14 November 2023: Original Paper

Evolution of Liver Transplantation Over the Last 2 Decades Based on a Single-Center Experience of 300 Cases

Akihiko Soyama1ABCDEF*, Takanobu HaraDOI: 10.12659/AOT.941796

Ann Transplant 2023; 28:e941796

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Over the past 2 decades, there have been many medical advances in the field of liver transplantation. We conducted this study to evaluate the changes in liver transplantation over the last 2 decades.

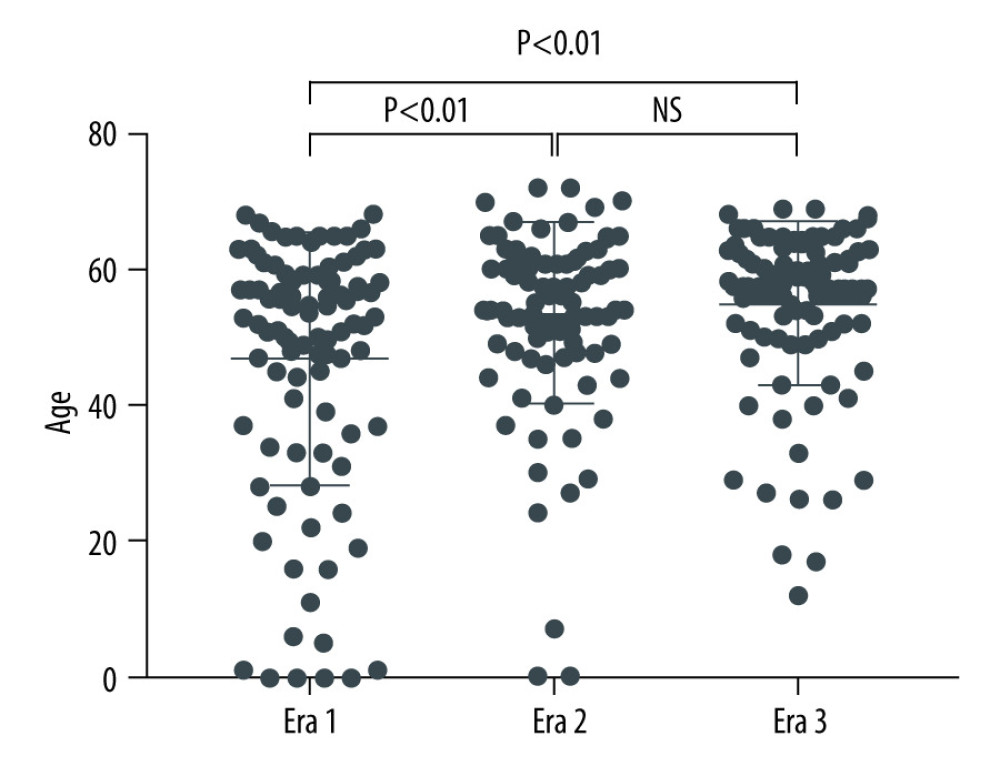

MATERIAL AND METHODS: Three hundred cases of liver transplantation encountered between 1997 and 2019 in Nagasaki University Hospital were divided into 3 groups: Era 1 (cases no. 1-100), Era 2 (cases no. 101-200), and Era 3 (cases no. 201-300). Several items were compared among the groups.

RESULTS: There were no cases of deceased-donor liver transplantation in Era 1, 1 case in Era 2, and 12 cases in Era 3. The proportion of virus-related disease was significantly lower in Era 3 compared to other eras. In contrast, the proportion of alcoholic liver cirrhosis was significantly higher in Era 3 (27%) than Era 1 (7%) and Era 2 (10%) (P<0.01). In Era 1, the right lobe was selected most frequently, but in Eras 2 and 3, the left lobe was more frequently selected.

CONCLUSIONS: The evolution of the treatment and the transplant system in Japan is clearly reflected in the indications and types of donors for liver transplantation, even at a single center in Japan.

Keywords: Liver Transplantation, Living Donors, Liver Cirrhosis, Tissue and Organ Procurement

Background

Since the first living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) was performed in Japan in 1989, more than 9000 have been performed to date [1]. The first LDLT at Nagasaki University Hospital was performed in 1997, in a pediatric patient, and the first deceased-donor liver transplantation (DDLT) was performed in 2011. Since 2004, when LDLT for adults became covered by national healthcare insurance in Japan, the number of adult LDLTs has increased significantly [2]. While the number of LDLTs was still about 10 per year at most until 10 years after the enforcement of the Organ Transplant Law, since the revision of the law in 2009, the number of brain-dead liver transplants has increased significantly [3].

In 2019, the number of liver transplants performed at Nagasaki University Hospital reached 300. During the 20 years that have lapsed since the first procedure was performed in 1997, in addition to the above-mentioned social factors of insurance coverage and revision of the Organ Transplant Law, there have been a number of medical advances, including the advent of new treatments for primary diseases, such as antiviral therapy, the establishment of ABO blood group-incompatible transplantation, and the development of immunosuppressive agents. In 2009, when the 100th of the 300 liver transplants was performed, the law on organ donation involving brain-dead donors was amended. In 2014, when the 200th liver transplant was performed, treatment with interferon-free direct-acting antivirals for HCV was clinically introduced. Since the milestones of the 100th and 200th of the 300 liver transplants performed at our institution coincided with events that have had significant impacts on liver transplantation care, we decided to divide the 300 cases by year into 3 groups of 100 cases each and examine their clinical features.

This report summarizes the indications, surgical procedures, and outcomes of 300 cases of liver transplantation performed at Nagasaki University Hospital and clarifies the trends over time.

