23 January 2024: Original Paper

Preliminary Evaluation of 2 Patient-Centered Educational Animations About Kidney Transplant Complications

Sydney Johnson1BCE, Anne Solbu12BCE, Renee Cadzow3CE, Thomas H. Feeley4E, Maria Keller12C, Liise K. Kayler12ACE*DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942611

Ann Transplant 2024; 29:e942611

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Fear of kidney transplant complications and incomplete information can lower transplant acceptance and preparedness. Our group developed 2 patient-centered educational animated videos on common kidney transplant complications to complement a previously developed video-based curriculum intended to promote kidney transplant access.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: We preliminarily evaluated the 2 animated educational videos at a single center using mixed methods. We conducted a before-and-after single group study with 22 patients after kidney transplantation to measure the videos’ acceptability and feasibility to improve patient knowledge, understanding, and concerns of kidney transplant complications. Concurrently, we individually interviewed 12 patients before kidney transplantation about their perceptions of the 2 videos and analyzed the data thematically.

RESULTS: Knowledge of kidney transplant complications increased 10% (7.82 to 8.59, P=0.002) from before to after video viewing. Large effect size increases for knowledge were found for different strata of age, race, and health literacy. The mean total score for perceived understanding of kidney transplant complications increased after video exposure by 7% (mean 2.48 to 2.66, P=0.184). There was no change in kidney transplant concern scores from before to after video viewing (mean 1.70 to 1.70, P=1.00). After video viewing, all patients reported positive ratings on comfort watching, understanding, and engaging. Three themes of patient perceptions emerged: (1) messages received as intended, (2) felt informed, and (3) scared but not deterred.

CONCLUSIONS: Two animated educational videos about kidney transplant complications were well received and promise to positively impact individuals’ knowledge and understanding, without raising excessive concerns.

Keywords: Education, Health Communication, Kidney Transplantation, Postoperative Complications

Background

Over 500 000 people are treated with long-term dialysis in the United States. A kidney transplant generally extends and improves lives relative to dialysis [1], yet less than 20% of patients are on the kidney transplant waitlist [2]. Although this is multifactorial in cause, a commonly cited reason for the low prevalence of waitlisting is individual concern for kidney transplant complications. Concerns include undergoing major surgery, not waking from general anesthesia, physical complications, medication adverse effects, allograft failure or organ rejection, and fear of the unknown [3–12]. Surprise or unpreparedness for transplant complications continuing after kidney transplant is increasingly reported in the literature [13–15]. Misperceptions, fear of the unknown, and incomplete information can lower candidate acceptance of kidney transplant and transplant preparedness [15–17].

Prior research has shown that patient knowledge, or health literacy, is associated with transplant access [18–20] and outcomes [20,21]. However, the extent to which previous educational approaches explained transplant risks is unknown. Explaining medical risks to lay individuals is challenging and can lead to confusion or misinterpretation of the message, despite patient-centric education [22]. Video has been suggested as useful for introductory learning by kidney transplant recipients [23]. Animated video in particular is an impactful educational medium that can promote understanding and reach of the information, with the added benefit of lowering fear [24–26]. Our research group recently developed a curriculum of educational animations (named KidneyTIME) to promote kidney transplant access, which has been previously described [27]. The need for additional information regarding kidney transplant complications was noted during development studies with patients [28] and interviews with lay caregivers [15]. Specifically, patients and families assessing kidney transplant educational materials felt unprepared for transplant complications and desired more information about kidney transplant risks, specifically in video format [15,28]. Therefore, our research team developed a pair of videos about common kidney transplant complications to improve the balance of the content within the KidneyTIME curriculum and to improve kidney transplant preparedness.

In this paper, we report preliminary quantitative evidence of the videos’ acceptability and feasibility, and we qualitatively evaluated patients’ perception of the content. The results can assist other transplant knowledge translators to design successful teaching-learning styles for health communication about medical risk.

Material and Methods

BACKGROUND:

Two animated videos about common kidney transplant complications were previously developed by our group in an iterative, evidence-based, stakeholder-engaged, human-centered design process, underpinned by major concepts from multiple theories, as described below.

The educational content for the videos was derived from literature review, formative research, and clinical expertise [4,15]. Key concerns included (1) complications that occur commonly after kidney transplant (edema, gastrointestinal upset, incisional fluid drainage, allograft rejection, delayed graft function), (2) recipient behaviors to enhance recovery (leg elevation, eating before pill consumption, patient-provider communication), and (3) care actions of providers (dressing changes, medication adjustment, home healthcare nurse, allograft biopsy, dialysis). The content also suggested a trigger for remembering medication. One video presentation was instructional (expository), and the other was in the form of an illustrated story (narrative) about a male kidney transplant recipient who goes on a weekend camping trip and realizes he has forgotten to bring his transplant medications. He decides to take an extra dose upon returning home and finds out that he has developed allograft rejection. The narrative-based video provided the opportunity to center the message on medication understanding rather than solely immunosuppressant importance [16].

The content was transformed into 2 scripts by a transplant surgeon (LK). A preliminary video prototype was developed and then reviewed and refined by a health communication expert, a medical anthropologist, a behavioral researcher, and a community advisory board of 3 kidney transplant candidates and recipients, 2 care partners, and a dialysis social worker. Textual changes were made mainly to simplify and order sentences. The content and visuals were targeted to a multi-cultural population and used some images from the KidneyTIME video curriculum [27].

Self-Efficacy Theory was operationalized by using characters inclusive of the intended audience, demonstrating behaviors, providing gain-framed messages in an emotionally reassuring way, and showing healthcare provider support [27]. The content was written using health communication principles (plain language, active voice, conversational style, concise sentences) and was organized using elaboration theory (core concept, other facts added “just in time”) [29,30]. Animation design was informed by the cognitive theory of multimedia learning [31], which describes how to time visual animation effects to match the voice-over to facilitate information processing and use meaningful images, signaling, and limited text.

The senior author oversaw video production, working closely with the artist and the animator. The design features of the videos included 2-dimensional schematic images, minimal animation, and optimization for small screen viewing. The videos were 3.41 and 3.28 min long.

PRESENT STUDY:

This descriptive study included 3 components. (1) We developed surveys to test knowledge, understanding, and concerns related to the content of 2 previously developed educational animated videos about common kidney transplant complications. (2) We conducted a preliminary quantitative evaluation of the videos with an uncontrolled, single-group, pretest-posttest design at the transplant center. (3) We used qualitative methods to evaluate the content of the videos. This study was Institutional Review Board approved by the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

