controlled trial: Am J Transplant, 2018; 18(8); 1954-65

23. Basu M, Petgrave-Nelson L, Smith KD, Transplant center patient navigator and access to transplantation among high-risk population: A randomized, controlled trial: Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2018; 13(4); 620-27

24. Mayer RE, Moreno R, Animation as an aid to multimedia learning: Educ Psychol Rev, 2002; 14(1); 87-99

25. Leiner M, Handal G, Williams D, Patient communication: A multidisciplinary approach using animated cartoons: Health Educ Res, 2004; 19(5); 591-95

26. Slater M, Rouner D, Entertainment education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion: Commun Theory, 2002; 12(2); 173-91

27. Reigeluth CM, In search of a better way to organize instruction: The Elaboration Theory: J Instr Dev, 1979; 2(3); 8-15

28. Bandura A, Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change: Psychol Rev, 1977; 84(2); 191-215

29. Lewis L, Dolph B, Said M, Enabling conversations: African American patients; changing perceptions of kidney transplantation: J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 2019; 6(3); 536-45

30. Jones J, Rosaasen N, Taylor J, Health literacy, knowledge, and patient satisfaction before kidney transplantation: Transplant Proc, 2016; 48(8); 2608-14

31. Ben-Sira Z, Latent fear-arousing potential of fear-moderating and fear-neutral health promoting information: Soc Sci Med E, 1981; 15(2); 105-12

32. Kayler LK, Dolph B, Seibert R, Development of the living donation and kidney transplantation information made easy (KidneyTIME) educational animations: Clin Transplant, 2020; 34(4); e13830

33. Gordon EJ, Reddy E, Gil S, Culturally competent transplant program improves Hispanics’ knowledge and attitudes about live kidney donation and transplant: Prog Transplant, 2014; 24(1); 56-68

34. Medlock MC, Wixon D, Terrano M, Using the RITE method to improve products; A definition and a case study. in Usability Professionals Association: Orlando, 2002

35. Keller M, Seibert R, Feeley T, Kayler L, Patient-informed design of an educational website on living kidney donation

36. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population: J Gen Intern Med, 2008; 23(5); 561-66

37. McGillicuddy JW, Weiland AK, Frenzel RM, Patient attitudes toward mobile phone-based health monitoring: Questionnaire study among kidney transplant recipients: J Med Internet Res, 2013; 15(1); e6

38. Kayler L, Dolph B, Cleveland C, Educational animations to inform transplant candidates about deceased donor kidney options: An efficacy randomized trial: Transplantation Direct, 2020; 6(7); e575

39. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ, Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation: J Exp Psychol Gen, 2012; 141(1); 2-18

40. Patzer RE, Pastan SO, Measuring the disparity gap: Quality improvement to eliminate health disparities in kidney transplantation: Am J Transplant, 2013; 13(2); 247-48

41. Stukas AA, Dew MA, Switzer GE, PTSD in heart transplant recipients and their primary family caregivers: Psychosomatics, 1999; 40(3); 212-21

42. Rainer JP, Thompson CH, Lambros H, Psychological and psychosocial aspects of the solid organ transplant experience – a practice review: Psychotherapy (Chicago), 2010; 47(3); 403-12

43. Browne T, The relationship between social networks and pathways to kidney transplant parity: Evidence from black Americans in Chicago: Soc Sci Med, 2011; 73(5); 663-67

44. Balhara KS, Kucirka LM, Jaar BG, Segev DL, Disparities in provision of transplant education by profit status of the dialysis center: Am J Transplant, 2012; 12(11); 3104-10

45. Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Xiao H, Education strategies in dialysis centers associated with increased transplant wait-listing rates: Transplantation, 2020; 104(2); 335-42

Tables

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants. Table 2. Animation revisions based on patient input from patients, experts, and stakeholders*.

Table 2. Animation revisions based on patient input from patients, experts, and stakeholders*. Table 3. Animation title and corresponding content.

Table 3. Animation title and corresponding content. Table 4. Video title, running time, number of narrated words, number of words embedded as text, and reading level.

Table 4. Video title, running time, number of narrated words, number of words embedded as text, and reading level. Table 5. Themes and representative quotes of messages received from the animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing.

Table 5. Themes and representative quotes of messages received from the animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing. Table 6. Knowledge survey, completed by participants before and after animation viewing.

Table 6. Knowledge survey, completed by participants before and after animation viewing. Table 7. Comparison of participant knowledge scores before and after video viewing.

Table 7. Comparison of participant knowledge scores before and after video viewing. Table 8. Comparison of participant evaluation-listing understanding and concerns before and after viewing the videos.

Table 8. Comparison of participant evaluation-listing understanding and concerns before and after viewing the videos. Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants. Table 2. Animation revisions based on patient input from patients, experts, and stakeholders*.

Table 2. Animation revisions based on patient input from patients, experts, and stakeholders*. Table 3. Animation title and corresponding content.

Table 3. Animation title and corresponding content. Table 4. Video title, running time, number of narrated words, number of words embedded as text, and reading level.

Table 4. Video title, running time, number of narrated words, number of words embedded as text, and reading level. Table 5. Themes and representative quotes of messages received from the animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing.

Table 5. Themes and representative quotes of messages received from the animations about kidney transplant evaluation and listing. Table 6. Knowledge survey, completed by participants before and after animation viewing.

Table 6. Knowledge survey, completed by participants before and after animation viewing. Table 7. Comparison of participant knowledge scores before and after video viewing.

Table 7. Comparison of participant knowledge scores before and after video viewing. Table 8. Comparison of participant evaluation-listing understanding and concerns before and after viewing the videos.

Table 8. Comparison of participant evaluation-listing understanding and concerns before and after viewing the videos. In Press

18 Mar 2024 : Original article

Does Antibiotic Use Increase the Risk of Post-Transplantation Diabetes Mellitus? A Retrospective Study of R...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943282

20 Mar 2024 : Original article

Transplant Nephrectomy: A Comparative Study of Timing and Techniques in a Single InstitutionAnn Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942252

28 Mar 2024 : Original article

Association Between FEV₁ Decline Rate and Mortality in Long-Term Follow-Up of a 21-Patient Pilot Clinical T...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942823

02 Apr 2024 : Original article

Liver Transplantation from Brain-Dead Donors with Hepatitis B or C in South Korea: A 2014-2020 Korean Organ...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943588

Most Viewed Current Articles

05 Apr 2022 : Original article

Impact of Statins on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Living-Donor Liver TransplantationDOI :10.12659/AOT.935604

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935604

12 Jan 2022 : Original article

Risk Factors for Developing BK Virus-Associated Nephropathy: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study of ...DOI :10.12659/AOT.934738

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e934738

22 Nov 2022 : Original article

Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipient...DOI :10.12659/AOT.937988

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e937988

15 Mar 2022 : Case report

Combined Liver, Pancreas-Duodenum, and Kidney Transplantation for Patients with Hepatitis B Cirrhosis, Urem...DOI :10.12659/AOT.935860

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935860