Material and Methods

STATISTICAL ANALYSES:

A chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical values and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for continuous variables. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables among the 3 groups. The survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared in each group by the log-rank test. A

Results

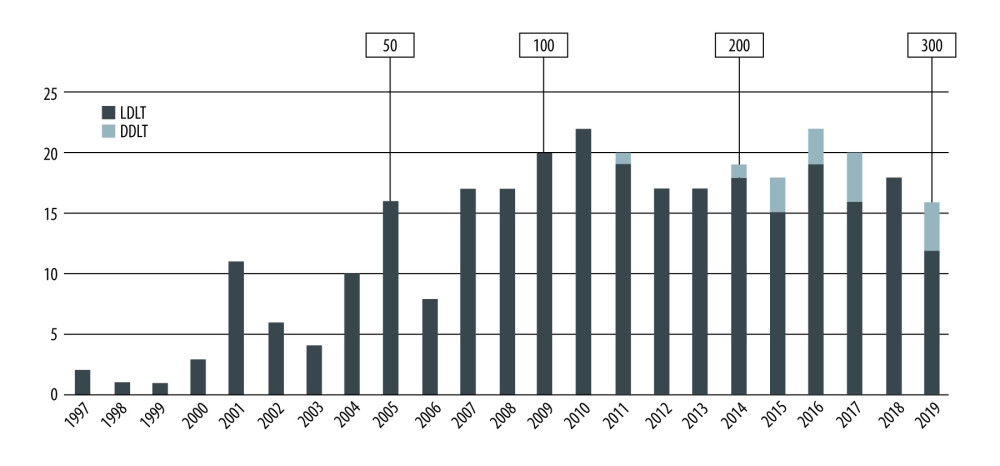

TYPE OF DONOR (BRAIN-DEAD DONOR/LIVING DONOR):

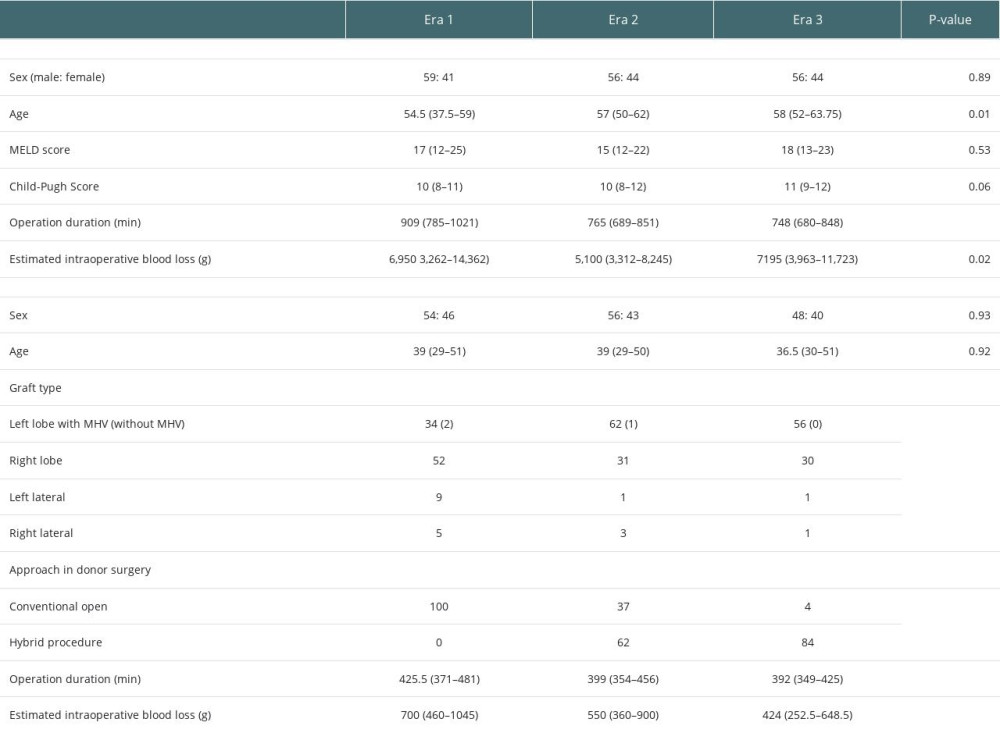

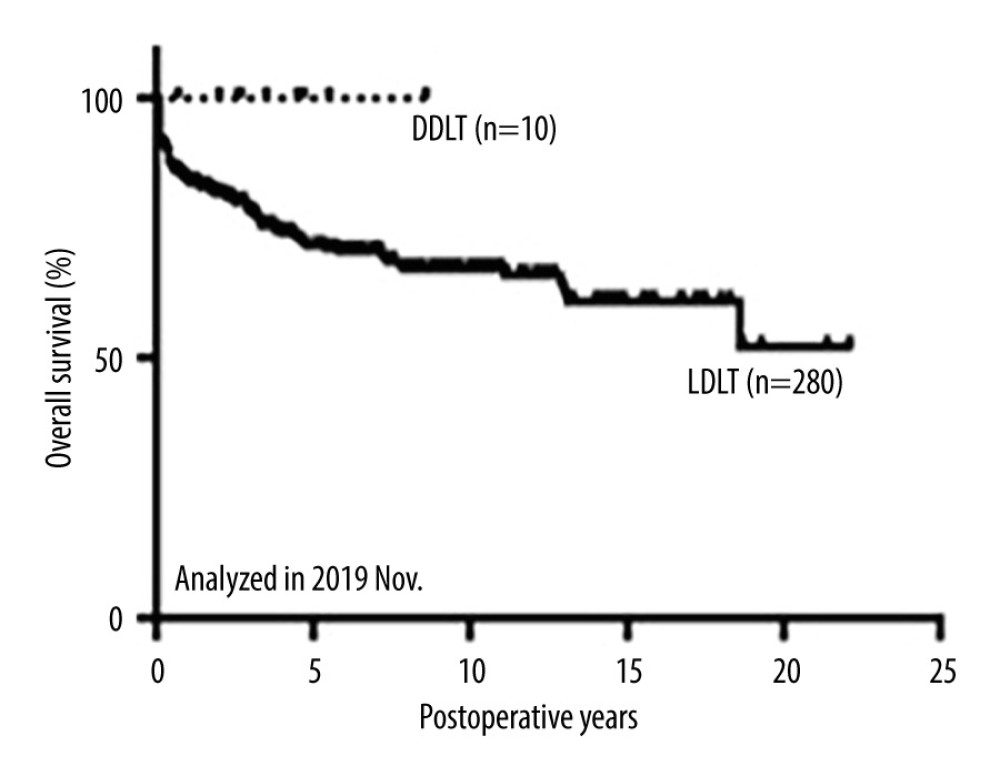

The first DDLT was performed in 2011. Since then, 13 patients have undergone DDLT from brain-dead donors among 300 liver transplantations. There were no cases of DDLT in Era 1, 1 case in Era 2, and 12 cases in Era 3 (Figure 1).