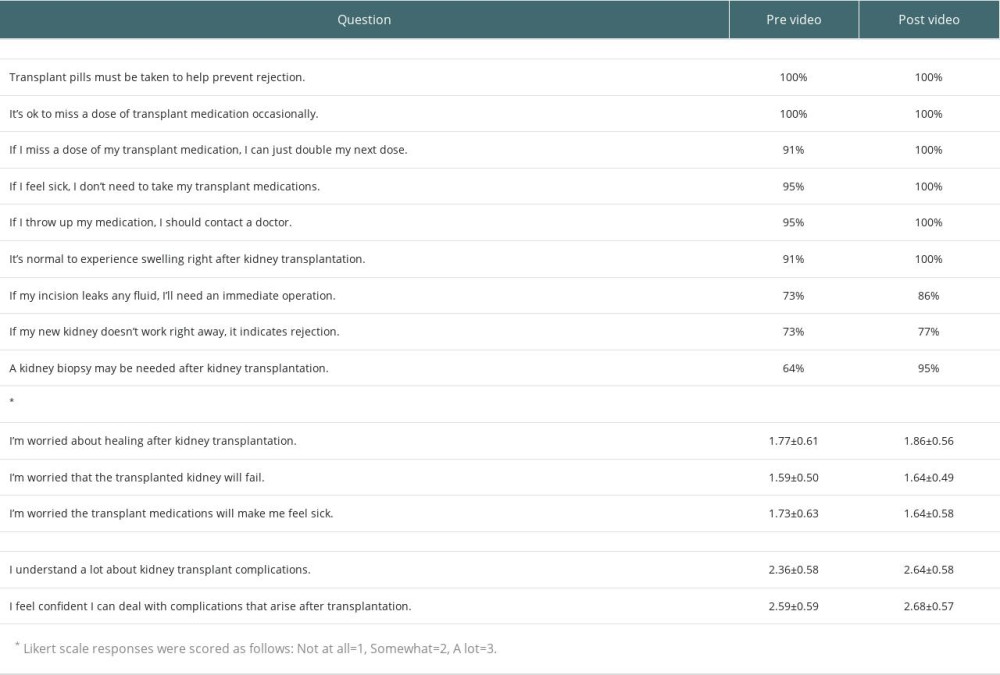

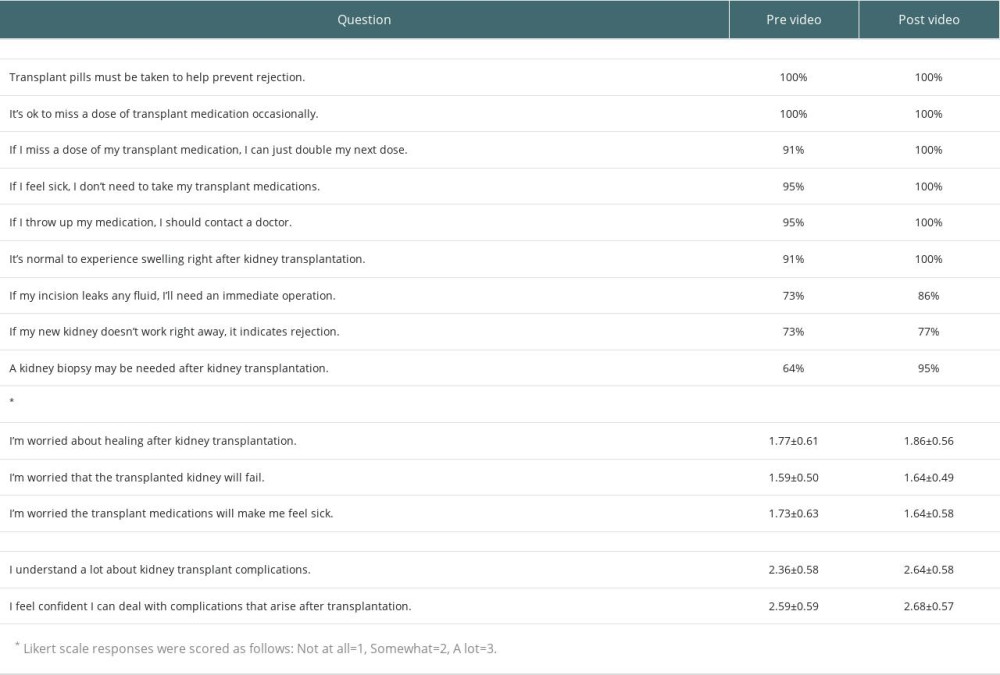

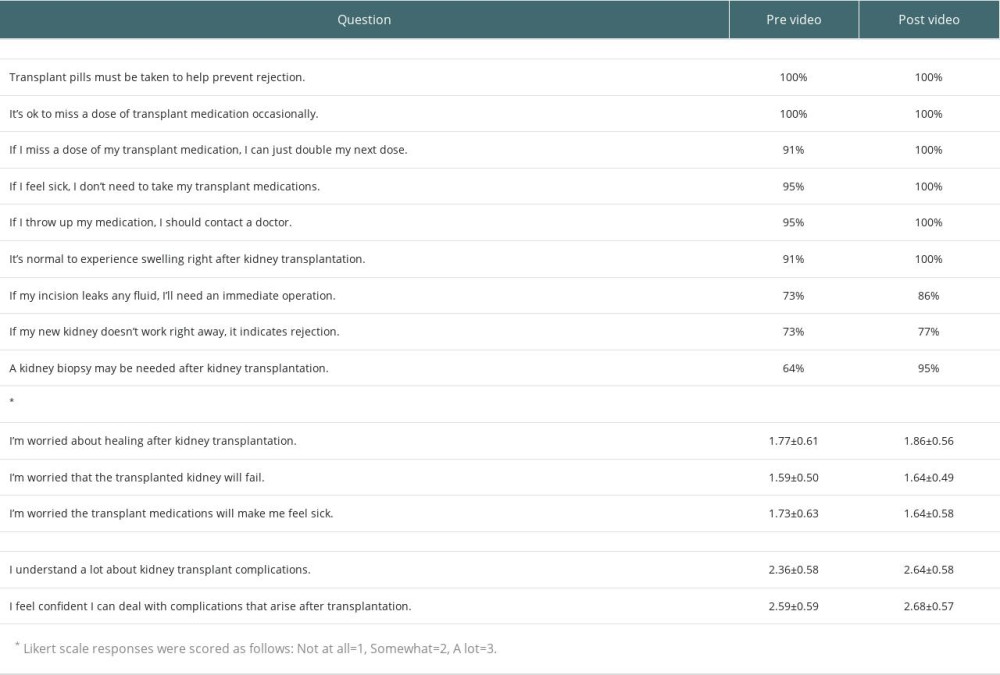

COMPONENT 1: DEVELOPMENT OF SURVEYS: The survey questions were drafted and vetted by the researchers and then piloted with 7 kidney transplant recipients. A medical student trained in qualitative techniques used the questionnaires to conduct cognitive interviews. Respondents were asked about item relevance and clarity. Their responses were recorded with field notes and used to modify the questions. Table 1 shows each question.

COMPONENT 2: FEASIBILITY AND ACCEPTABILITY TESTING OF THE VIDEOS:

Between April 2023 and July 2023, the final 2 videos were evaluated with recent kidney transplant recipients at Erie County Medical Center in New York. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 18 years of age or older, English speaking, and within 1 month of kidney transplantation.

Consecutive kidney transplant recipients meeting the inclusion criteria were approached in their hospital room or clinic room by a medical student. Following completed paper-based consent, patients answered 11 questions about their sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, race, employment status, education level, marital status, total annual household income), medical status (dialysis vintage, prior kidney transplant), and health literacy, as well as measures of kidney transplant complication knowledge (9 items, true/false), understanding (2 items, Likert scale: not at all/somewhat/a lot), and concerns (3 items, Likert scale: not at all/somewhat/a lot). After survey completion, the patients were shown the 2 videos on an iPad, followed by identical survey questions to the pre-tests, with the sociodemographic question replaced with video acceptability questions (11 items, 4-point Likert scale strongly agree/disagree) that were developed by the researchers. The respondents were compensated with a $25.00 Visa debit card.

COMPONENT 3: QUALITATIVE EVALUATION OF THE VIDEOS: The 12 cognitive interviews were conducted via telephone between April 2023 and July 2023. Participants were patients before transplantation who had been randomized to the control group in a trial of the KidneyTIME intervention, which included an exit interview upon trial completion [27]. Those who were first to schedule an interview were included until data saturation was achieved (no longer yielded new information). Sessions were conducted via telephone or videoconference using an interview guide to explore what content of the videos was useful or in what manner the patients were impacted. All sessions were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed for accuracy.

SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION:

Knowledge of kidney transplant perioperative complications before and after the study with 24 participants was determined to provide a power of 80% to detect at minimum a 0.60 standardized effect size using a single-group

DATA ANALYSIS:

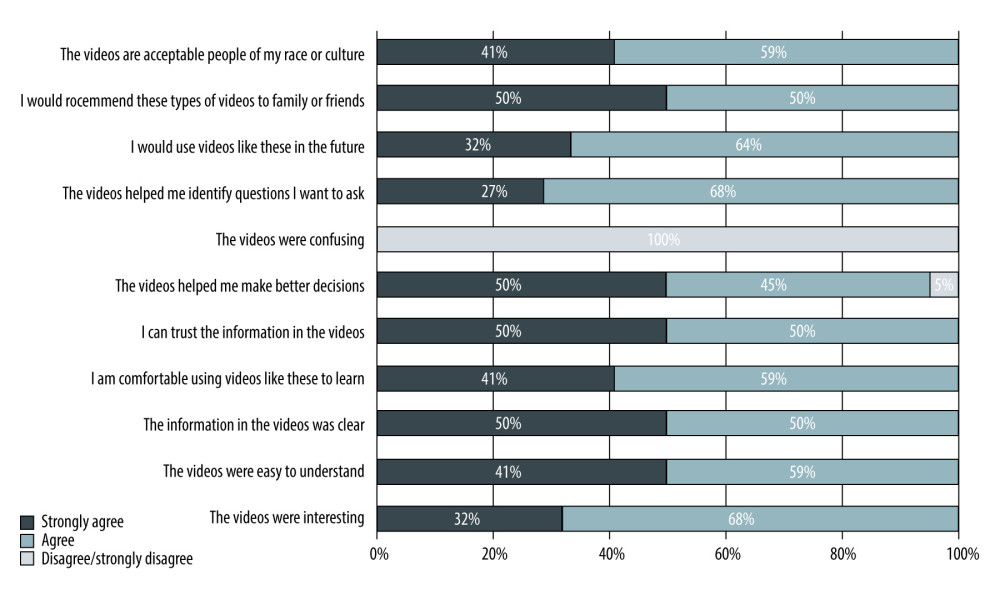

Quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Frequencies were computed for all categorical variables and means with standard deviation for continuous variables. To measure effect size, the point biserial correlation [32] was calculated as the test statistic (z score) divided by the square root of the total observations (effect size, r=Z/√N) with 0.1, 0.2, and 0.32 corresponding to small, medium, and large effects, respectively. The z score was derived from the Wilcoxon signed-rank test given that the data were non-parametric. Knowledge scores were calculated by summing the number of correct answers. Higher scores of Likert scales reflect greater understanding and concerns. Participants’ animation acceptability was provided using a bar graph (Figure 1). Statistical significance was considered a 2-tailed alpha of 0.05.