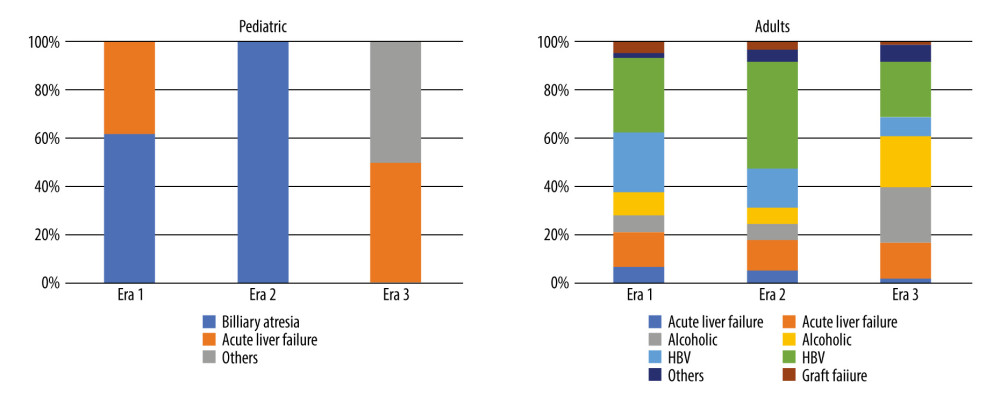

INDICATION:

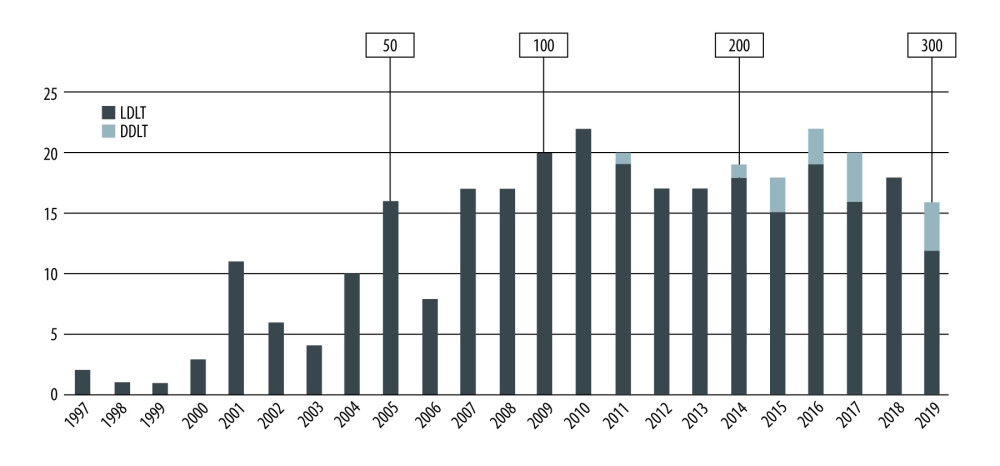

Among 300 patients, 16 pediatric patients and 284 adult patients were included. Figure 2 shows the indications of liver transplantation in each era. In pediatric patients, BA was the most common indication in Era 1 (64%) and Era 2 (100%). The proportion of acute liver failure was 36% in Era 1 and 50% in Era 2. The proportion of virus-related disease, such as liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV), was significantly lower in Era 3 compared with other eras (P<0.01, 56% in Era 1, 61% in Era 2, and 32% in Era 3). When we examined HBV and HCV separately, we found no difference between Eras 1 and 2 for the proportion of HBV (25% in Era 1, 16% in Era 2), but Era 3 (8%) showed a significant decrease of the proportion of HBV compared with Eras 1 and 2. On the other hand, the proportion of HCV increased significantly from Era 1 (31%) to Era 2 (44%), and then decreased significantly from Era 2 to Era 3 (23%). In contrast, the proportion of alcoholic liver cirrhosis was significantly higher in Era 3 (23%) than in Era 1 (7%) and Era 2 (8%) (P<0.01).

No significant changes in cholestatic disease or acute liver failure were recognized. The proportion of non-viral and non-alcoholic cirrhosis was significantly higher in Era 3 compared to Era 2, possibly due to an increase in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (

The proportion of recipients complicated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) did not show any significant difference among the eras (45% in Era 1, 42% in Era 2, and 28% in Era 3).

Ten patients underwent retransplantation (3.3%): 7 underwent LDLT and 3 underwent DDLT.

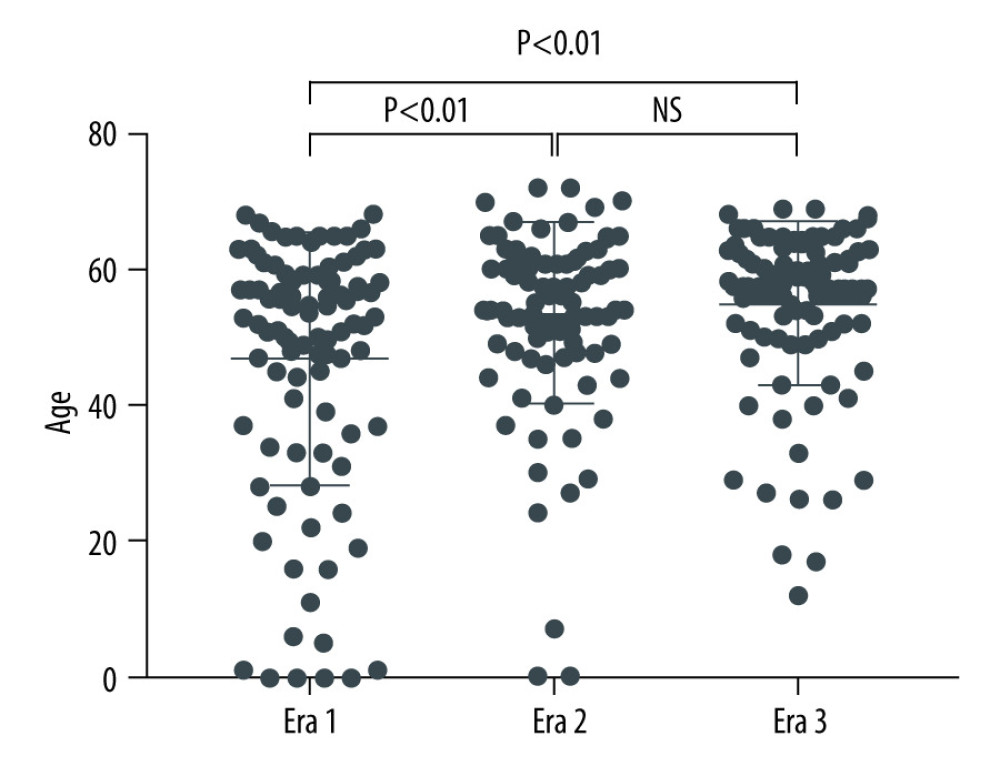

RECIPIENT AGE:

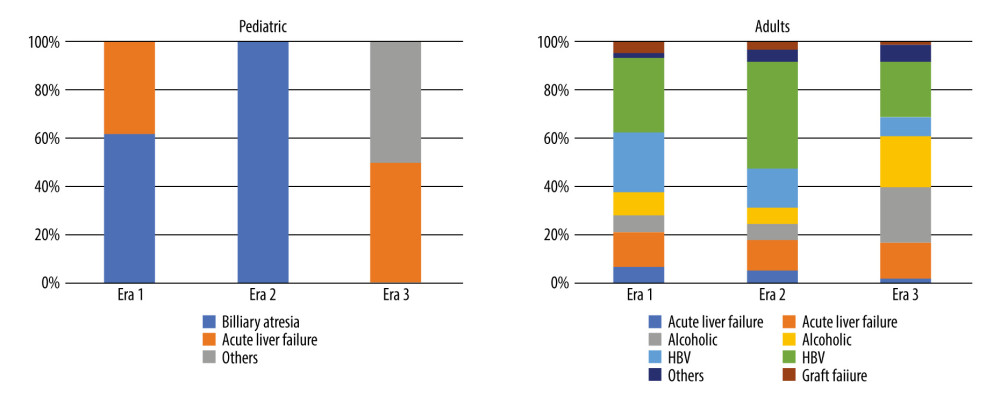

Table 1 and Figure 3 shows the distribution of recipient age in each era. Recipient age was significantly older in Eras 2 and 3 than in Era 1. The median ages (years old; range) were 54.5 years (6–68 years) in Era 1, 57 years (2–71 years) in Era 2, and 58 (12–69 years) in Era 3.