Transcriptions from individual interviews were independently read by each member of the qualitative research team: a medical anthropologist, a communication expert, a medical student, and a transplant surgeon, who agreed on a coding framework to extract the meaningful content of patient perceptions of the videos. The data were coded by AS and SJ and uploaded into Dedoose Version 9.0.17 for thematic analysis. Patterned responses were collated, grouped, and developed into themes by RC and discussed and revised by the qualitative research team. Data saturation was achieved, in that no new data was identified in the last 3 transcripts.

Results

VIDEO EVALUATION QUANTITATIVE STUDY:

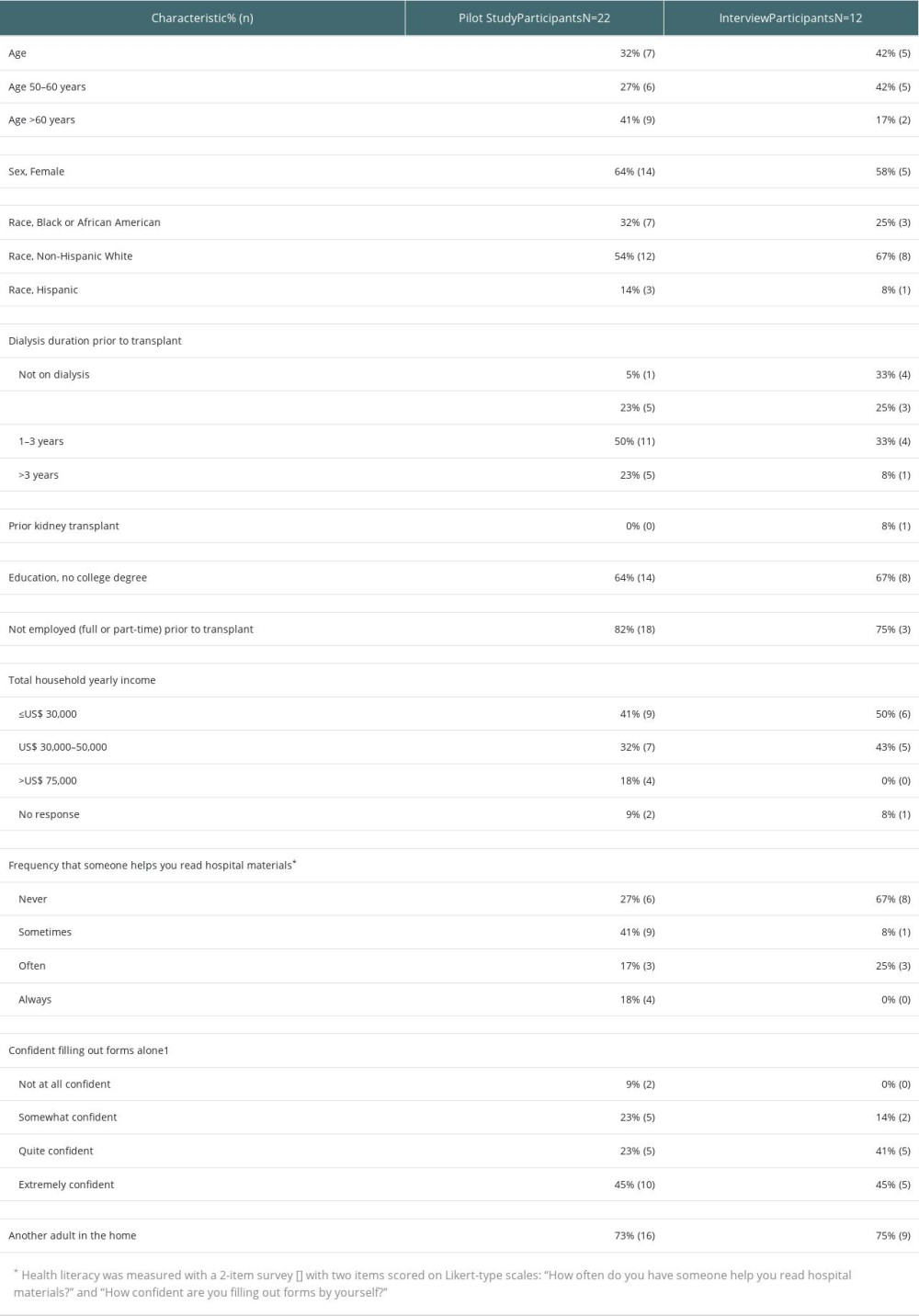