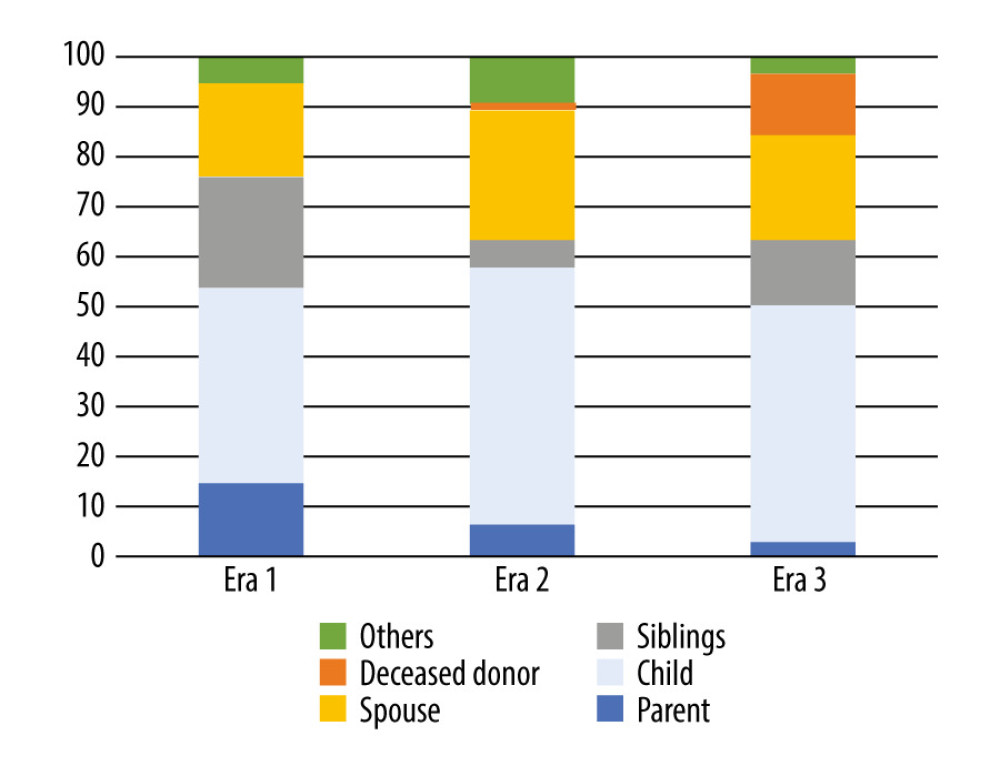

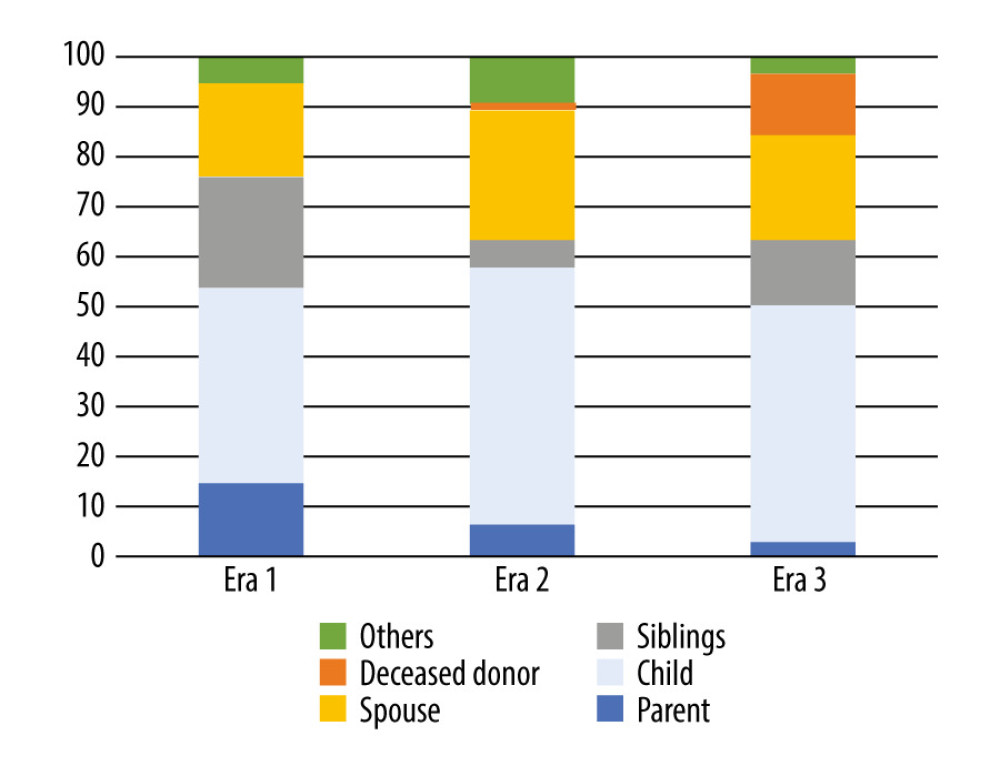

DONOR RELATIONSHIPS TO RECIPIENTS:

Figure 4 shows donor relationships to recipients. The proportion of parents was significantly lower in Eras 2 and 3 than in Era 1 (P<0.01). The proportions of other relationships did not differ markedly among the eras.

TYPE OF GRAFTS:

Figure 5 shows the type of grafts used in LDLT. In Era 1, the right lobe was selected most frequently, but in Eras 2 and 3, the left lobe was more frequently selected, and the frequency was about twice that of the right lobe.

APPROACH TO DONOR SURGERY (OPEN PROCEDURE/HYBRID PROCEDURE):

The concept of minimally invasive surgery with the laparoscopic procedure was adopted in 2010. The hybrid technique we established involves laparoscopic mobilization and hepatectomy through a midline incision. The details of the hybrid technique have been reported elsewhere [4,5]. The hybrid technique was started in Era 2, and most of the donors underwent hepatectomy with this technique in Eras 2 and 3 (Figure 6). Over time, there was a significant decrease in operative duration and estimated blood loss (Table 1).

ABO COMPATIBILITY:

The first LDLT with ABO incompatibility was performed in 2002. Since then, 52 ABO-incompatible (ABO-i) LDLTs have been performed. There were no marked differences in the proportion of ABO-i LDLT among the eras: 15 in Era 1, 18 in Era 2, and 19 in Era 3.

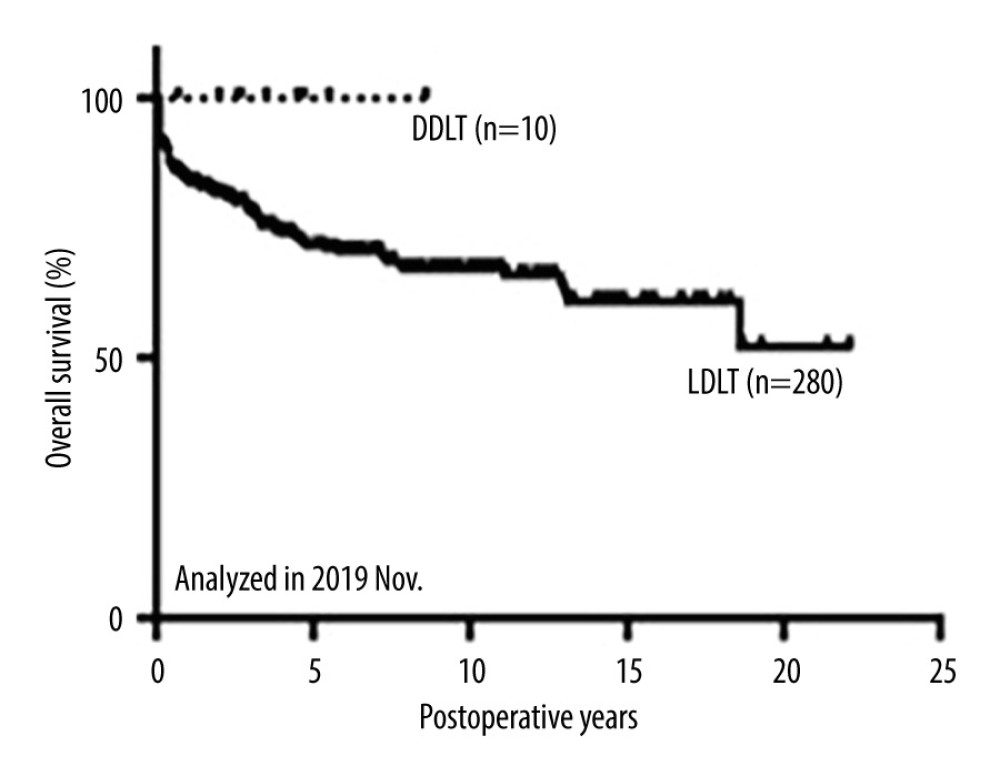

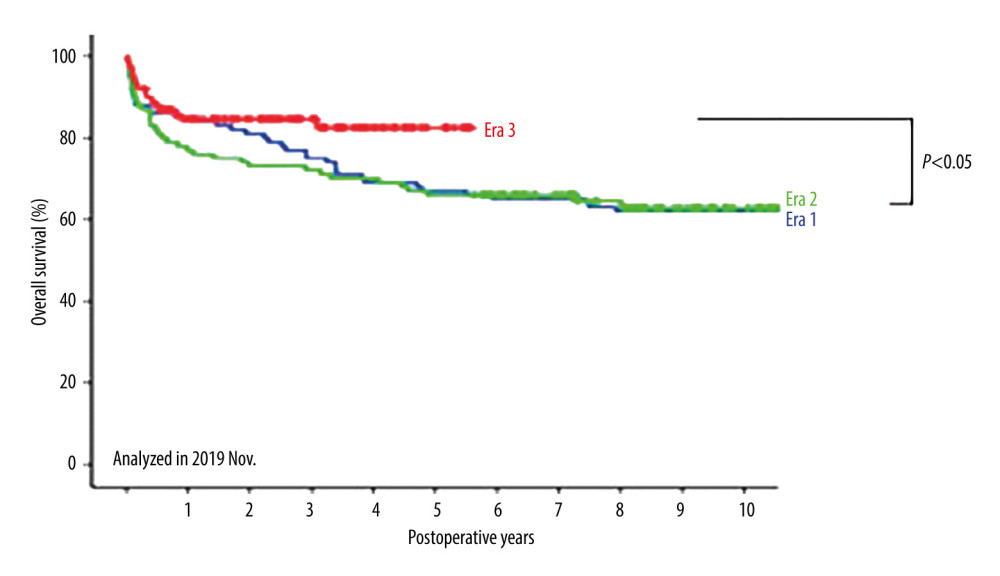

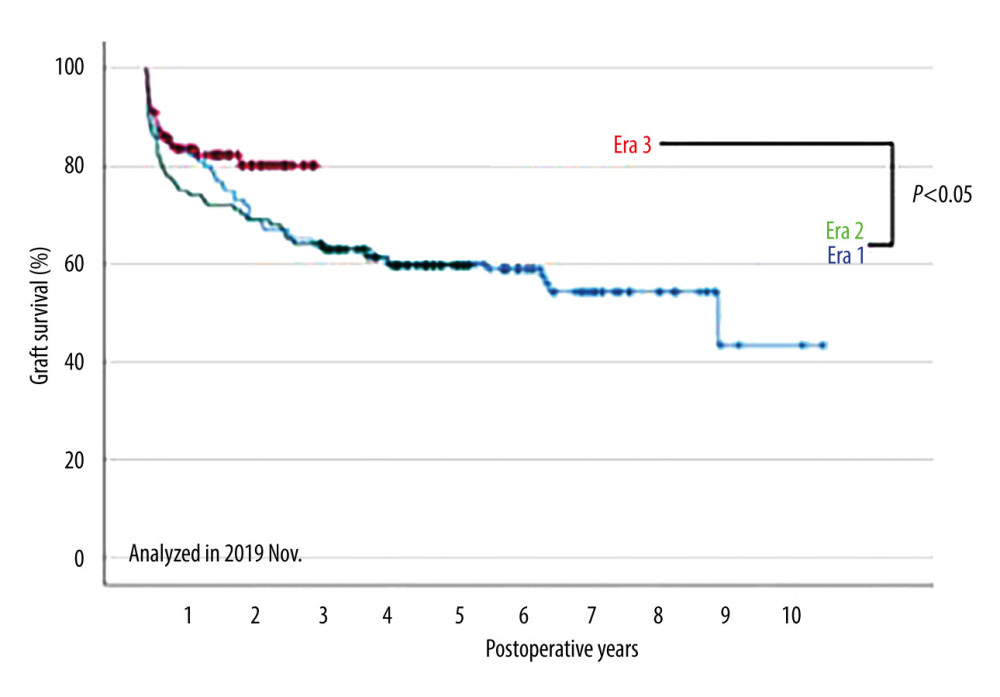

SURVIVAL RATE:

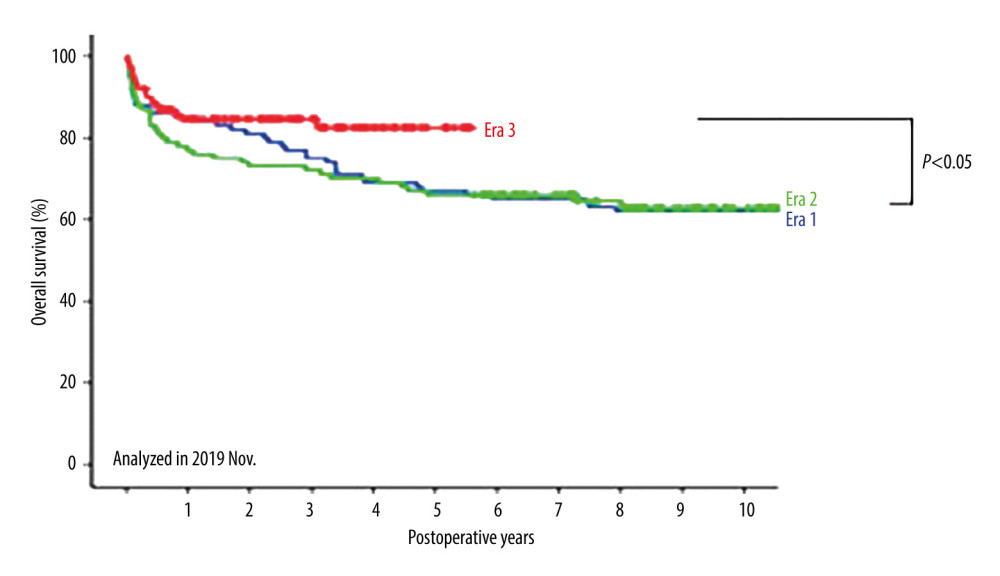

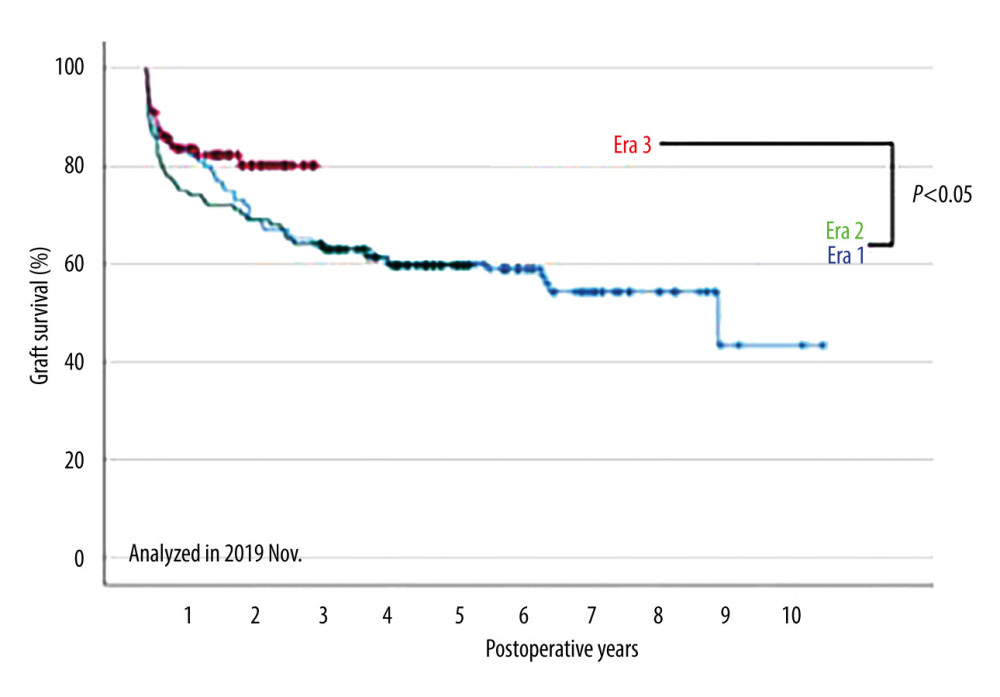

Figure 5 shows the overall survival rates of patients who underwent primary liver transplantation (n=290); the overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 82%, 76%, and 69%, respectively, in adults, and 80%, 73%, and 67%, respectively, in pediatric patients. Figures 6 and 7 show a comparison of the overall survival and graft survival rates among the 3 eras. Graft loss resulted in retransplantation or death. Although the follow-up period of Era 3 was relatively short, the long-term outcomes of patients who underwent transplants in Eras 1 and 2 (which have comparable follow-up periods) were not significantly different.

Discussion

Over the last 2 decades, the development of treatment for primary diseases of liver transplant recipients, such as antiviral therapy and improvement of immunosuppression therapy, seems to have influenced the indication and outcomes of liver transplantation [1,6–9]. The results of the current study show significant changes in the indications of liver transplantation, even in a single center.

By Era 2, it had already become possible to control HBV after liver transplantation, but we experienced difficult cases due to postoperative HCV relapse until the middle of Era 2 [2]. However, with the development of direct-acting antivirals, complicated cases with HCV relapse in Era 3 were significantly decreased. Significant differences were observed in the proportion of HCV as an indication among eras in this study. This phenomenon is considered to be due to the expansion of indication to adult cases from Era 1 to Era 2, followed by a decrease in HCV indication from Era 2 to Era 3 due to the establishment of viral therapy with DAA.

In contrast, although there was no marked difference in the numbers of HCC cases among the eras, the indications for both brain-dead liver transplantation and LDLT changed from the conventional Milan criteria to the 5-5-500 criteria in 2019 and 2020, respectively [10,11]. With the expansion of indications, the proportion of HCC cases may increase. As the number of liver transplants for viral cirrhosis has decreased, the number of cases of alcoholic and NAFLD-related cirrhosis has increased. The prevention of alcohol relapse or NAFLD recurrence seems to be the key management approach during mid- and long-term follow-up to achieve favorable long-term outcomes [12].

The ratio of liver transplantation with donations from brain-dead donor, donor after cardiac death, and LDLT varies by region and country [3]. The revision of the Organ Transplant Law in 2010 significantly changed the environment for organ donation in Japan. Before the amendment, there were about 10 DDLTs per year, but in 1999, nearly 90 brain-dead liver transplants were performed. The organ allocation rule was changed in 2019, and an approach involving the evaluation of the medical urgency based on the MELD score was adopted. Although the number of procedures is still small compared to other countries, further expansion of brain-dead liver transplantation is expected in the future.

Although the number of brain-dead liver transplants has increased with time, more than 90% of liver transplants are still LDLT. In LDLT, the safety of living donors is of utmost importance. We have established a living-donor advocacy team in our hospital [13]. In addition to ensuring procedure safety, a reduction in invasiveness in donor surgery has also been pursued [14]. The introduction of laparoscopic procedures to donor hepatectomy is an epoch-making surgical advancement in the field of LDLT [15]. We established a hybrid technique including laparoscopic mobilization of the liver with subsequent vascular management and parenchymal transection under direct vision through an upper-midline incision [4,5]. In addition to comparable perioperative outcomes to conventional open procedures, donors with upper-midline incisions in the hybrid procedure showed fewer wound-related complications, such as numbness or discomfort, than donors with a right subcostal incision [16].

Recently, Rana et al reported the long-term survival after liver transplantation over 3 decades [17] – the 1-year survival was 66%, which improved to 92% in 2015. In contrast, there have been no appreciable improvements in long-term survival following liver transplantation among 1-year survivors. The authors concluded that malignancy, infection, and long-term administration of immunosuppression are the most common causes of death. At our center, we conduct regular screening of recipients for early detection and treatment of de novo cancer. We have also reported the effects of chronic kidney disease and sarcopenia as factors that affect the long-term prognosis [18,19]. Efforts by multidisciplinary teams are essential for improving long-term results after liver transplantation.

This study has some limitations. It was a retrospective study, and groups were set up for every 100 cases; hence, the patients were not assigned to groups based on the direct impact of therapeutic and surgical methods that have been developed over the past 20 years. During the study period, there were epoch-making events in transplantation medicine, such as changes in legislation, the introduction of DAA for HCV, and the introduction of blood group-incompatible transplants, as well as the introduction of laparoscopic techniques in donor surgery. However, the direct impact of those events was not examined in this study.

Conclusions

Medical advances and the revision of the transplant system in Japan over the last 20 years have been clearly reflected in various aspects of transplant management, such as changes in treatment indications in a single institution and an increase in brain-dead donor transplantations. However, no significant differences in overall survival were noted among eras. Therefore, to improve treatment outcomes and perioperative care, the establishment of medium- to long-term follow-up strategies to prevent the development of recurrence of primary disease, de novo cancer, metabolic diseases, and chronic rejection are extremely important.

Figures

Figure 1. Trends in liver transplantation at Nagasaki University Hospital.