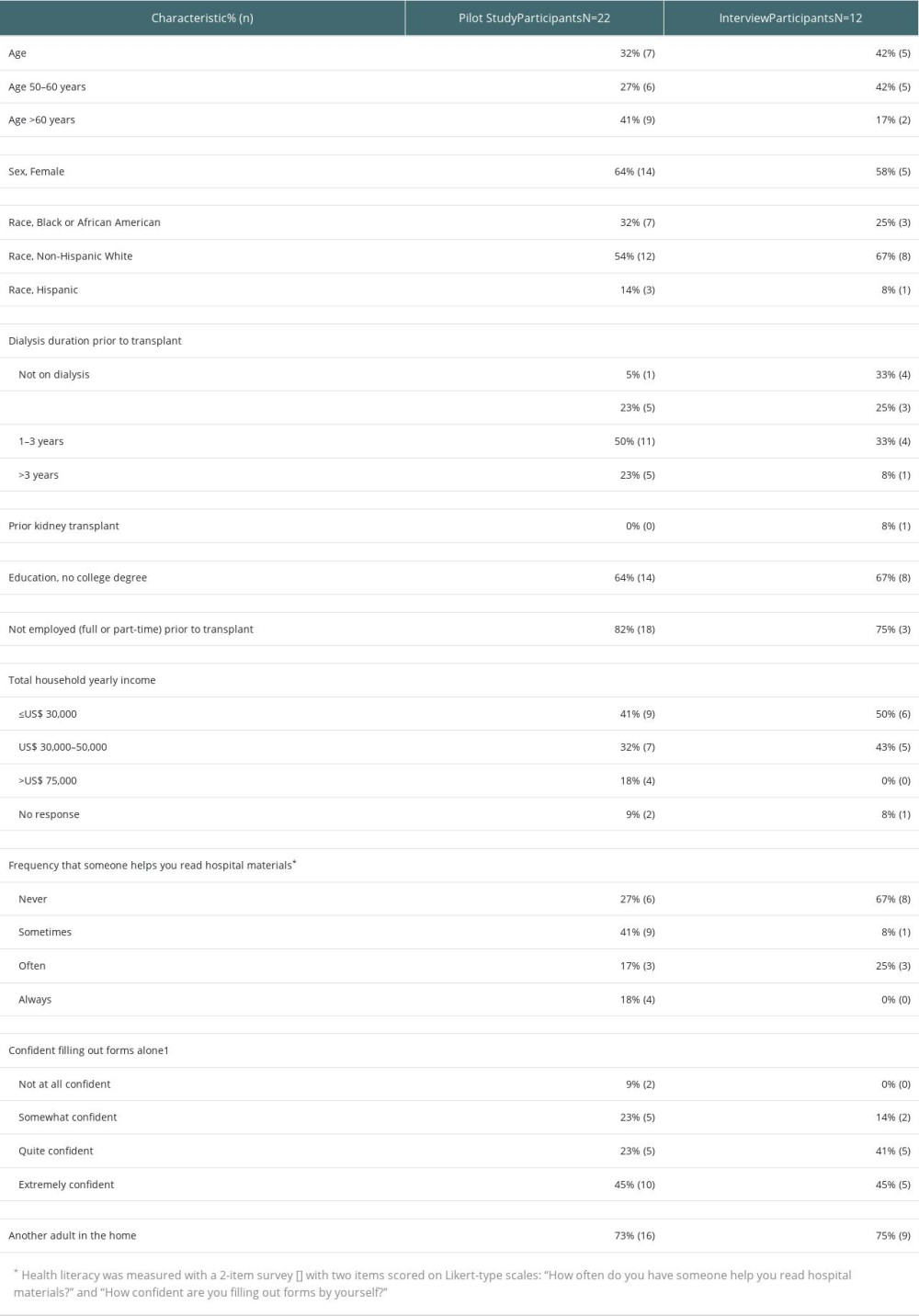

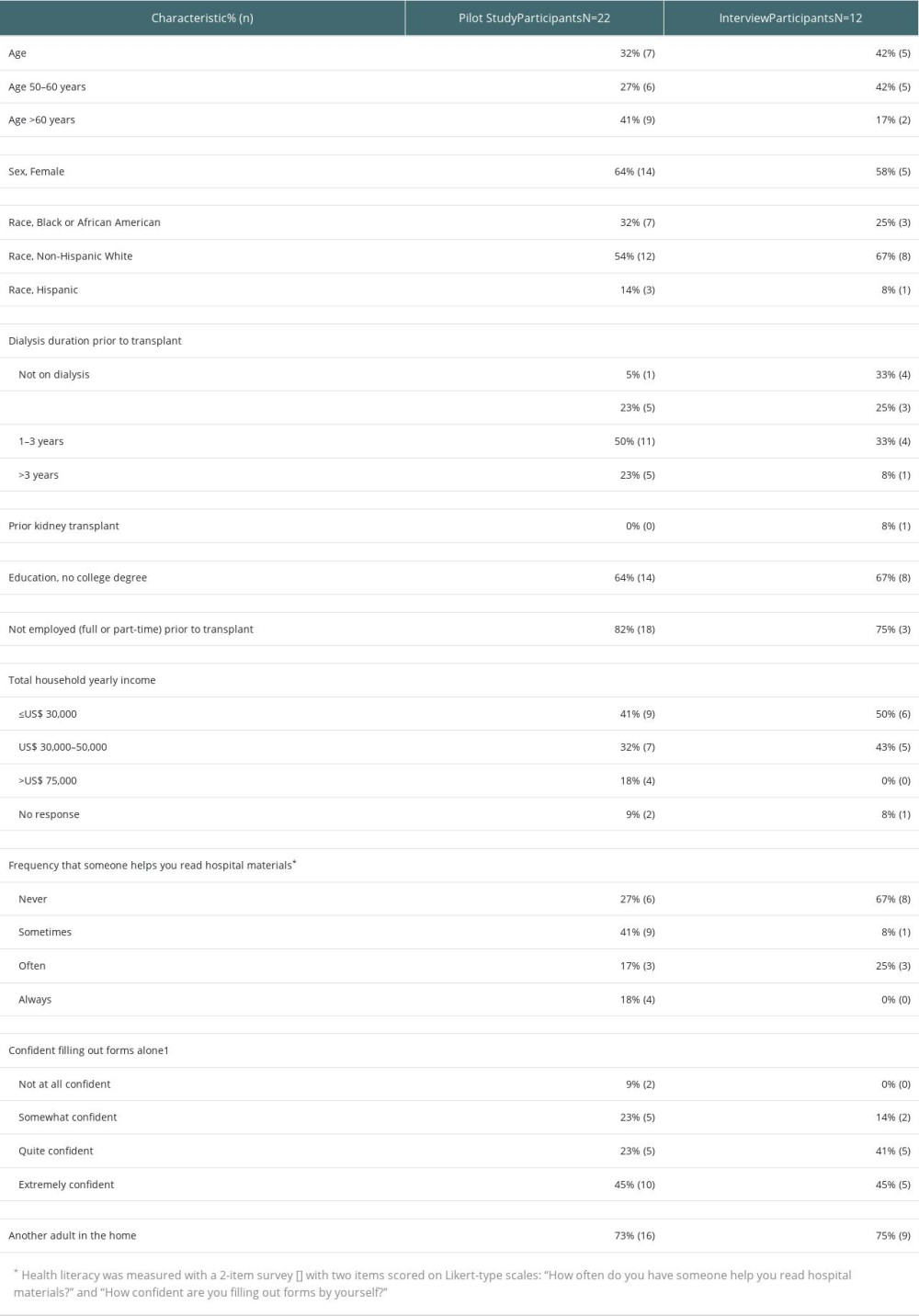

We invited 25 kidney transplant recipients during the enrollment period, and 22 participated in the study; 17 were in the hospital before discharge, and the remainder were in the transplant clinic. Most patients in the total sample were aged 50 years or older; 64% were women; 82% were not employed; 41% had an annual household income <$30,000; and 32% were African American. Approximately one-third of patients reported “often” or “always” using help from someone to read hospital materials and feeling “not at all” or “somewhat” confident filling out forms alone (Table 2).

KNOWLEDGE OF KIDNEY TRANSPLANT COMPLICATIONS:

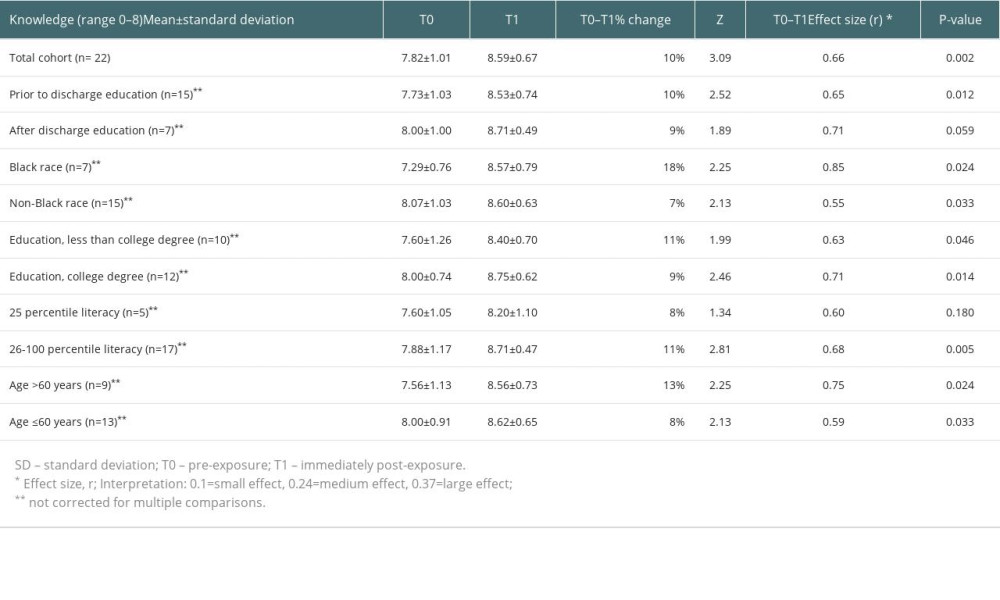

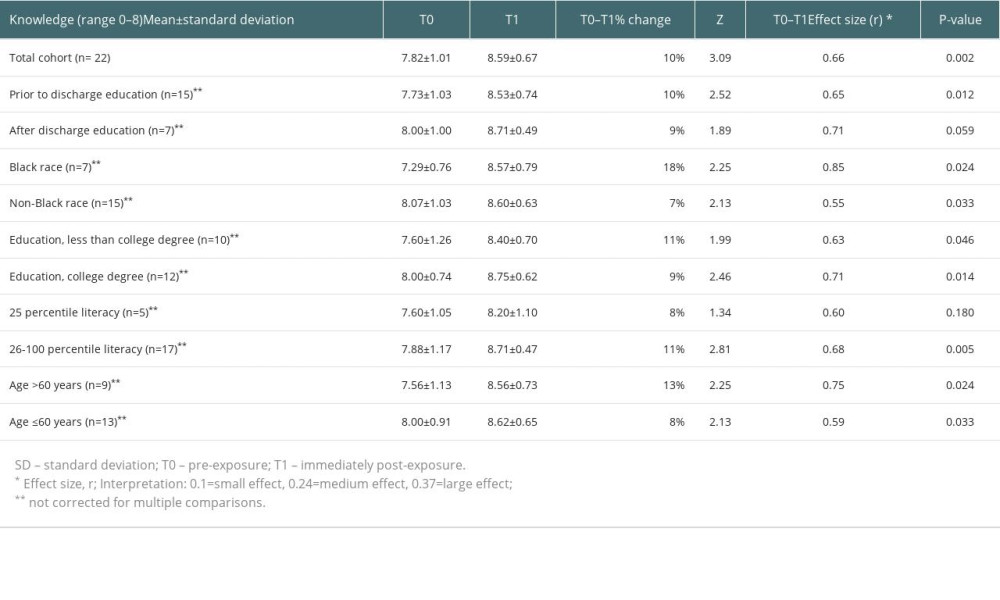

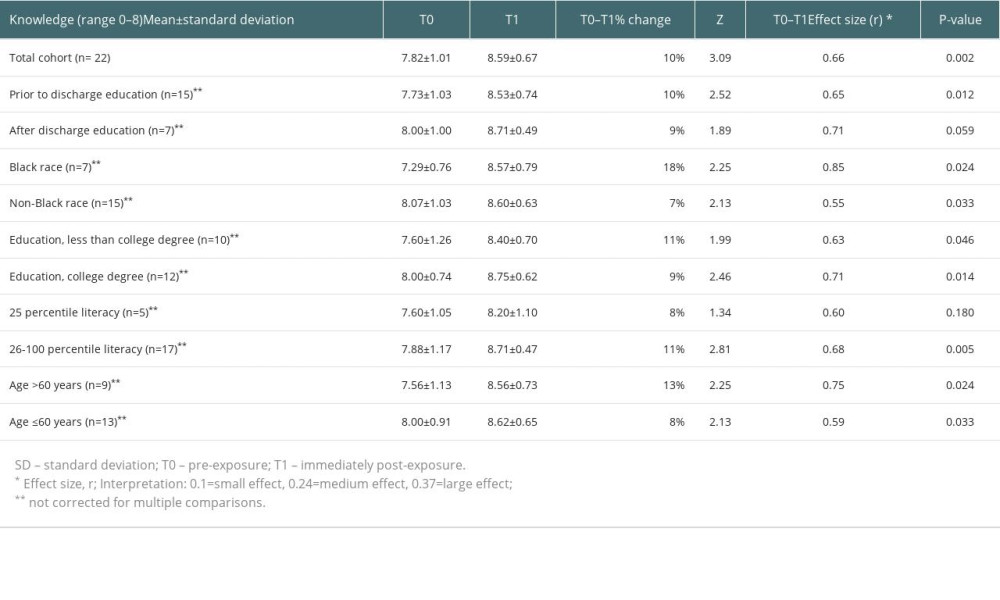

Relative to pre-animation, the mean total knowledge score increased after viewing by 10% (mean 7.82 to 8.59, P=0.002). Knowledge large effect sizes were seen for the entire cohort (r=0.66) and in the context of age ≥60 years (r=0.71), Black race (r=0.85), lower health literacy (r=0.60), and lower educational attainment (r=0.63) (Table 3).

UNDERSTANDING AND CONCERNS OF KIDNEY TRANSPLANT COMPLICATIONS:

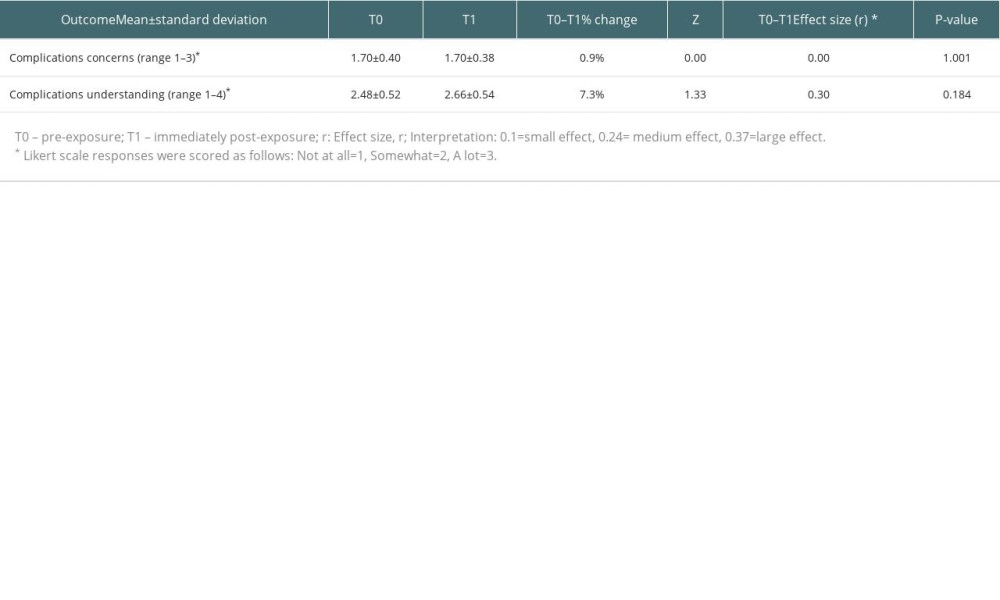

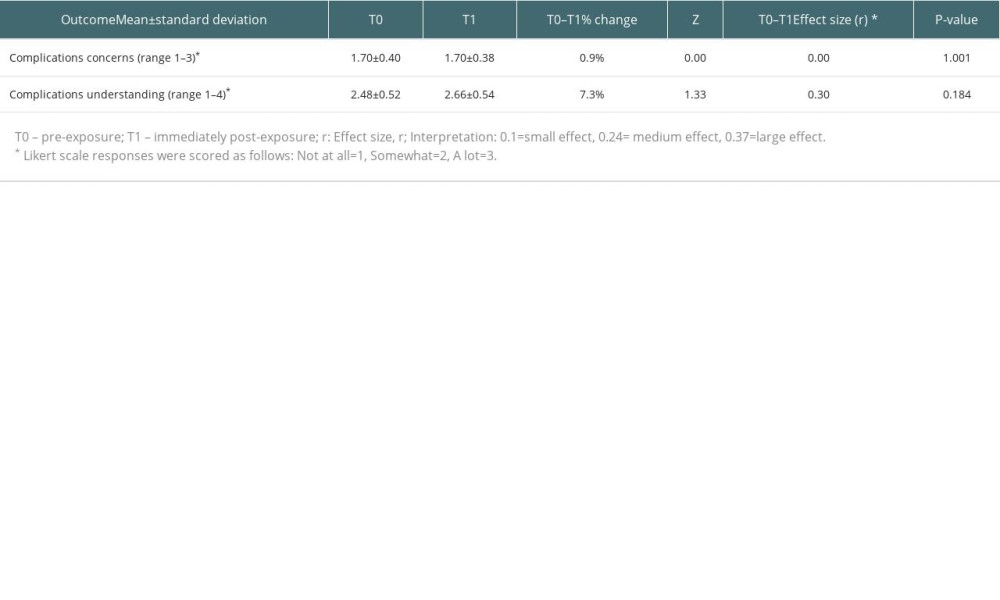

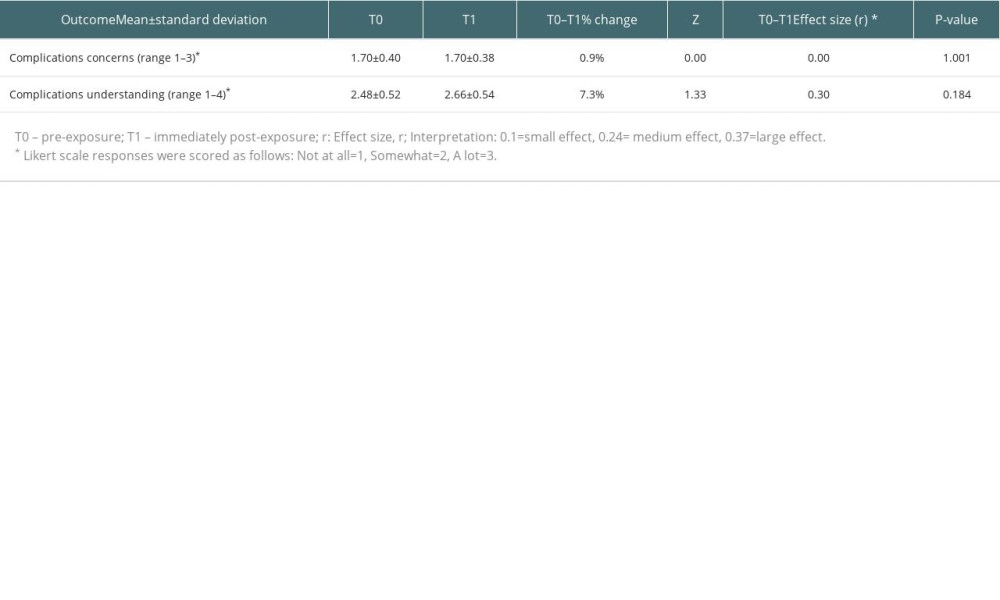

The mean total score for understanding kidney transplant complications increased after viewing by 7% (mean 2.48 to 2.66, P=0.184). The proportion of patients who reported understanding kidney transplant complications “a lot” increased from 41% before the videos to 64% after the videos. There was no change in mean concerns scores before and after video viewing (mean 1.70 to 1.70, P=1.00) (Table 4).