Figure 1. Trends in liver transplantation at Nagasaki University Hospital.  Figure 2. Indications for liver transplantation.

Figure 2. Indications for liver transplantation.  Figure 3. Distribution of recipient age.

Figure 3. Distribution of recipient age.  Figure 4. Donor relationship to recipient.

Figure 4. Donor relationship to recipient.  Figure 5. Overall survival of patients after primary liver transplantation.

Figure 5. Overall survival of patients after primary liver transplantation.  Figure 6. Comparison of overall survival among the 3 eras.

Figure 6. Comparison of overall survival among the 3 eras.  Figure 7. Comparison of graft survival among the 3 eras.

Figure 7. Comparison of graft survival among the 3 eras. References

1. Umeshita K, Eguchi S, Egawa H, Liver transplantation in Japan: Registry by the Japanese Liver Transplantation Society: Hepatol Res, 2019; 49; 964-80

2. Eguchi S, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, Evolution of living donor liver transplantation over 10 years: Experience of a single center: Surg Today, 2008; 38; 795-800

3. Soyama A, Eguchi S, Egawa H, Liver transplantation in Japan: Liver Transpl, 2016; 22; 1401-7

4. Soyama A, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, Standardized less invasive living donor hemihepatectomy using the hybrid method through a short upper midline incision: Transplant Proc, 2012; 44; 353-55

5. Eguchi S, Soyama A, Hara T, Standardized hybrid living donor hemihepatectomy in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: Liver Transpl, 2018; 24; 363-68

6. Ueda Y, Ikegami T, Soyama A, Simeprevir or telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for recurrent hepatitis C after living-donor liver transplantation: A Japanese multicenter experience: Hepatol Res, 2016; 46; 1285-93

7. Ikegami T, Ueda Y, Akamatsu N, Asunaprevir and daclatasvir for recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation: A Japanese multicenter experience: Clin Transplant, 2017; 31; ctr.13109

8. Ueda Y, Ikegami T, Akamatsu N, Treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir without ribavirin for 12 weeks is highly effective for recurrent hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection after living donor liver transplantation: A Japanese multicenter experience: J Gastroenterol, 2017; 52; 986-91

9. Miuma S, Miyaaki H, Soyama A, Utilization and efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir for treating hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation: Hepatol Res, 2018; 48; 1045-54

10. Shimamura T, Akamatsu N, Fujiyoshi M, Expanded living-donor liver transplantation criteria for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma based on the Japanese nationwide survey: The 5-5-500 rule – a retrospective study: Transpl Int, 2019; 32; 356-68

11. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis: N Engl J Med, 1996; 334; 693-99

12. Miyaaki H, Miuma S, Taura N, Risk factors and clinical course for liver steatosis or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after living donor liver transplantation: Transplantation, 2019; 103; 109-12

13. Eguchi S, Soyama A, Nagai K, The donor advocacy team: A risk management program for living organ, tissue, and cell transplant donors: Surg Today, 2017; 47; 980-85

14. Shirabe K, Eguchi S, Okajima H, Current status of surgical incisions used in donors during living related liver transplantation – a nationwide survey in Japan: Transplantation, 2018; 102; 1293-99

15. Soubrane O, Eguchi S, Uemoto S, Minimally invasive donor hepatectomy for adult living donor liver transplantation: an international, multi-institutional evaluation of safety, efficacy and early outcomes: Ann Surg, 2020; 275(1); 166-74

16. Imamura H, Soyama A, Takatsuki M, Self-assessment of postoperative scars in living liver donors: Clin Transplant, 2013; 27; E605-10

17. Rana A, Ackah RL, Webb GJ, No gains in long-term survival after liver transplantation over the past three decades: Ann Surg, 2019; 269; 20-27

18. Inoue Y, Soyama A, Takatsuki M, Does the development of chronic kidney disease and acute kidney injury affect the prognosis after living donor liver transplantation?: Clin Transplant, 2016; 30; 518-27

19. Pravisani R, Soyama A, Isola M, Chronological changes in skeletal muscle mass following living-donor liver transplantation: An analysis of the predictive factors for long-term post-transplant low muscularity: Clin Transplant, 2019; 33; e13495

Figures

Figure 1. Trends in liver transplantation at Nagasaki University Hospital.

Figure 1. Trends in liver transplantation at Nagasaki University Hospital. Figure 2. Indications for liver transplantation.

Figure 2. Indications for liver transplantation. Figure 3. Distribution of recipient age.

Figure 3. Distribution of recipient age. Figure 4. Donor relationship to recipient.

Figure 4. Donor relationship to recipient. Figure 5. Overall survival of patients after primary liver transplantation.

Figure 5. Overall survival of patients after primary liver transplantation. Figure 6. Comparison of overall survival among the 3 eras.

Figure 6. Comparison of overall survival among the 3 eras. Figure 7. Comparison of graft survival among the 3 eras.

Figure 7. Comparison of graft survival among the 3 eras. In Press

28 Mar 2024 : Original article

Association Between FEV₁ Decline Rate and Mortality in Long-Term Follow-Up of a 21-Patient Pilot Clinical T...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942823

02 Apr 2024 : Original article

Liver Transplantation from Brain-Dead Donors with Hepatitis B or C in South Korea: A 2014-2020 Korean Organ...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943588

02 Apr 2024 : Original article

Effect of Dexmedetomidine Combined with Remifentanil on Emergence Agitation During Awakening from Sevoflura...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943281

03 Apr 2024 : Review article

Alternative Therapies in Transplantology as a Promising Perspective in MedicineAnn Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943387

Most Viewed Current Articles

05 Apr 2022 : Original article

Impact of Statins on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Living-Donor Liver TransplantationDOI :10.12659/AOT.935604

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935604

12 Jan 2022 : Original article

Risk Factors for Developing BK Virus-Associated Nephropathy: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study of ...DOI :10.12659/AOT.934738

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e934738

22 Nov 2022 : Original article

Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipient...DOI :10.12659/AOT.937988

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e937988

15 Mar 2022 : Case report

Combined Liver, Pancreas-Duodenum, and Kidney Transplantation for Patients with Hepatitis B Cirrhosis, Urem...DOI :10.12659/AOT.935860

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935860