ACCEPTABILITY OF VIDEOS:

All patients reported agreement or strong agreement that the information in the videos was clear, credible, easy to understand, and helped them identify questions they wanted to ask. Also, all patients reported that they experienced the videos as acceptable to their culture and that they felt comfortable learning from similar videos, would use them in the future, and would recommend them to family and friends.

QUALITATIVE EVALUATION OF THE VIDEOS:

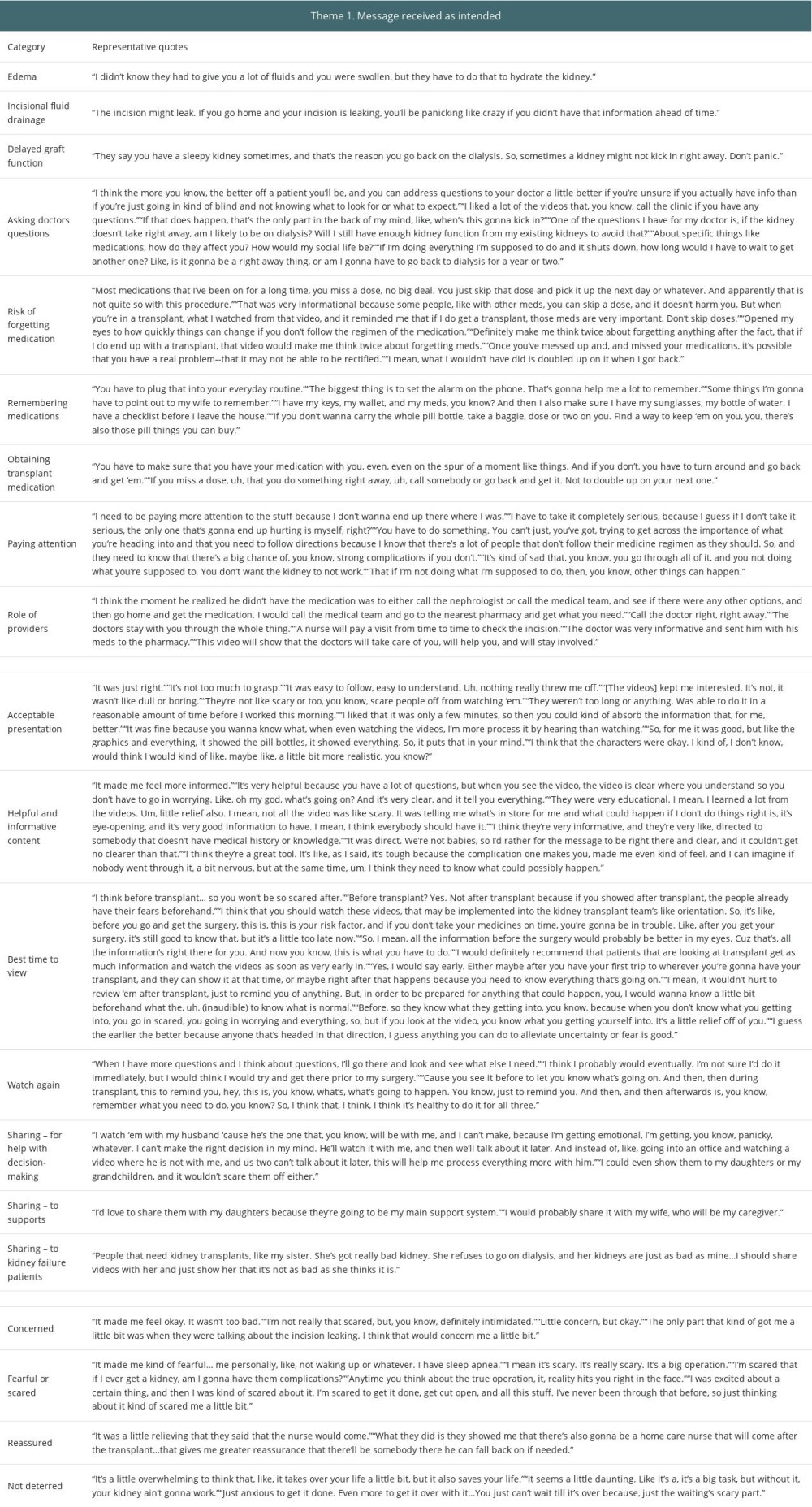

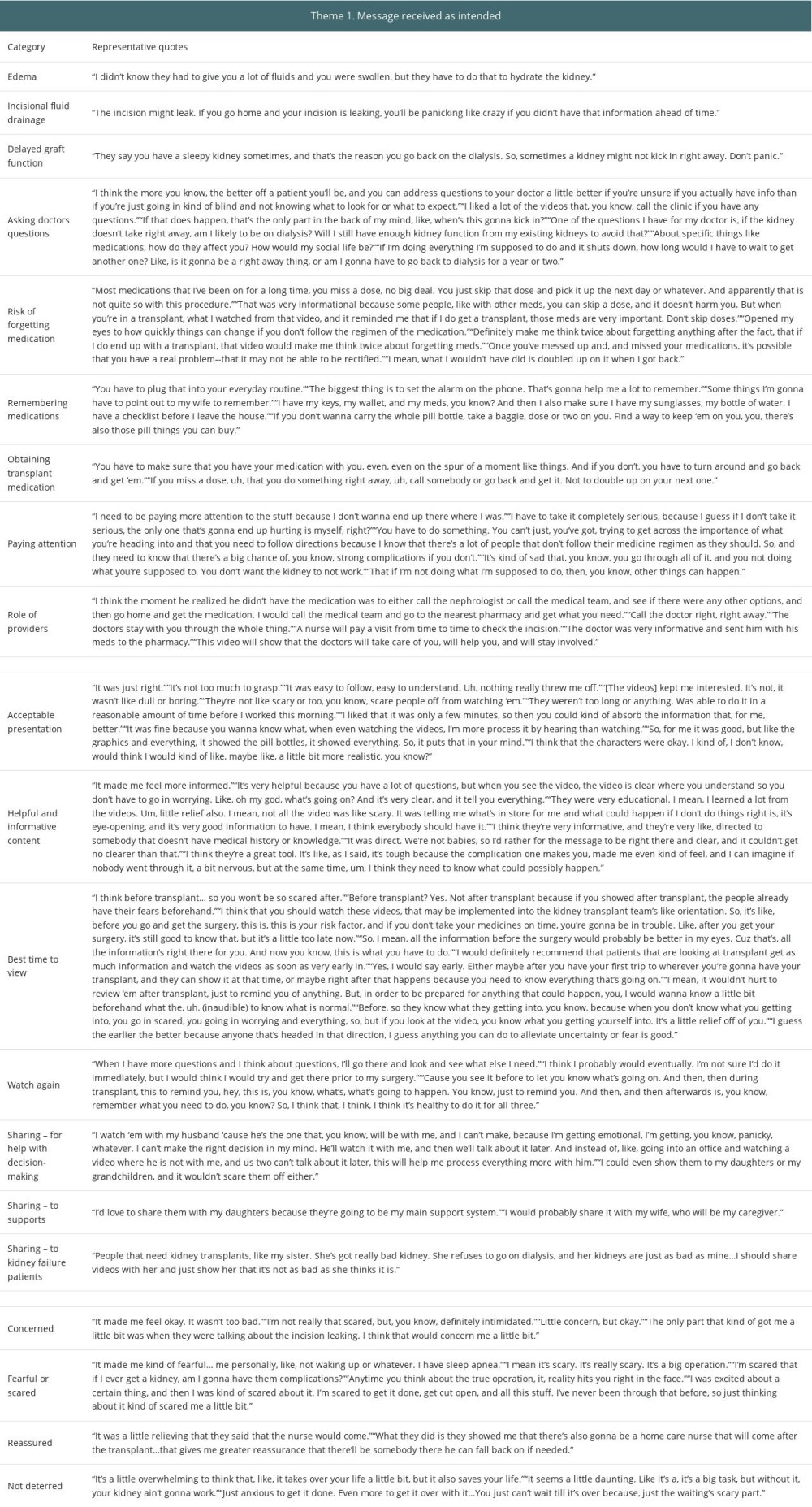

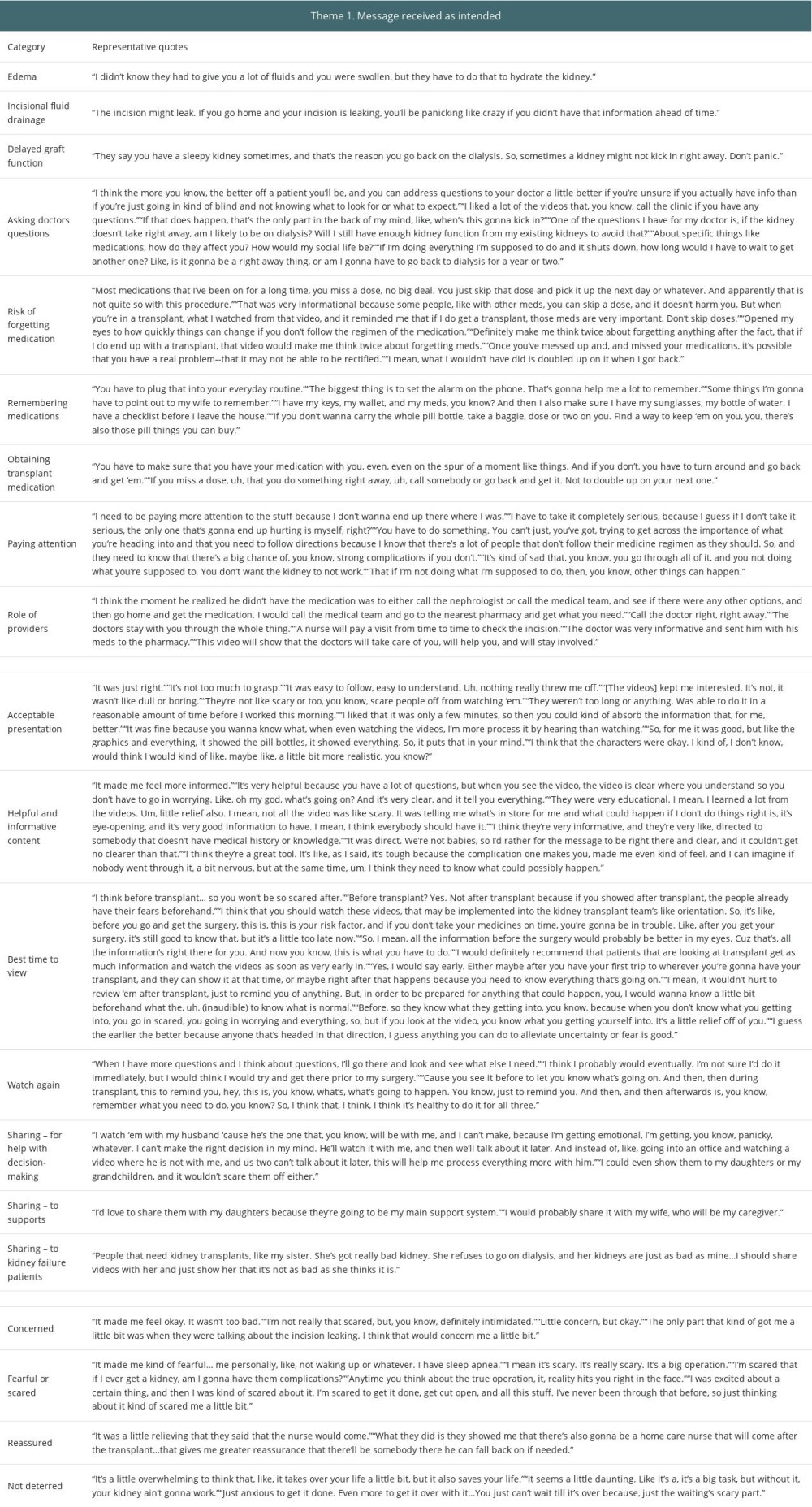

Of 12 patients who participated in the cognitive interviews to inform qualitative video evaluation, most were 50 years of age or older, and 58% were women. Most patients were non-Hispanic white, and 3 were African American. Half had annual household incomes under $30,000 and did not have college degrees. Interviews lasted between 13 and 44 min (average 27 min). Three themes of patient perceptions emerged: (1) messages received as intended, (2) felt informed, and (3) scared but not deterred. For each theme, categories and representative quotes are provided in Table 5 and are further described below.

THEME 1:

In response to questions about the content of the videos, patients indicated that nothing really surprised them, although there were a few things that they did not know. Many said that they had not realized they would receive a lot of fluids and could experience some swelling, that the kidney might not function right away, and that the incision could leak. Patients indicated that the information would help them talk to their doctors and ask questions. A few specified that they wanted some clarity on delayed kidney function, medication adverse effects, and failure of the transplanted kidney. A surprising element that was found was the risk of forgetting to take transplant medications. Patients gleaned that a routine is necessary and setting alarms or engaging caregivers can help. They picked up on or were reminded of some good strategies to help them remember, such as tying it to their own behaviors. They gave tips on how to remember the medications and agreed with “keeping it with you at all times”. Patients expressed the importance of obtaining the medicine after realizing it was forgotten by going back home or calling the doctor. They also expressed that it was not good to take a double dose of the medicine. Patients emphasized the importance of paying attention to make sure the kidney stays healthy. In general, the patients said that you must do what you have to do, or experience the consequences. Some referenced the role of providers and commented on the follow-up care they would receive.

THEME 2:

Patients deemed the presentation of the videos as acceptable. In terms of amount of information, patients reported “it was just right”, “just enough”, “not too much”, and “perfect”. Some went on to explain that they were expecting longer videos but that they were able to watch these before work, they were easy to absorb, and they absorbed more by hearing and watching. Patients also commented on the animated format. Most patients either did not mind or liked this format. Others were less enthusiastic but found the format acceptable. Regarding the content of both videos, patients found the content helpful, informative, direct, and compelling. Regarding when to watch the videos, nearly all patients said “before transplant” or “very early in”, with some suggesting it would be good to watch them as a refresher after the transplant. When asked if they would go back and watch other videos if they had access to them, most patients indicated that they would in order to answer their questions and to prepare prior to surgery. When asked whether they would or have shared the videos, patients either had or intended to do so. They gave a few main reasons for sharing: for help with decision-making, to inform support persons, and to inform patients with kidney failure.

THEME 3:

After watching the videos, many patients reported feeling overwhelmed or concerned. Several patients mentioned that they felt fearful or scared during the video or while thinking about transplantation. Some felt reassured, and the video prompted 1 patient to feel a sense of urgency or anxiousness to just get it all over with.

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

Our study findings should be interpreted with the following limitations. As a small pilot study in a single geographic location, with largely non-Hispanic white participants who consented to research, results may not generalize to other populations. The study was sufficiently powered to assess a large effect size rather than significance testing. The before-and-after study design tends to exaggerate effect sizes when compared to randomized trials. Although survey items for knowledge, understanding, and concerns were developed for the study, content validity was ensured through the involvement of kidney disease stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, a transplant surgeon, a dialysis social worker, and researchers in item generation and pilot testing; face validity was shown by their easy acceptance of the measure in our work. Our videos were not meant for informed consent but rather to improve individuals’ foundational knowledge of common kidney transplant complications to lower fear of the unknown and enhance understanding that can lead to self-efficacy in conversations with providers and seeking more information. The video health information on each topic was neither extensive nor comprehensive in covering every aspect of the disease entity, in order to prevent users from getting overwhelmed with too much information. We found that 5 complications within the 2 videos totaling 7 min was acceptable to maintain attentiveness without overwhelming learners or inducing extensive concern.

Conclusions

We evaluated 2 complementary educational animated videos about common kidney transplant complications, which were previously developed by our group in a human-centered design process. The results of our pilot study support the acceptability of the educational animations among kidney transplant patients at a single center and the feasibility in improving the knowledge and perception of understanding of common kidney transplant complications without worsening fears. Patient access to these videos, combined with other topics, can assist them in understanding information about transplantation and empower patients to discuss this further with transplant providers. Future research will evaluate the videos within the full KidneyTIME intervention to increase kidney transplant access. Educational interventions designed to enhance kidney transplant interest, decision-making, and preparation in the United States could increase the number of people pursuing kidney transplantation and access to the waitlist.

Tables

Table 1. Survey questions for kidney transplant complications knowledge, concerns, and understanding with item-wise summary statistics before and after viewing. Table 2. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 2. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. Table 3. Main and subgroup patient knowledge scores before and after video set viewing.

Table 3. Main and subgroup patient knowledge scores before and after video set viewing. Table 4. Kidney transplant complications concerns and understanding scores before and after video set viewing.

Table 4. Kidney transplant complications concerns and understanding scores before and after video set viewing. Table 5. Themes, categories, and representative quotes of patients.

Table 5. Themes, categories, and representative quotes of patients.

References

1. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Systematic review: Kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes: Am J Transplant, 2011; 11(10); 2093-109

2. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population: J Gen Intern Med, 2008; 23(5); 561-66

3. Lewis L, Dolph B, Said M, Feeley TH, Kayler LK, Enabling conversations: African American patients’ changing perceptions of kidney transplantation: J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 2019; 6(3); 536-45

4. Ranahan M, Von Visger J, Kayler LK, Describing barriers and facilitators for medication adherence and self-management among kidney transplant recipients using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model: Clin Transplant, 2020; 34(6); e13862

5. Alansari H, Almalki A, Sadagah L, Alharthi M, Hemodialysis patients’ willingness to undergo kidney transplantation: An observational study: Transplant Proc, 2017; 49(9); 2025-30

6. Biabani F, Rahmani A, MahmudiRad G, Reasons for kidney transplant refusal among patients receiving peritoneal dialysis: A qualitative study: Perit Dial Int, 2023; 43(5); 395-401

7. Nizič-Kos T, Ponikvar A, Buturović-Ponikvar J, Reasons for refusing kidney transplantation among chronic dialysis patients: Ther Apher Dial, 2013; 17(4); 419-24

8. Gordon EJ, Patients’ decisions for treatment of end-stage renal disease and their implications for access to transplantation: Soc Sci Med, 2001; 53(8); 971-87

9. Kazley AS, Simpson KN, Chavin KD, Baliga P, Barriers facing patients referred for kidney transplant cause loss to follow-up: Kidney Int, 2012; 82(9); 1018-23

10. Matas AJ, Schnitzler M, Payment for living donor (vendor) kidneys: A cost-effectiveness analysis: Am J Transplant, 2004; 4(2); 216-21

11. Adams K, Greiner AC: 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A focus on communities, 2004, Washington, DC, National Academies Press

12. Rivet Amico K, A situated-Information Motivation Behavioral Skills Model of Care Initiation and Maintenance (sIMB-CIM): An IMB model based approach to understanding and intervening in engagement in care for chronic medical conditions: J Health Psychol, 2011; 16(7); 1071-81

13. Trivedi P, Rosaasen N, Mansell H, The health-care provider’s perspective of education before kidney transplantation: Prog Transplant, 2016; 26(4); 322-27

14. Rosaasen N, Mainra R, Shoker A, Education before kidney transplantation: Prog Transplant, 2017; 27(1); 58-64

15. Pullano T, Solbu A, Cadzow R, Interviews with lay caregivers about their experiences supporting patients throughout kidney transplantation: Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Science Community Research Day, 2023, Buffalo, NY

16. Cossart AR, Staatz CE, Campbell SB, Investigating barriers to immunosuppressant medication adherence in renal transplant patients: Nephrology (Carlton), 2019; 24(1); 102-10 Erratum in: Nephrology (Carlton). 2020;25(2):189

17. Andersen MH, Urstad KH, Larsen MH, Intervening on health literacy by knowledge translation processes in kidney transplantation: A feasibility study: J Ren Care, 2022; 48(1); 60-68

18. Morinelli TA, Taber DJ, Su Z, A dialysis center educational video intervention increases patient self-efficacy and kidney transplant evaluations: Prog Transplant, 2022; 32(1); 27-34

19. Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Cui Y, Your path to transplant: A randomized controlled trial of a tailored expert system intervention to increase knowledge, attitudes, and pursuit of kidney transplant: Am J Transplant, 2021; 21(3); 1186-96

20. Lorenz EC, Petterson TM, Schinstock CA, The relationship between health literacy and outcomes before and after kidney transplantation: Transplant Direct, 2022; 8(10); e1377

21. Boonstra MD, Reijneveld SA, Foitzik EM, How to tackle health literacy problems in chronic kidney disease patients? A systematic review to identify promising intervention targets and strategies: Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2020; 36(7); 1207-21

22. Kayler LK, Majumder M, Dolph B, Development and preliminary evaluation of IRD-1-2-3: an animated video to inform transplant candidates about increased risk donor kidneys: Transplantation, 2020; 104(2); 326-34

23. Kim S, Ju MK, Son S, Development of video-based educational materials for kidney-transplant patients: PLoS One, 2020; 15(8); e0236750

24. Tou S, Tou W, Mah D, Effect of preoperative two-dimensional animation information on perioperative anxiety and knowledge retention in patients undergoing bowel surgery: A randomized pilot study: Colorectal Dis, 2013; 15(5); e256-65

25. Yap J, Teo TY, Foong P, A randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of a portable patient education video prior to coronary angiography and angioplasty: Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2020; 96(7); 1409-14

26. Eggeling M, Bientzle M, Shiozawa T, The impact of visualization format and navigational options on laypeople’s perception and preference of surgery information videos: randomized controlled trial and online survey: J Particip Med, 2018; 10(4); e12338

27. Kayler LK, Dolph B, Seibert R, Development of the living donation and kidney transplantation information made easy (KidneyTIME) educational animations: Clin Transplant, 2020; 34(4); e13830

28. Kayler LK, Keller MM, Breckenridge B, Preliminary feasibility of animated video education designed to empower patients’ referral to kidney transplantation: Clin Transplant, 2023; 37(1); e14838

29. Traino HM, Nonterah CW, Gupta G, Mincemoyer J, Living kidney donors’ information needs and preferences: Prog Transplant, 2016; 26(1); 47-54

30. Reigeluth CM, In search of a better way to organize instruction: The elaboration theory: J Instr Dev, 1979; 2(3); 8-15

31. Mayer RE, Moreno R, Animation as an aid to multimedia learning: Educ Psych Rev, 2002; 14(1); 87-99

32. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ, Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation: J Exp Psychol Gen, 2012; 141(1); 2-18 Erratum in: J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141(1):30

33. Leiner M, Handal G, Williams D, Patient communication: A multidisciplinary approach using animated cartoons: Health Educ Res, 2004; 19(5); 591-95

34. Slater M, Rouner D, Entertainment education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion: Commun Theory, 2002; 12(2); 173-91

35. Gagliano ME, A literature review on the efficacy of video in patient education: J Med Educ, 1988; 63(10); 785-92

36. Smeda N, Dakich E, Sharda N, The effectiveness of digital storytelling in the classrooms: A comprehensive study: Smart Learn Environ, 2014; 1(1); 6

Tables

Table 1. Survey questions for kidney transplant complications knowledge, concerns, and understanding with item-wise summary statistics before and after viewing.

Table 1. Survey questions for kidney transplant complications knowledge, concerns, and understanding with item-wise summary statistics before and after viewing. Table 2. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 2. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. Table 3. Main and subgroup patient knowledge scores before and after video set viewing.

Table 3. Main and subgroup patient knowledge scores before and after video set viewing. Table 4. Kidney transplant complications concerns and understanding scores before and after video set viewing.

Table 4. Kidney transplant complications concerns and understanding scores before and after video set viewing. Table 5. Themes, categories, and representative quotes of patients.

Table 5. Themes, categories, and representative quotes of patients. Table 1. Survey questions for kidney transplant complications knowledge, concerns, and understanding with item-wise summary statistics before and after viewing.

Table 1. Survey questions for kidney transplant complications knowledge, concerns, and understanding with item-wise summary statistics before and after viewing. Table 2. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 2. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. Table 3. Main and subgroup patient knowledge scores before and after video set viewing.

Table 3. Main and subgroup patient knowledge scores before and after video set viewing. Table 4. Kidney transplant complications concerns and understanding scores before and after video set viewing.

Table 4. Kidney transplant complications concerns and understanding scores before and after video set viewing. Table 5. Themes, categories, and representative quotes of patients.

Table 5. Themes, categories, and representative quotes of patients. In Press

18 Mar 2024 : Original article

Does Antibiotic Use Increase the Risk of Post-Transplantation Diabetes Mellitus? A Retrospective Study of R...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943282

20 Mar 2024 : Original article

Transplant Nephrectomy: A Comparative Study of Timing and Techniques in a Single InstitutionAnn Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942252

28 Mar 2024 : Original article

Association Between FEV₁ Decline Rate and Mortality in Long-Term Follow-Up of a 21-Patient Pilot Clinical T...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.942823

02 Apr 2024 : Original article

Liver Transplantation from Brain-Dead Donors with Hepatitis B or C in South Korea: A 2014-2020 Korean Organ...Ann Transplant In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AOT.943588

Most Viewed Current Articles

05 Apr 2022 : Original article

Impact of Statins on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Living-Donor Liver TransplantationDOI :10.12659/AOT.935604

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935604

12 Jan 2022 : Original article

Risk Factors for Developing BK Virus-Associated Nephropathy: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study of ...DOI :10.12659/AOT.934738

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e934738

22 Nov 2022 : Original article

Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipient...DOI :10.12659/AOT.937988

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e937988

15 Mar 2022 : Case report

Combined Liver, Pancreas-Duodenum, and Kidney Transplantation for Patients with Hepatitis B Cirrhosis, Urem...DOI :10.12659/AOT.935860

Ann Transplant 2022; 27:e935860